Part 1: Recognizing and controlling destructive habits

Part 1: Recognizing and controlling destructive habits

by Michael C. Alpern, DDS, MS

Orthodontists are humans treating humans. Since humans are not perfect, periodically, the biomechanical treatment plan we have for a patient can go off-plan. Thirty-five years of clinical practice, teaching, and taking CE courses has led me to the following potential solutions.

Recognize the Problem

The first thing the great teachers who taught me stressed is to recognize when there is a problem as soon as possible. You may not know the answer to the problem (yet), but you can see that treatment is not headed toward the solution you initially planned.

Stop All Active Treatment

The next step is to remove the existing archwires, stop all elastics, and see the patient again in about 2 to 4 weeks. At that appointment, your goal is to find the core of the problem.

Rediagnose the Patient and Take New Records

For me, this involves making a complete set of records including, but not limited to, complete intraoral and facial photographs, models of the teeth in current maximum interdigitation, a lateral cephalometric radiograph, and a panoramic radiograph. (I digitize all lateral cephalometric images.) I look at where I started and where I am now. I ask myself the following questions: 1) What effect did growth have? 2) Where did the incisors and molars move to? 3) Was this tooth movement what I had planned?

Rediagnosis also involves thoroughly reading the patient’s chart to see what role the patient may have played in his or her treatment. This includes attendance at or absences from appointments, cooperation with hygiene, full-time elastic wear, and destructive habits. I am not looking for blame, but merely trying to search for what needs to change in order to achieve a successful, attractive, functional smile for the patient.

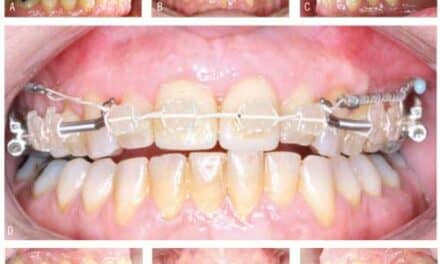

This image of a transfer patient shows the upper and lower teeth in occlusion. The midlines are off, and an open bite appears from the cuspids to the molars. The cuspids show bone and gingival loss.

This image of a transfer patient shows the upper and lower teeth in occlusion. The midlines are off, and an open bite appears from the cuspids to the molars. The cuspids show bone and gingival loss.

Reconsult with the Patient and/or Parents

This involves showing the patient and/or parents where we started, where we are now, and what needs to change to achieve success. I find that a 25-inch flat-screen HD monitor is very helpful in allowing everyone to see where we began treatment and what my concerns are regarding the treatment progress. This type of screen can visually zoom in on gingival infections, remaining malocclusions, and tongue thrusts, effectively highlighting where we need to make changes to the existing doctor/patient/parent relationship.

My approach is not a “blame game.” Instead, my goal is to communicate that, “This is what the remaining challenges are, and here are the solutions.” I show all initial and current photos and comparisons. Digital, adjunctive graphic programs assist in my communication with the patient and/or parents.

Once the biomechanical challenges have been visualized, I have a frank discussion with the patient and parents, beginning with a questions such as, “How do you feel, now that you see what we have accomplished so far? Are you comfortable enough to cooperate and to help me help you to achieve this winning smile that you and your parents want for you?”

In difficult situations, sometimes I remind the patient that, “Quitting is easy, but that would not help you feel better about your appearance; and it would potentially waste the financial sacrifice your family is making so you will improve your appearance.”

My common theme is, “I am worried and concerned about …” I repeat this enough to make sure we stay on track for successfully finding solutions. Most importantly, I present a clear program that will achieve these solutions. I don’t say, “You are leaving too much food around your teeth, gums, and braces, causing infection which stops effective tooth movement.” Instead, I try to help both the patient and the parents with printed, step-by-step instructions, photographs, and the offer for us to see the patient and parents weekly in order to achieve the result.

The lateral cephalometric image of the same patient shows a marked vertical pattern with an open bite between the molars and the incisors.

The lateral cephalometric image of the same patient shows a marked vertical pattern with an open bite between the molars and the incisors.

The lateral cephalometric image of the same patient shows a marked vertical pattern with an open bite between the molars and the incisors.

The potential results of this conference include: 1) The patient and parents agree to do their part to complete treatment. 2) The patient and parents are indecisive, in which case we schedule a second consult in 1 week. 3) The patient and parents have given up and want treatment to stop.

At this point, Informed Consent is required for all parties to teach them the risks to stopping treatment before completion. This is presented orally twice, and everyone signs agreements (with copies sent to the general dentist). One copy goes in their file, and another signed copy gets mailed home. Most importantly, the patient and the parents sign the treatment chart, verifying everything that they have been told and their decision to accept all consequences.

This entire process of encountering a problem, rediagnosing the problem, and presenting a new consultation is also clearly discussed twice in my original Informed Consent agreement. This includes a document that is initialed by the patients and parents as well as a follow-up letter.

During the reconsult, I try to present enough clear, visual evidence for the patient and parents to understand. I want them to know that, as their orthodontist, I have recognized an important problem, taken very thorough records, and spent a lot of time finding what needs to change to achieve success.

This is the first in a series of articles about troubleshooting orthodontic treatment problems. We begin with controlling destructive habits.

Controlling Destructive Habits

In the past 20 years, I have become more aware of unintentional habits that many patients, regardless of age, may have and which can interfere with or prevent corrective orthodontic biomechanics. My study of destructive habits began with my attention to the TMJ, TMD, and TMJ DJD problems presented by more than 50% to 75% of my orthodontic patients at their initial orthodontic examination. Many of the most destructive habits presented by patients can significantly affect the TMJs, and can also reduce any chance of successful orthodontic treatment. These habits include the following:

1) Leaning and sleeping on the mandible, face, or neck. In nearly 44 years of diagnosing and treating patients with TMJ symptoms, I have found that nearly all of these patients leaned on their jaw, face, or neck in the reception room and initial examination room. If the combined weight of the head, neck, and shoulders is potentially 15 to 30 pounds, imagine the kind of pressure this posture applies to the mandible, face, and neck. If a patient uses his hands as “orthopaedic posts” to lean on, the result would be huge forces affecting facial growth centers and fragile TMJ fibrocartilage that cannot tolerate loading. Orthopaedic forces can also cause marked facial asymmetry and must be stopped before the beginning of the circumpubertal growth spurt.

The panoramic radiograph appears to show left TMJ degenerative joint disease. There also appears to be generalized bone loss. The cone beam CT scan (to come later) showed more severe bone loss on all of the upper teeth and many of the mandibular teeth.

The panoramic radiograph appears to show left TMJ degenerative joint disease. There also appears to be generalized bone loss. The cone beam CT scan (to come later) showed more severe bone loss on all of the upper teeth and many of the mandibular teeth.Consider a skeletal and dental Class II patient who is wearing 6-ounce, Class II elastics to move mandibular teeth forward and maxillary teeth slightly posteriorly. At the same time, the mandibular teeth, the mandible, and the TMJ fibrocartilage are receiving opposing forces of 20 pounds of posterior-medial pressure on the side receiving the direct force in addition to the resulting abnormal lateral pressures on the contralateral side. These pressures can continue for long periods of time each day and night. This is no contest. The 6-ounce orthodontic elastics’ forces are insignificant and fail to achieve correction, regardless of whether a cooperative patient wears them full-time as directed. The parents may swear that the patient is compliant, and all of them will get frustrated with the orthodontist saying there is no effective tooth movement. All because they don’t know about the opposing destructive forces that prevent orthodontic correction.

It’s not just the 20 to 30 pounds of force, it’s also the time factor. Teenagers go to school and lean on their jaws for 3 to 6 hours per day. At home, they sit watching television or at their computers, with one hand on the remote or the mouse and the other hand leaning on their jaw—for hours. Worse, these patients sleep on their stomachs or sides. In either case, significant sleeping time is spent with destructive habits loading bone growth centers and preventing effective tooth movement.

2) Simultaneously, many of these same patients bite their fingernails; chew gum; or chew on ice, pencils, pens, and other objects. These habits place huge forces on teeth and can break appliances and teeth. I have observed skeletal and dental Class II patients (in active orthodontic treatment) whose overjet has actually increased during several months of Class II elastic therapy.

Patients who bite their fingernails are constantly breaking bonded brackets, bending archwires, and fracturing enamel surfaces. These same patients can cause multiple fractures in TMJ fibrocartilage which has no blood supply and cannot heal.

I immediately referred this patient to a periodontist. The results of his complete examination dramatically altered any future orthodontic treatment. However, this is an example of why progress photographs and radiographs are critically important for all patients, especially those in which treatment may not be following the original treatment plan. The image at top left is the maxillary arch, and the image at top right is the mandibular arch. The maxillary arch is constricted with extraction of the first bicuspids. The mandibular arch is wider than the maxillary arch. The opposite should be true. The side views of the occlusion show marked bone and gingival loss to the bicuspids and molars.

I immediately referred this patient to a periodontist. The results of his complete examination dramatically altered any future orthodontic treatment. However, this is an example of why progress photographs and radiographs are critically important for all patients, especially those in which treatment may not be following the original treatment plan. The image at top left is the maxillary arch, and the image at top right is the mandibular arch. The maxillary arch is constricted with extraction of the first bicuspids. The mandibular arch is wider than the maxillary arch. The opposite should be true. The side views of the occlusion show marked bone and gingival loss to the bicuspids and molars.Psychological Treatment

Clinical psychologists view the correction of these types of destructive habits as “lifestyle changes.” Orthodontists are not trained (to the same degree) as clinical psychologists are in attempting to correct these habits. For 30 years, I routinely referred TMJ symptomatic patients to a PhD clinical psychologist. The result was a substantial diminishing of TMJ symptoms.

As orthodontists, we might consider finding the right PhD clinical neurophysiologist willing to work with our patients to change these habits. This usually does not require long-term psychological treatment. Many times, only four to six appointments (followed by periodic “tune-ups”) are required.

I have also found it rewarding to have this same psychologist educate me and my entire team. This enables us to assist in the follow-up of stopping destructive habits and motivating the patient to cooperate.

An additional consideration is that today’s orthodontic patients are often dealing with divorced or dysfunctional family situations, bullying at schools, and many other stressful components that can interfere with their cooperation. Many times, the psychologist recognizes these problems and can help.

Physical Treatment

We have also developed a series of steps to help stop destructive habits. These include the following:

1) We ask parents to buy inexpensive tennis balls. Whenever patients are home, they must constantly hold the tennis balls in their hands. They can toss them, bounce them, and squeeze them. You cannot lean on your jaw or bite your fingernails while constantly holding tennis balls. This technique can also have the positive effect of improving hand-eye coordination and increasing hand strength for sports or self-defense.

2) We also ask parents to buy dog-bone-shaped “contour pillows” for neck support during sleeping. We advise taking the large pillow they used to place behind the patient’s neck and instead placing the original pillow under their knees. Many patients are uncomfortable sleeping on their backs. Using the comfort pillow under their neck and the large pillow under their knees simulates a contour bed and offers comfort.

This works until the patient enters REM sleep. Then, destructive habits return and patients roll over onto their jaws. Our solution is inexpensive, no-risk, and very effective. We have parents purchase at least six more tennis balls, a slightly small, lycra exercise shirt, and diaper-type safety pins. We tell them to place six tennis balls in six cotton socks, which are safety-pinned to the shirt, one set above and two below the trans-nipple line and 10 to 12 inches apart. This combination is very light and easy to get used to. And as soon as the patient begins to roll into a destructive-habit position, the tennis balls in socks make him uncomfortable but does not wake him up—and the patient learns to sleep on his back.

Retrospectively, we have found it important to present this information during the consultation, at the same time I offer a diagnosis and informed consent. In this manner, when the problem arises during treatment, the suggested solutions are not a surprise to patients or parents.

Follow-up articles will continue this discussion of destructive habit control training, as well as other key solutions to redirecting a potentially failing treatment plan.

Michael C. Alpern, DDS, MS, maintains a private practice in Port Charlotte, Fla. He can be reached at [email protected].

Part 1: Recognizing and controlling destructive habits

Part 1: Recognizing and controlling destructive habits