With Minimum Touch Orthodontics, John Graham, DDS, MD, has a treatment workflow that meets the needs of the “customer”

By Alison Werner | Photography by Aynn Ford Photography

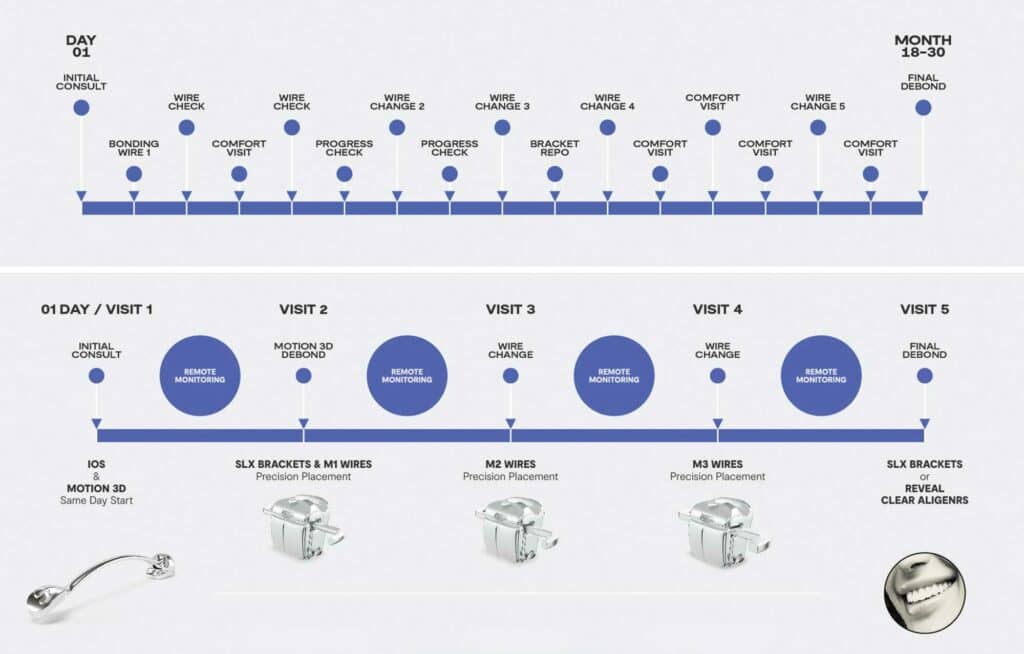

As Henry Schein Orthodontics (HSO) illustrates it (see Figure 1), the conventional orthodontic patient journey entails progress checks, wire changes, bracket repositioning, and comfort appointments after initial bracket bonding. And over the course of treatment, which can last anywhere from 18 to 30 months, it’s not unheard of for the patient to make the trek into the orthodontic office 16 to 20 times between initial consult and final debond. While the conventional wisdom is that all these touch points are proof of good orthodontic customer service, orthodontist John Graham, DDS, MD, begs to differ, and so does HSO.

Of late, the company has placed an emphasis on Minimum Touch Orthodontics. The premise being that with the right appliances and new technology, orthodontic treatment does not need to so infringe on patients’ valuable time. And, given the pandemic, this approach is timely given the need to minimize in-person visits with social distancing requirements. HSO’s Minimum Touch Orthodontics workflow brings together three of the company’s key product offerings: the Carriere Motion 3D Appliance, the SLX 3D Clear and Metal Bracket System, and the M-Series Wires System. When coupled with remote monitoring technology, the patient journey is significantly transformed.

As Graham, who is an advisor and lecturer for HSO, puts it, the Motion 3D appliance is the workhorse of the workflow and really makes all the difference in the ability of the orthodontist to move the patient through treatment at a quicker pace—anywhere from 11 to 16 months under the Minimum Touch Orthodontics workflow. With the Sagittal First Philosophy, promoted by HSO, in mind, the Motion 3D appliance is used to reclassify Class II/III cases into Class I at the beginning of treatment. Once the Class I environment is achieved, patients can then finish with braces or aligners within a shortened overall treatment time.

Graham’s protocol calls for an aligner/retainer as part of the Motion stage to help anchor the two molars that otherwise could roll out laterally. Using the Motion appliance, Graham typically finishes Class II/III correction within 3½ to 4 months—compared to the conventional workflow where the same correction, working through archwires and elastics, can take over a year.

One advantage of completing Class II/III correction at the start is that patients are still gung-ho about treatment and more willing to be compliant with elastics.

“The conventional approach to AP correction is kind of a dirty trick we play on our patients,” says Graham. “A year into treatment, when they’re starting to not like us very much, we say, ‘Hey, guess what? Now I’m going to add a layer of complexity to your treatment and if we’re not done when I told you it’s because you’re not doing the work.’ It’s really unfair because we’re catching them when they’re exhausted and burnt out.”

Once a Class I occlusion is achieved, the Motion 3D appliance is debonded and SLX brackets and the M-Series wires are placed. Looking at the Minimum Touch Orthodontics workflow illustrated in Figure 1 above, HSO approximates placement at 24 weeks, with wire changes at approximately 28 and 37 weeks. Of course, individual cases may vary. These bracket and wire systems have been designed to allow for precision placement, along with reducing the number of wire changes and bracket repositioning.

This system translates to fewer overall appointments—or touch points. In the Minimum Touch workflow, as shown in Figure 1, patients may need only come into the office four to six times over the course of treatment—and that includes initial consult and same day start with the Motion 3D appliance and final debond. As Graham sees it, reducing the number of overall touch points is extremely valuable in creating a good patient experience. “If you have corrected the Class II or Class III in the very first few months of treatment, that is a lot of time that you’ve taken out of the treatment length which is a lot of opportunity for brackets to break and appliances to fail—all of which create more touch points,” he says from his Salt Lake City office which exudes a minimalist aesthetic. What’s more, those extra touch points are neither good for the practice financially nor for the patient experience. You don’t want the patient to leave your office thinking: Yeah, Dr X was great. The practice was nice. But my gosh, I was there all the time!

What makes shortened treatment time and fewer in-person office visits possible—all while still providing a beautiful outcome—is the reported precision of the appliances and remote monitoring technology.

Remote monitoring technology has advanced steadily over the last few years, and there are several options on the market now, including Dental Monitoring, Grin, SmileSnap, etc. Graham first adopted the technology 5 years ago, opting for Dental Monitoring, but it was only in the last 3 months that he finally went all in.

“Every single patient now is on Dental Monitoring,” says Graham, who is an investor in the company. “No patients are going to have regularly scheduled ortho appointments. Those appointments will be determined by me and my staff when the time is right, based upon what we’re seeing on our Dental Monitoring dashboard.” And that dashboard allows the practice to monitor tooth movement, velocity, aligner fit, how wires and brackets are functioning, including whether a NiTi wire is fully expressed, and check for broken appliances a patient might not recognize. In addition, Dental Monitoring allows Graham to observe the visible development of caries, gingival recession, and very importantly, oral hygiene. At the heart of this is a commitment from Graham to be respectful of his patients’ time.

But tied into it is Graham’s position that the evidence supporting appointments for bracket patients at 4- to 6-week intervals in conventional treatment is non-existent. “There’s zero science behind our appointment scheduling recommendations, and there never has been. It’s always been about scheduling. That’s not science. We don’t know what it’s going to look like in 4 to 6 weeks. We can guess, but we don’t know,” he points out. Under his new protocol, and using the HSO Minimum Touch Orthodontics workflow, a patient can go months between in-person appointments, and it’s the technology, as Graham sees it, that makes this possible. “I can observe clinical findings on a far more granular level and far sooner with Dental Monitoring than I ever have just with my own eyes,” he says.

Patient response has been extremely positive, according to Graham. “I can’t tell you how thrilled patients are. At first, we thought patients would resist remote monitoring. We were under the false assumption that patients would think we weren’t being touchy enough, wondering if we were even looking at them, but that’s not how patients perceive it. First, they recognize the artificial intelligence and machine learning technology and they’re interested in it. But they also appreciate the fact that we respect their time enough to not have them come in only to say: ‘Everything looks great. I’ll see you again in 4 weeks.’”

This isn’t the first time Graham has excised what he calls “wasted and superfluous visits.” In 2009, he stopped doing retainer checks. “At first you may think, ‘Well, geez, that’s irresponsible.’ But it’s interesting when you start thinking about it: There are no other specialties in medicine or dentistry that do something equivalent of a retainer check, not even close,” he says.

As Graham, who switched to a career in orthodontics after initially training in surgery, points out, a patient who has paid $60,000 to $120,000 for a full mouth reconstruction isn’t asked to go back to their prosthodontist in 3 months for a margin check on all their restorations. A patient doesn’t go back to the cardiothoracic surgeon every 3 months after a valve replacement—at most they’re going in once a year for an echocardiogram. Orthodontists meanwhile schedule patients for retainer checks, where more often than not, the doctor response is: Everything is working perfectly. The retainer fits beautifully. Meanwhile, the parent who pulled their kid out of school and took time off work is asking themselves: You mean we came in here for that?

“Orthodontists have somehow been convinced into thinking that they have a fiduciary responsibility to baby-sit their patients until the end of time,” says Graham, who provides retainer replacements at no cost for life. “And the crazy thing is: Patients don’t want to keep coming back! They know where your office is. They know who you are. They know your phone number. They also know that if they call because their retainer doesn’t fit you are going to have them come in. Since 2009, I haven’t had a single patient call and say, ‘I’m frustrated because you’re not doing retainer checks.’”

Graham acknowledges that there are those practices that use these appointments to maintain a relationship with siblings—but that’s a business/marketing decision. “If that’s the way you want to use it, that’s great. But as I see it, from a doctor-patient perspective, there is no good reason for it.”

What Graham is asking orthodontists to do is to shift their way of thinking. This isn’t about providing the bare minimum. It’s about respecting the patient’s time and leaning into the technology that is available. And, given the pandemic, it’s reducing unnecessary touch points.

“Every time I have a patient sit in a chair it’s over $200 cost to me—whether they sit there for 5 minutes or an hour and a half, based on fixed costs. If I have a bunch of extra appointments, that I don’t need, that’s just wasteful—and it’s not making the patient’s outcome any better. My care for them isn’t any better just because they’re showing up for an extra 10 to 20 appointments.”

As is abundantly clear, the heart of Graham’s treatment philosophy is a respect for the patient’s time. And this ties into recognizing that the patient isn’t just a patient. They are a consumer and a customer.

Graham uses an interesting example to illustrate his point. “If an emergency room can consider their patients customers by putting billboards up in cities saying, ‘Our wait time is 2 minutes,’ then clearly we can get over our arrogance as practitioners in the specialty of orthodontics and look at these patients for what they are: customers.”

During his new patient consults, Graham is direct, “I say, ‘In my eyes, clearly, you’re a patient, but even more importantly, you’re a customer.’ What that means is customer satisfaction is paramount.” So, if a patient wants to end treatment halfway through because they are tired, but are happy with where they are, and there is no demonstrable risk of dental or joint harm in doing so, then that’s the customer’s decision. If a patient doesn’t want to wear elastics because they don’t care about their Class II correction, then that’s fine, as long as they understand his reasons for wishing to continue, and that it’s well documented that it was their well-informed decision. “I’m here to serve at the pleasure of my patients/customers. As long as they leave my office feeling better than they did when they came in, meaning feeling better about themselves or about the way they experienced treatment with me, then I think that’s a recipe for success.” And that approach is clearly working. Customers are seeking him out, as new patient consultations, while not ideal, are booking at 12 weeks out at his practice.

In Graham’s view nothing has done more to change his mind set about the patient as customer than the growth of direct-to-consumer (DTC) clear aligner companies. Graham isn’t nearly as wary of the DTC segment as most. He recognizes that these companies can serve a certain subset of patients, but what’s more, he recognizes that their DTC marketing campaigns are doing much to raise consumer awareness about orthodontic treatment overall—much as Invisalign did in the early 2000s.

“I think many other orthodontists have [noticed this] as well. We’ve noticed an increase in the number of patients who are just cold calling us, and I think it’s because they’re just aware—and I think it’s great,” says Graham who is also seeing an increasing number of dissatisfied DTC customers seek him out for treatment to correct problems with their occlusion that they feel did not exist prior to their DTC orthodontic treatment.

But the impact of DTC marketing goes a step further. It has been key to influencing the way Graham speaks to prospective patients and how he views his “patients.”

“Like I previously mentioned, I have evolved to the point where I really see my patients equally as customers and patients,” he says. “This is discretionary income we’re talking about. No one has ever died from a malocclusion, as far as I’m aware. They don’t usually come to see you in pain. Many of our patients are fine, and many of our patients will remain fine without orthodontic treatment. So, for individuals that are in that category of consultations, they are primarily customers.”

The fact is that the patient-as-customer has two key pain points: money and time. In the orthodontic world, the technology is now there to really account for one of those: the customer’s time. OP

Alison Werner if chief editor of Orthodontic Products.