A look at non-surgical and surgical interventions for anterior-posterior problems in the final part of this three-part series exploring how the orthodontist can assist patients with upper airway obstruction and sleep disordered breathing.

By Robert “Tito” Norris, DDS

In Part 1 of this series in this magazine, signs and symptoms of airway issues were discussed (See July/August 2024 issue). Part 2 addressed transverse treatments, with particular attention to Microimplant Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) (See November 2024 issue). This article addresses several solutions for Anterior-Posterior (AP) problems. Selecting which treatment is most applicable for a patient is often based on the severity of the problem, the patient’s tolerance for procedures, and insurance coverage.

Solutions for AP issues essentially fall into two categories: 1) Dento-alveolar solutions and 2) Skeletal solutions. A dento-alveolar solution often includes the addition of bone anteriorly via Surgically Facilitated Orthodontic Treatment (SFOT), and then moving the teeth anteriorly into that new bone. One can expect to achieve 2 to 3 mm of anterior movement of the teeth for each round of SFOT. It is important to notify patients that 2 to 3 rounds of SFOT might be necessary to achieve adequate anterior expansion of the dentition, and often this results in replacing premolars which were previously extracted due to orthodontic treatment.

Case 1: SFOT

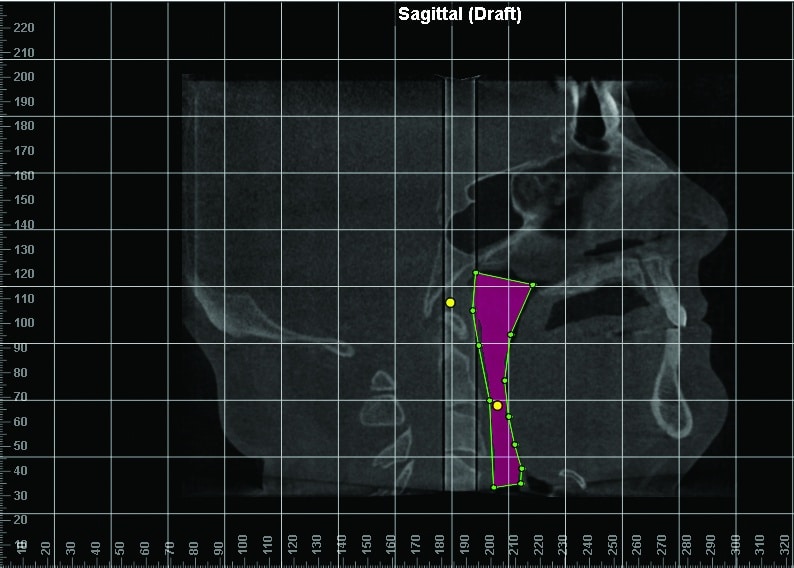

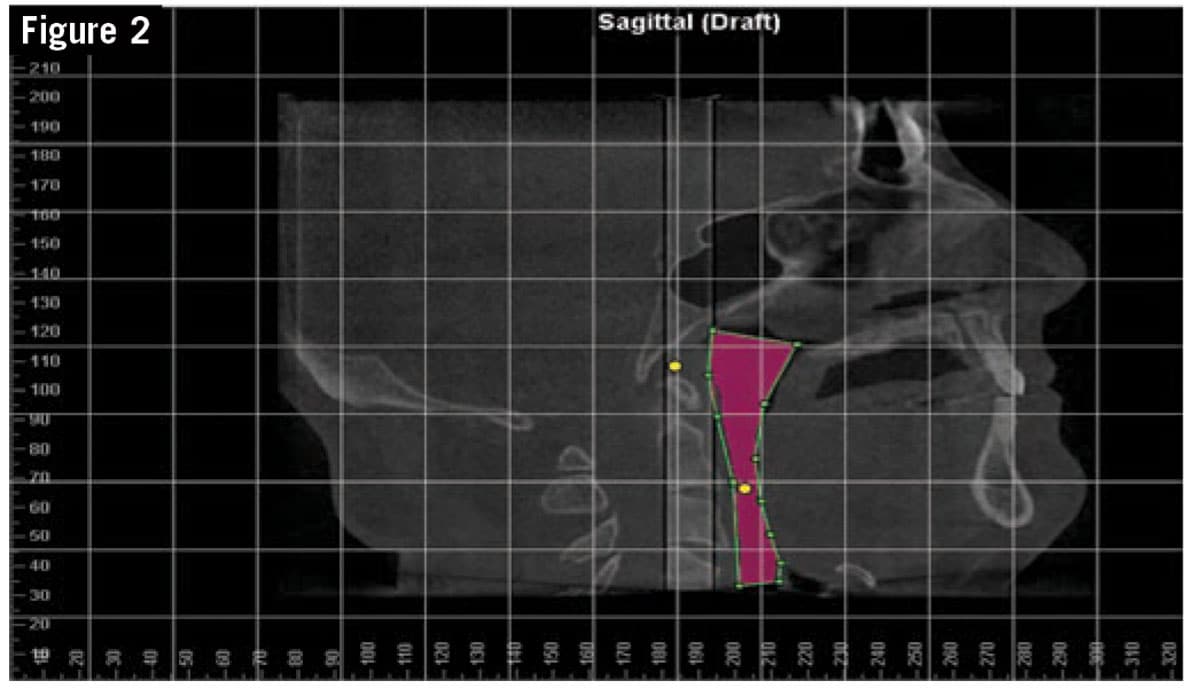

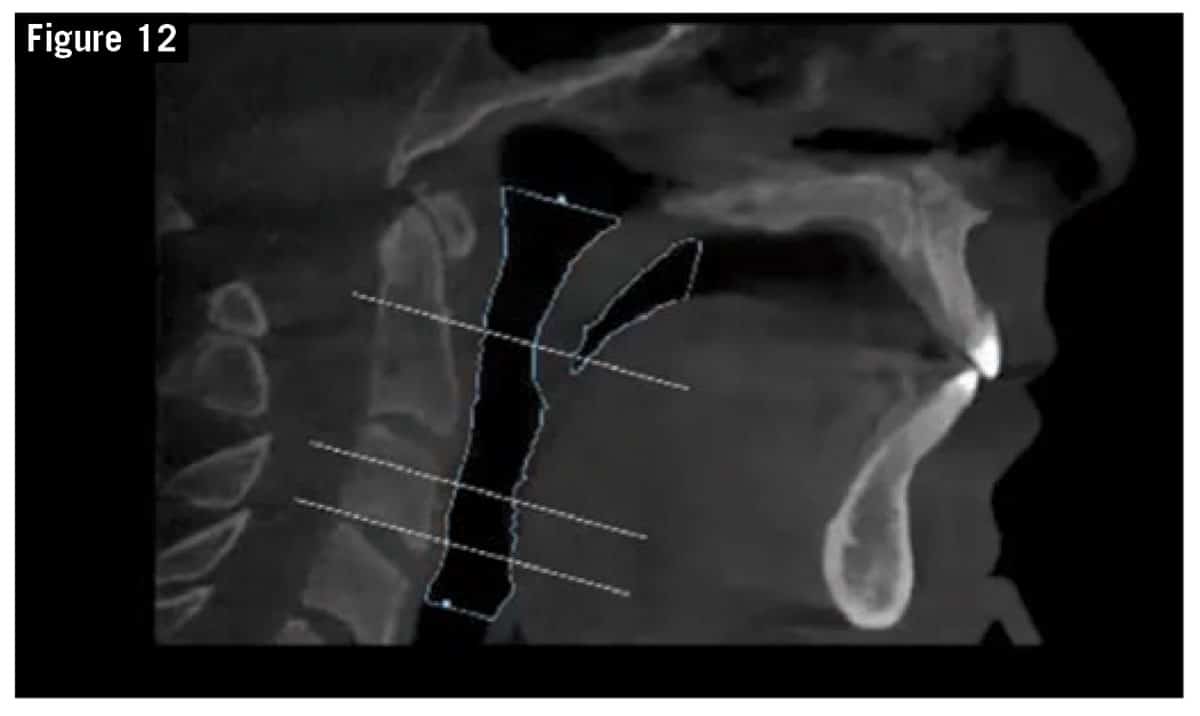

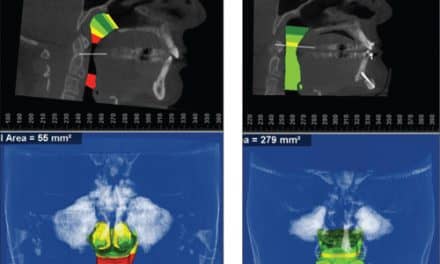

A 56-year-old male (Figure 1) presented with severe generalized wear on his teeth due to nocturnal bruxism. He had retroclined incisors secondary to premolar extractions in his teen years as part of an orthodontic treatment plan. He had a history of snoring and severe sleep apnea with an Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) =40. He experienced daytime sleepiness and had been prescribed a CPAP machine, with which he was moderately compliant. CBCT indicated a Minimal Axial Airway (MAA) of 35 mm2 (Figure 2). Unfortunately, this study was taken with the patient in an elevated head position, which markedly increases the MAA dimension. His actual MAA was likely significantly lower than 35mm2.

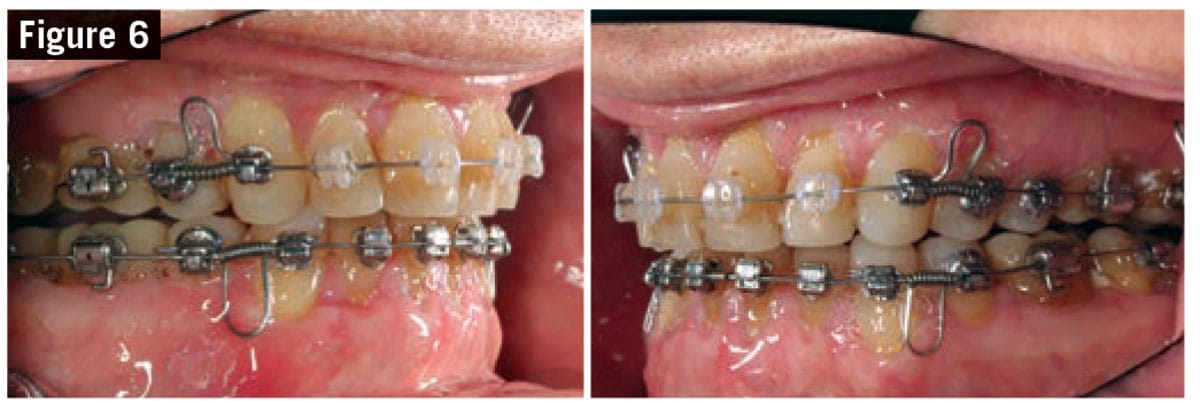

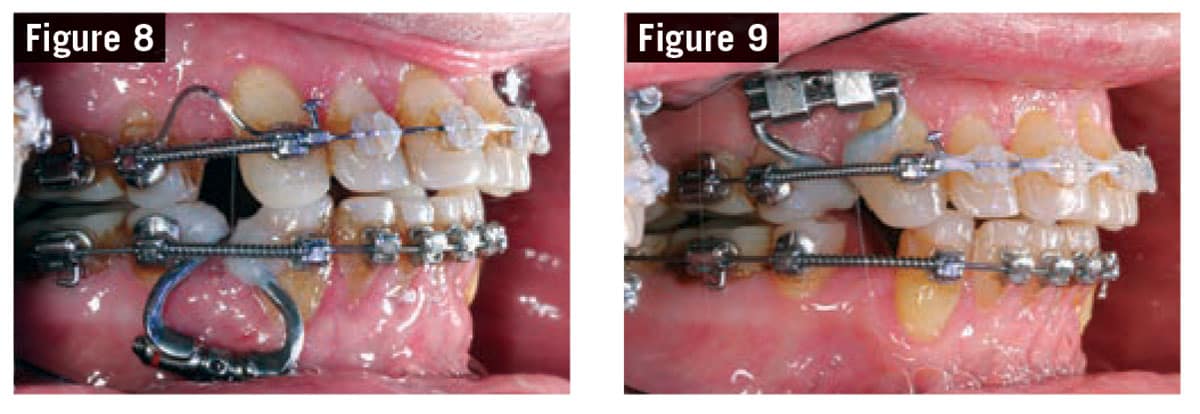

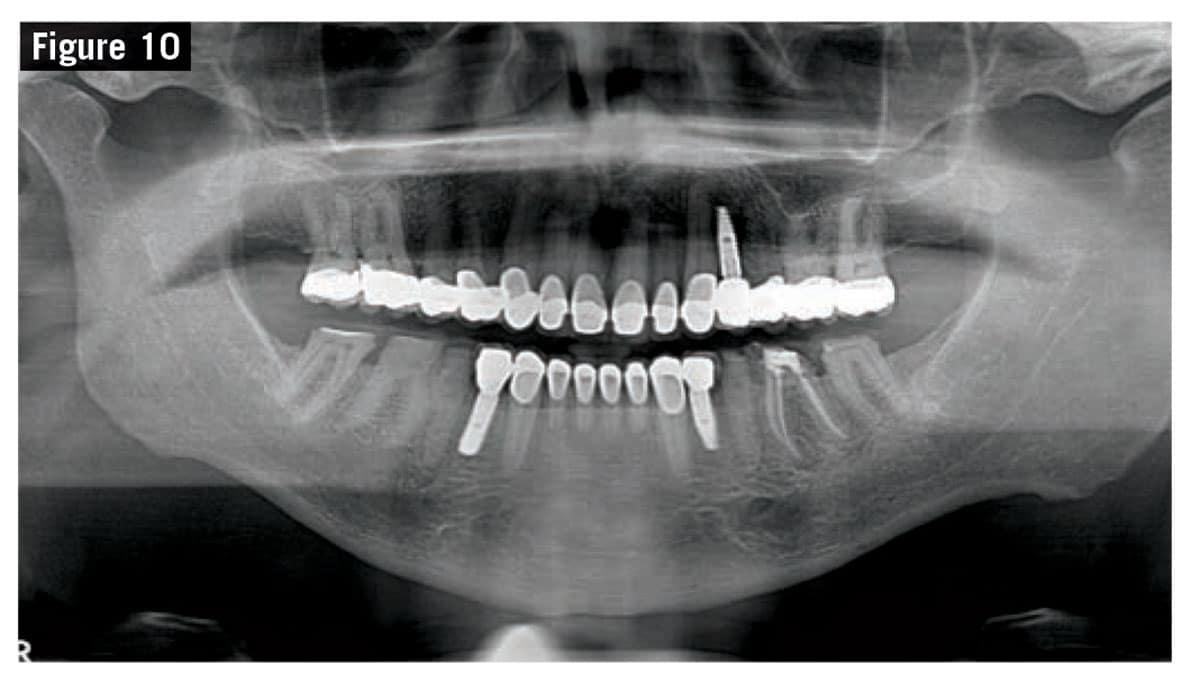

Although a Maxillo-Mandibular advancement was indicated for this patient, he refused to have orthognathic surgery and requested an alternative treatment plan. Following Pre-Orthodontic Provisionalization (Figure 3), orthodontic appliances were placed (Figure 4) and SFOT procedure was performed by a periodontist (Figure 5). Open coil springs and Locatelli Springs were added to initiate space opening mesial to the premolars in all quadrants (Figure 6). Approximately 7 months into treatment, a second round of SFOT was performed in the lower arch (Figure 7). An expander was utilized to complete space opening in the lower left quadrant, and eventually in the upper left quadrant (Figures 8 and 9). Dental implants were placed in three quadrants to replace the missing premolars (Figure 10).

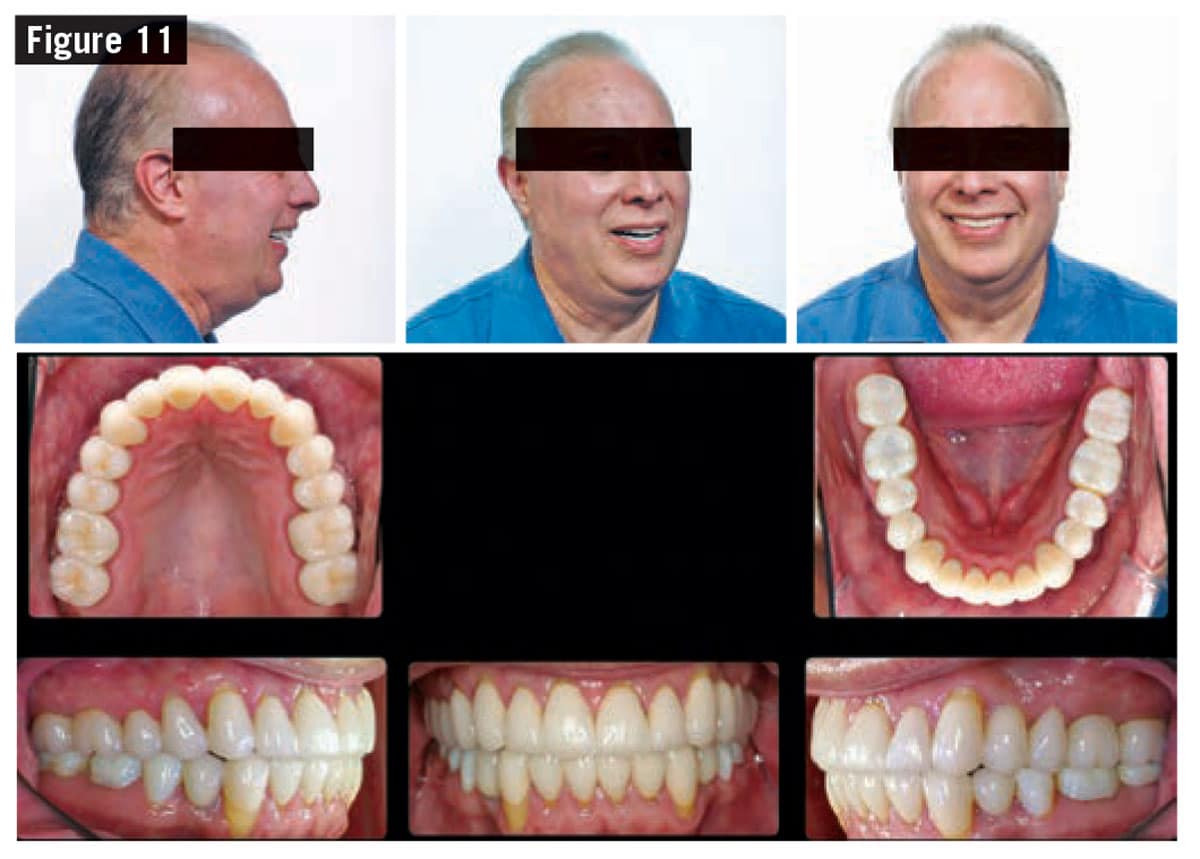

Upon completion of prosthodontic rehabilitation (Figure 11), the patient’s MAA was measured again, showing an increase from 35 mm2 to 251 mm2 (Figure 12). In addition, maxillary incisor position improved dramatically, and now falls perpendicular to soft tissue nasion in the natural head position (Figure 13). The patient’s sleep apnea symptoms also greatly improved.

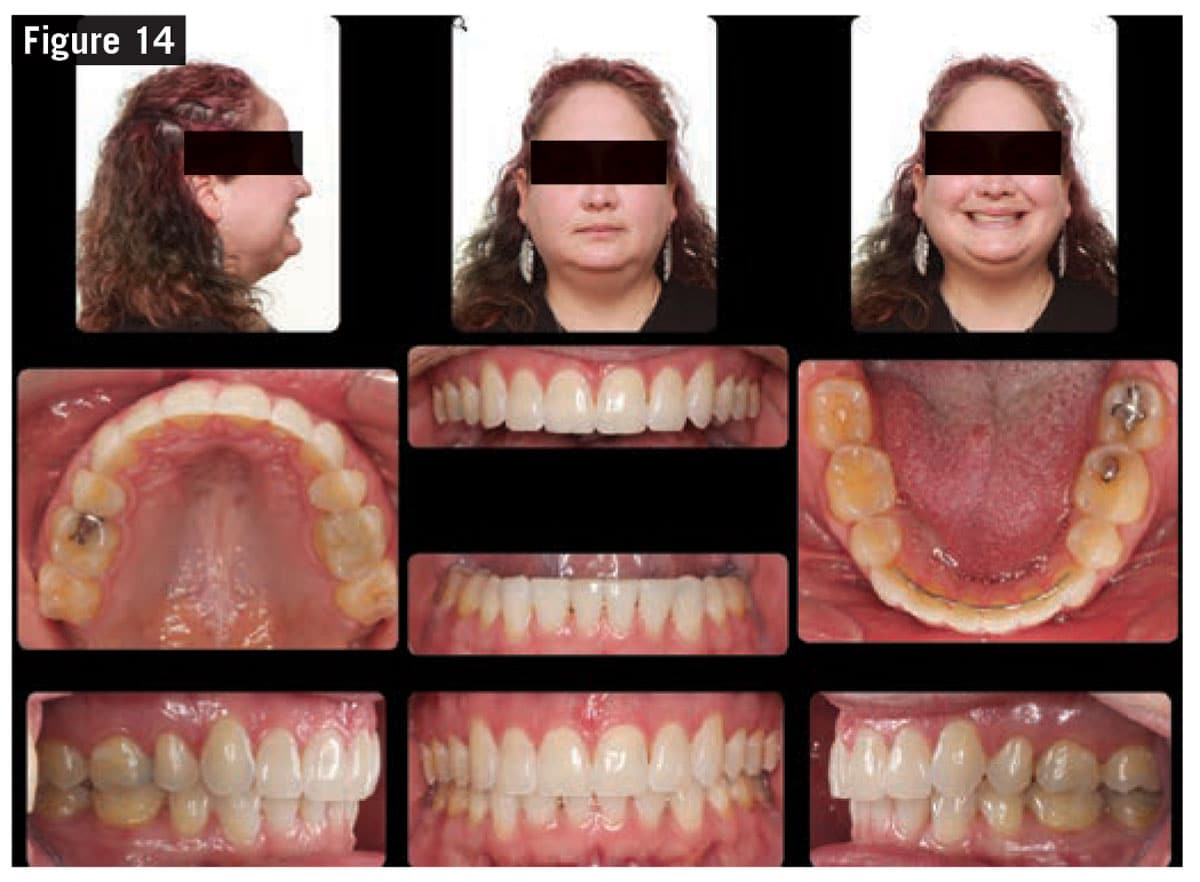

Case 2: Maxillo-Mandibular Advancement

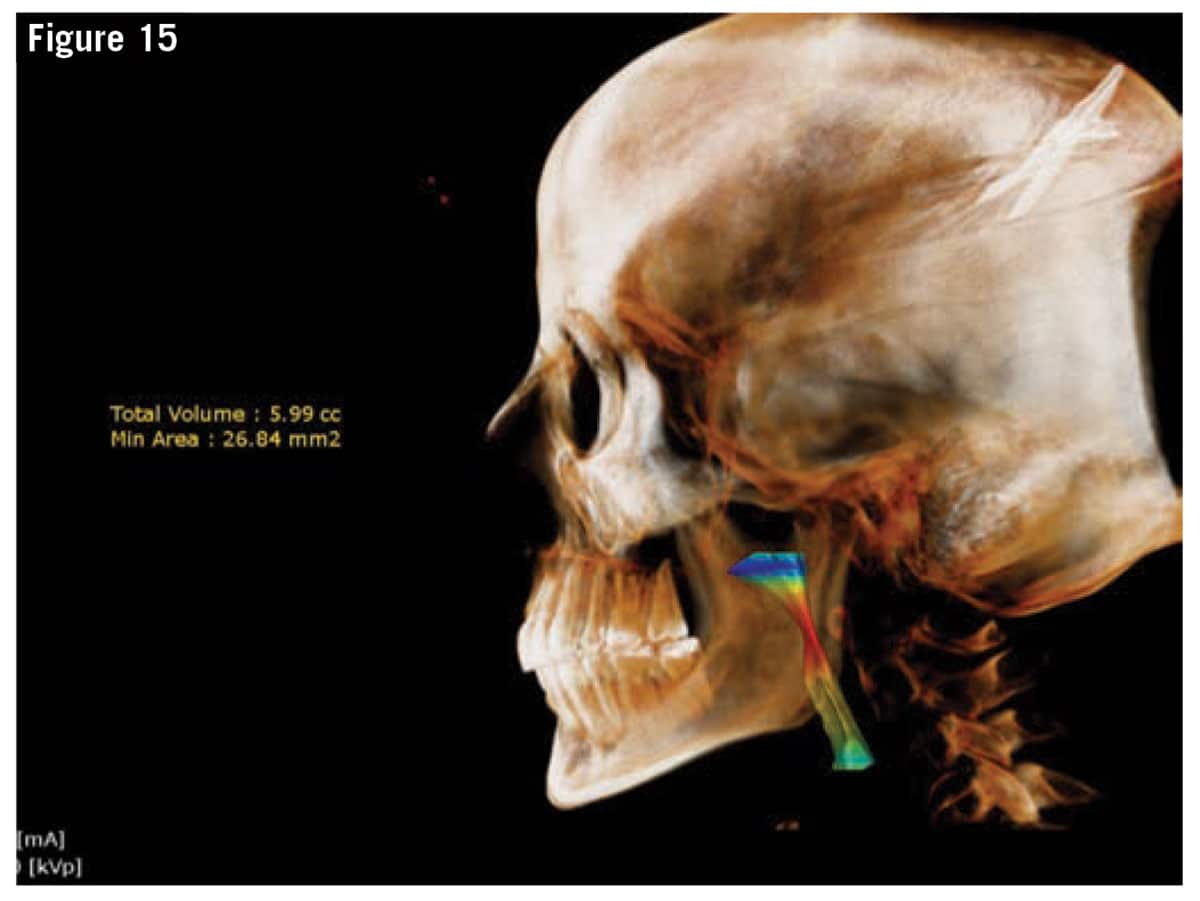

A 38-year-old female presents with severe sleep apnea (AHI=68). She was referred by her ENT physician who is also board certified in Sleep Medicine. The referral was for presurgical orthodontics in preparation for a maxillo-mandibular advancement (MMA). She complained of daytime sleepiness, difficulty waking up in the morning, and daily fatigue. She reported that no matter how long she slept, she never felt rested or refreshed upon waking. Her clinical exam revealed four missing first premolars as a result of orthodontic treatment in her teens (Figure 14). Of particular interest was her MAA of 26 mm2 (Figure 15 and 16), which places her at an extremely high risk of sleep apnea.

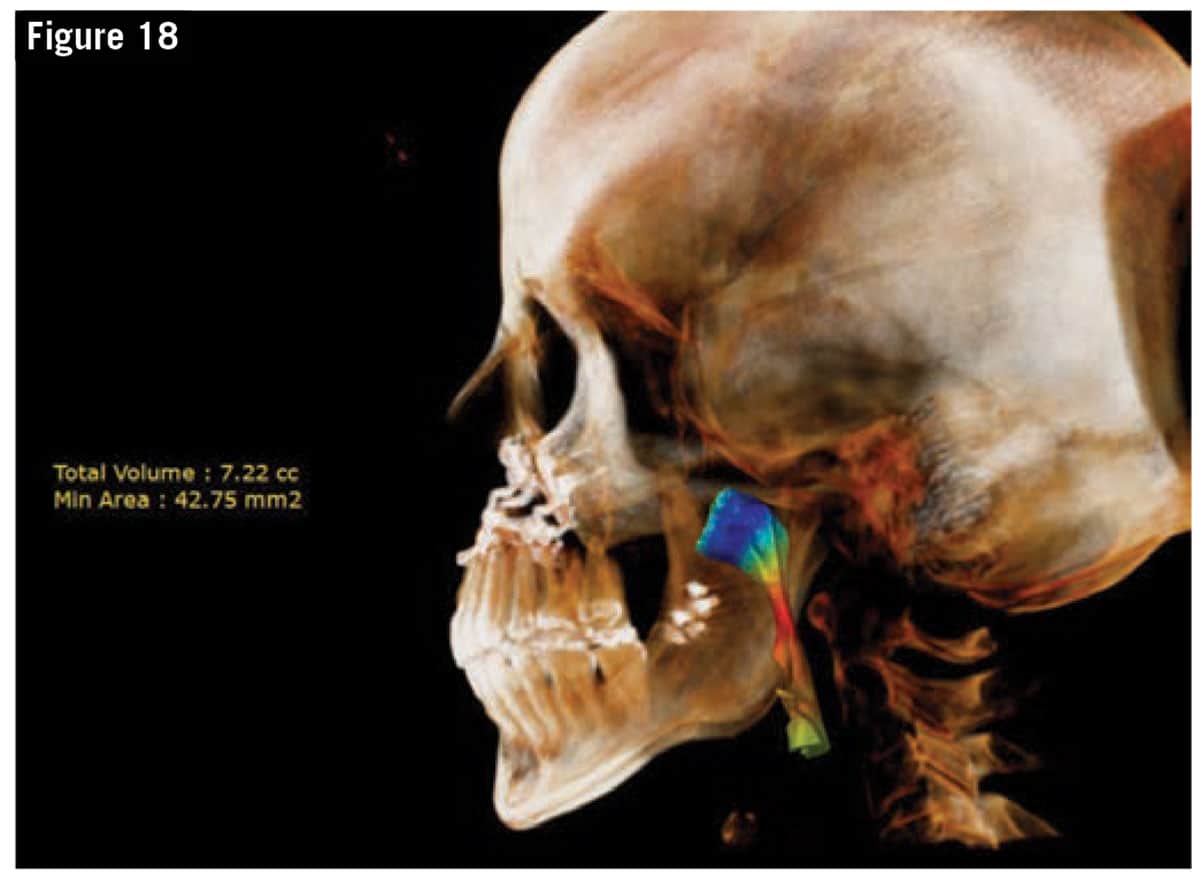

Following MMA surgery (Figure 17), a final CBCT showed doubling of the pharyngeal airway (Figure 18). Even though the post-surgical MAA was still relatively small, it was a significant improvement for her. The bottom line is that her pre-treatment AHI started at 68 and improved to 1.6 post-surgically.

Analysis

In both cases the airway constriction was at the level of the pharyngeal airway. For this reason, anterior movement of the dentition, whether performed surgically or non-surgically, was a beneficial strategy for both patients. Ideally, the first patient could have benefited more by accepting the recommended plan of MMA surgery. Had he undergone this procedure, he could have completely resolved his sleep apnea symptoms and never had to wear his CPAP machine again. Instead he opted for a non-surgical orthodontic compromise, which helped improve his breathing but did not completely resolve his sleep apnea.

The take home message from this series of articles is that orthodontists have a vital role in the recognition and treatment of breathing issues. This starts by having all patients complete an airway/breathing questionnaire, and asking every patient/parent about their airway and breathing status. The addition of a CBCT during the initial examination helps the orthodontist differentiate between nasal breathing issues and constricted pharyngeal breathing issues. It is our duty to educate ourselves in this area so that we can best serve the health and well-being of our patients. As demonstrated in this series of articles, we have a number of tools and techniques to serve our patients in this realm. OP

All case images courtesy of Robert “Tito” Norris, DDS.

Robert “Tito” Norris, DDS, is a board-certified orthodontist in private practice at Stone Oak Orthodontics in San Antonio, Tex. A graduate of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Dental School, he completed a general practice residency at the VA hospital in Washington, DC, and his orthodontic specialty training at Howard University. After serving as a U.S. Air Force orthodontist, he returned to San Antonio to open his practice. Norris, who lectures both nationally and internationally, holds several patents and trademarks, and is the inventor of the Norris 20/26 Passive Self-Ligating Bracket System.