Pobanz

Treating Palatally Impacted Canines with TOMAS

John M. Pobanz, DDS, MS, Diplomate, ABO

South Ogden, Utah

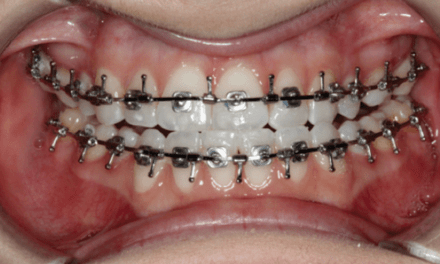

Efficient clinical management of palatally impacted canines is truly one of the most challenging orthodontic problems that clinicians face. Traditionally, a full fixed appliance worked to a full-dimension stainless steel wire serves as the anchorage unit to apply vertical and lateral force vectors to the impacted tooth. Depending upon the original position of the impacted canine, it can be difficult to avoid a collision of the crown of the impacted canine with the adjacent roots of the central and lateral incisors during force eruption.

Alternatively, indirect anchorage can be created with a 6-mm TOMAS anchorage pin strategically placed on the palatal aspect between a second bicuspid and a first permanent molar. This is a favorable location for insertion because of the generous bone adjacent to the single palatal root of the first molar. A TOMAS system T-bar, engaging the anchorage pin cross-slot and secured with composite with its horizontal extensions bonded to the lingual of each adjacent tooth, completes the indirect anchorage unit.

A self-ligating bracket, bonded to the lingual of the second bicuspid but occlusal to the horizontal extension of the T-Bar, serves as an easy-to-manage insertion point for a .021 x .025 Beta-Titanium eruption cantilever arm. This arm can be customized to deliver distal, vertical, and lateral force vectors as determined by 3D CBCT evaluation of the original position of the canine relative to the roots of the adjacent teeth. The rate-limiting step of such cases—vertical eruption of the impacted tooth—can be addressed immediately at the beginning of treatment, coupled with a thorough exposure of the entire anatomical crown and luxation prior to force application to a bonded attachment. With this approach, it is not uncommon to observe an emergence of the impacted tooth through the palatal tissue and away from the roots of the adjacent teeth within the first 4 months of force application.

Full fixed appliance placement follows, with traditional methods to guide the canine to its appropriate place in the arch. Patients should enjoy a significantly reduced treatment time spent in full fixed appliances, while clinicians will see a significant reduction in the number of office visits required to deliver care.

Goodman

The Excellent Torquing Spring

Phillip M. Goodman, DDS, MSc, PhD

Dayton, Ohio

One of the most challenging issues we as orthodontic practitioners face is post-treatment relapse. When we move a lingually placed lateral incisor, central, or palatally impacted cuspid, the key is to get the roots lined up under the crowns so relapse is minimized. The excellent torquing spring (ETS) was born out of my own frustration at watching anterior teeth relapse on occasion.

It will fit on .017 x .025 through .019 x .035 stainless or TMA wire. It doesn’t work as well on nitinol, as the edges of nitinol wire are more rounded.

Once the spring is in position, crimp the last two or three winds on the spring’s coil with a 142 plier and place in the mouth. Then sit back and watch it work.

Alpern

Diagnosing Functional Tongue Space

Michael C. Alpern, DDS, MS

Port Charlotte, Fla

Functional tongue space is critical for each patient. Inadequate functional tongue space can be a cause of anterior tongue thrusting. This can cause anterior or lateral dental open bites that are difficult to close. Adequate functional tongue space is also very important in sleep apnea. Inadequate functional tongue space can contribute to a posterior posturing of the tongue during sleeping, which can cause snoring and airway obstructions.

Inadequate functional tongue space can cause chronic inadvertent biting of the lateral border of the tongue, a primary site of squamous cell carcinoma.

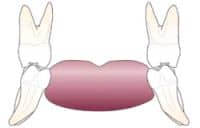

First, look as the patient opens his or her mouth. Do most posterior mandibular teeth appear to lean into the tongue?

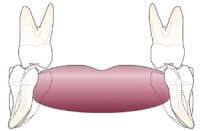

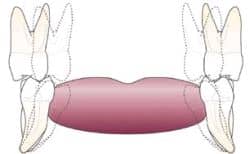

This graphic shows a visualization of moving the most posterior mandibular molars to an uprighted position, giving more functional tongue room.

In my 33 years of clinical orthodontics, I have seen a number of adult patients who have a history of orthodontic treatment with extractions of four bicuspid teeth and later four third molars. A significant number of these patients often complain of difficulty in swallowing because their tongue feels too crowded, so orthodontists should take the amount of functional tongue space into account when considering such extractions.

To diagnose functional tongue space, begin the clinical examination by listening to the patient speak. Is normal speech encumbered? Encourage patients to answer common questions to begin this process. Ask questions about “noisy eating habits.” Ask the patient to swallow. Watch for anterior tongue thrust or abnormal lip and tongue motion.

Once the most posterior mandibular molar has been uprighted, the clinician then visualizes how much palatal expansion is required to bodily move the maxillary most posterior molar to occlude upright on top of the mandibular most posterior molar. The combination of both of these movements can significantly affect deficient functional tongue room, and such visualized expansion may alter a decision on whether or not to extract teeth.

On the initial opening wide of the mouth, observe the most posterior molars. Does the tongue billow out over the lower molars? Are the most posterior mandibular molars lingually proclined into the tongue? If you observe the most posterior molars proclined into the tongue, imagine the molar movement required to upright these molars and move them slightly laterally. Now visualize the amount of bodily maxillary movement required to reposition the maxillary molars vertically over the uprighted mandibular molars.

If the most posterior mandibular molars require uprighting and lateral expansion, and the maxillary molars require bodily lateral movement (usually accomplished with bonded rapid palatal expansion with bite planes), the total effect of these movements may significantly gain arch space. This could solve some crowding problems without extractions.

You can also verify deficient functional tongue room by noting scalloping along the lateral border of the tongue or fissuring of the tongue. Muscles normally do not fold or scallop unless forced to do so by inadequate functional space.

The reader may find these important diagnostic observations helpful in making the all-important extraction or nonextraction decision.