Patients with congenitally missing bicuspids are always a clinical challenge, but with TADs, orthodontists have a significant tool to tackle these cases and find the anchorage they need.

By Eggert Boehlau, DDS, MSc

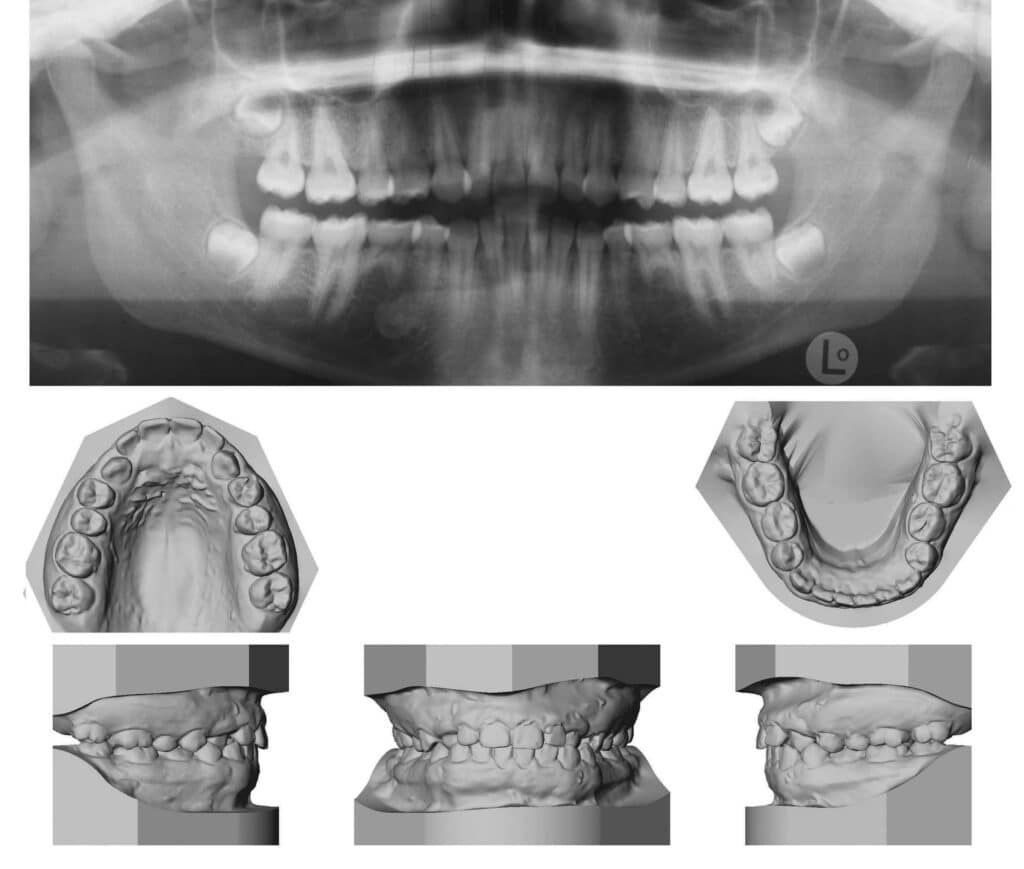

A challenging clinical problem we see on a regular basis involves young patients with congenitally missing unilateral or bilateral second premolars. Population incidence rates vary from 2% to 3%.1-3 Fortunately, these patients often present with developing third molars, which can be utilized in the arches once premolar space closure is achieved.

The introduction of Temporary Anchorage Device (TAD) implants has opened significant additional treatment capabilities for orthodontists, enabling us to tackle cases we were previously unable to do well, primarily due to lack of suitable anchorage.4-6 I remember as an orthodontic resident in the 1990s being advised to be very careful when attempting to close spaces from congenitally missing mandibular premolars since even with good elastics wear, space closure often remained incomplete. I learned over the years that it is rare that a case involving congenitally missing second premolars also presents as a dolichocephalic facial skeletal type with ample dental crowding. To the contrary, in my experience, cases of congenitally missing second premolars are usually brachycephalic facial skeletal types with frequently adequate arch perimeter space, making premolar space closure more challenging.

My personal TAD journey started after the 2005 American Association of Orthodontists meeting in San Francisco, as several presenters were invited to share their early insights into TAD usage. My initial hope was that it would expand the range of orthodontic tooth movements, improve treatment outcomes, and possibly help in cases where limited patient compliance was hindering progress. Over the last 18 years, I have placed over 2,000 TADs. I am not only very comfortable with TAD placement at this point, but I’m also very pleased that I incorporated TADs into my practice. Yes, I have encountered a few complications over the years: one significant palatal infection with cellulitis which resolved quickly after removal of the TAD, loose and lost TADs (around 10%), and two sheared off TADs in the mandibular ascending lingual ramus retromolar area. Fortunately, I have not perforated any dental roots, although some TADs have likely contacted adjacent root surfaces.

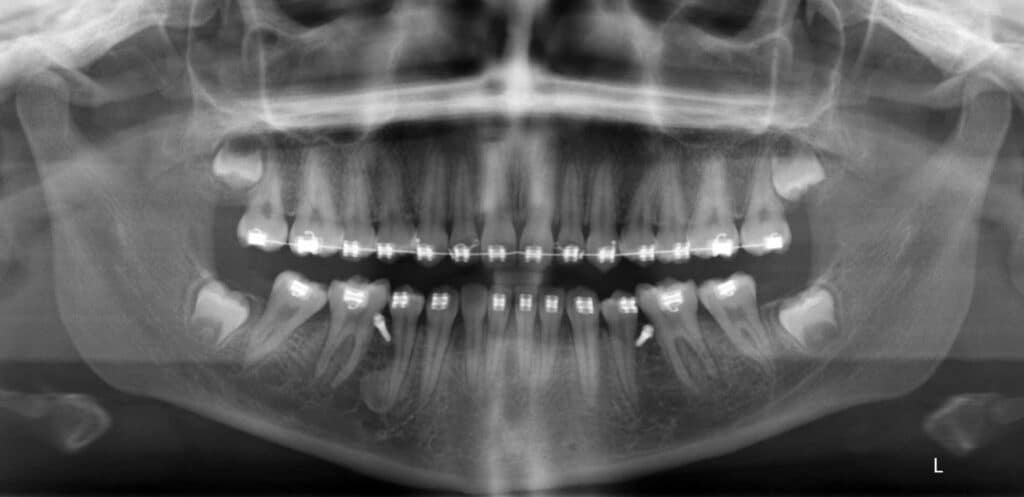

I do not use 3D radiographic imaging to plan TAD placement and have found that a panoramic radiograph is adequate along with careful clinical site evaluation. There are several predictable sites that allow for successful TAD placement in the oral cavity, particularly most of the palate and edentulous sites.

Some orthodontists are hesitant to perform what they perceive to be a surgical procedure in their practices. I would encourage my orthodontic colleagues to overcome the psychological barrier to placing TADs themselves. It is faster and more efficient for me to place a TAD at the same orthodontic appointment than for us to arrange for a referral to another specialist. An added benefit of placing the TAD myself is that I have full control over the position of the implant. The tools required are limited. I prefer using local anesthetic injection. Which means, all that is required in terms of supplies is some topical anesthetic, local anesthetic syringe, and TAD drivers, which are available from TAD vendors. To remove TADs, we usually unscrew them with a Mathieu needle driver, or TAD driver; I rarely use anesthetic on removal.

Other barriers to incorporating TADs in the office is staff perception that TADs cause pain to patients during placement and that the merit of TADs is questionable. The orthodontist must educate the staff regarding these issues at the outset. Staff will become more supportive of TADs once they hear from patients that the TAD placement procedure was easy and post-operative discomfort minimal.

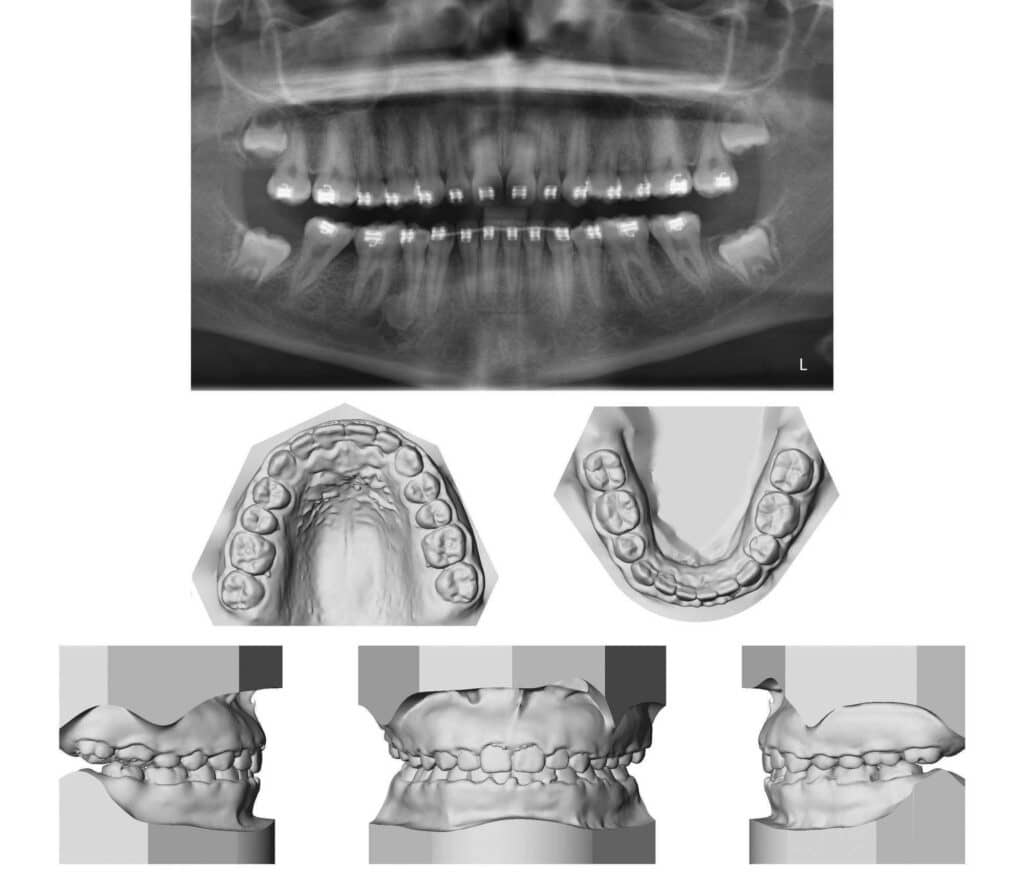

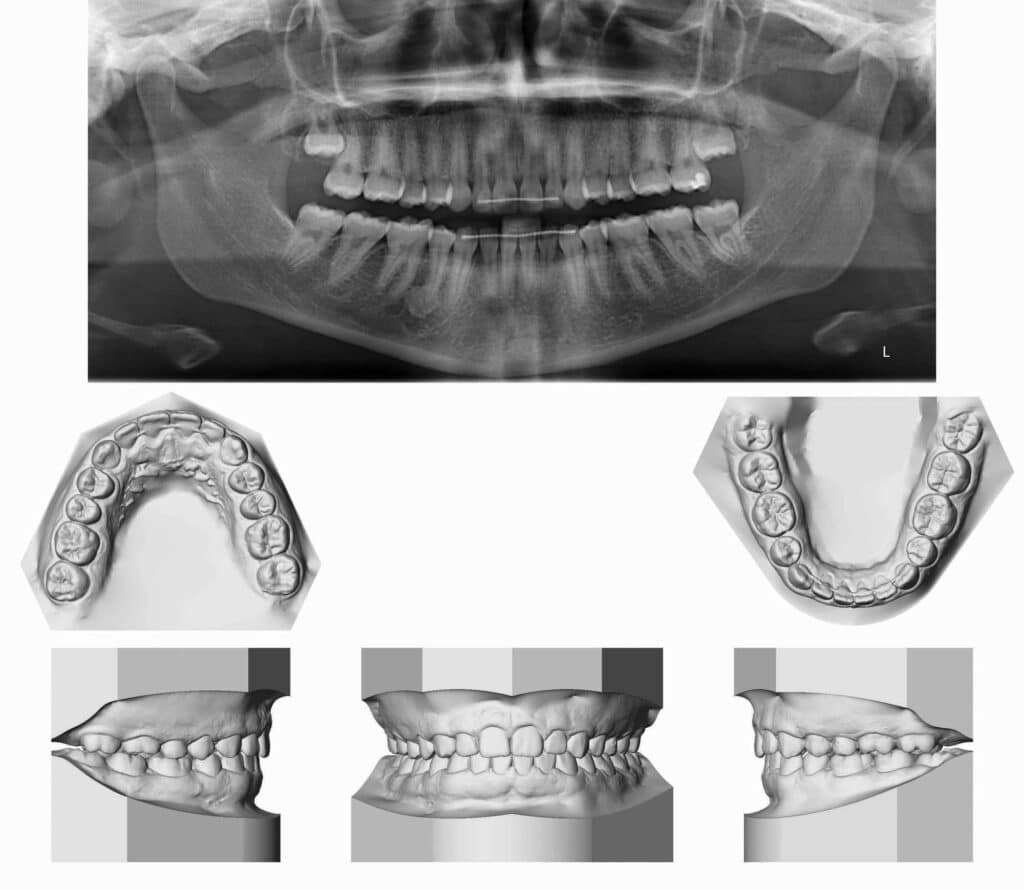

The case here illustrates a sample clinical case and is similar to several we have treated over the last 18 years, where spaces of congenitally missing second premolars were closed. I have found that unilateral and bilateral premolar agenesis cases are equally well treated. Developing mandibular third molars are an important asset, as we require them to provide future occlusal stops for maxillary second molars once the mandibular third molars erupt. Careful maxillary arch retention management is required to prevent over-eruption of maxillary second molars until the mandibular third molars erupt. If you are considering using TADs in your practice, I encourage you to start with these types of cases, since the implant placement site distal to the mandibular first premolars is a very easy and forgiving site to place TAD implants, especially for somebody new to placing TADs themselves.

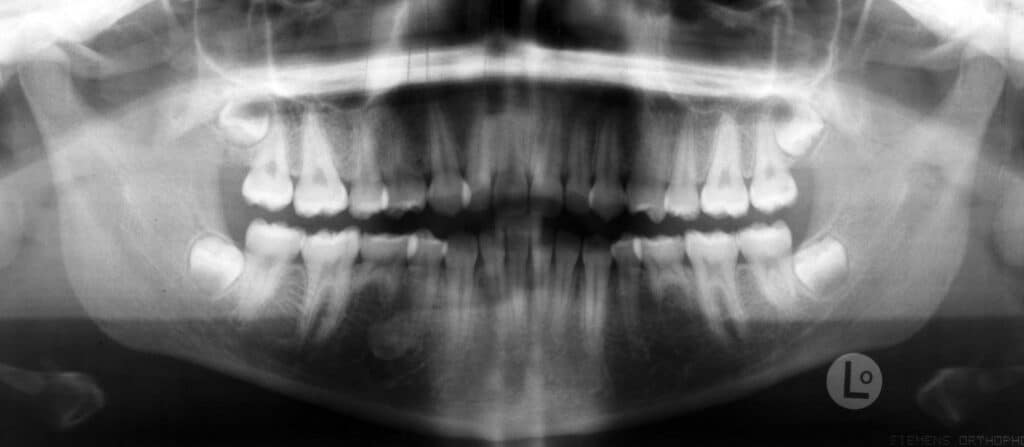

Figure 5: Images show clear change in tooth movements when comparing proximity of teeth to dense bone island in fourth quadrant and associated changes.

It is important to point out the financial advantage of orthodontic treatment with space closure to patients and families. I practice in Ontario, Canada, and the cost of a restored implant in the province of Ontario is about $5,000 CAD ($3,795 USD) and removal of mandibular third molars is about $2,000 CAD ($1,518 USD). Therefore, the total cost of two restored implants and removal of mandibular third molars is about $12,000 CAD ($9,108 USD). Moreover, implants have a finite lifespan. Thus, if placed in a young adult, it is reasonable to assume that the implants may eventually fail, resulting in the additional cost of replacing the implants and restorations. In comparison, the cost of an orthodontic treatment plan with space closure is significantly less than the above extraction/prosthetic solution, avoiding the risk of one or both implants/restorations failing. I frequently joke that when considering the above alternative costs that the orthodontic solution is free. You also must counsel your local dentists and oral surgeons, as they sometimes are inclined to extract any third molar they encounter without realizing that it needs to be retained. I have seen this on several occasions—patients come to see me years after having a perfectly erupted functional third molar removed—and I am always disappointed.

In my opinion, the use of TADs and space closure represents the standard of care. I have already seen several cases from colleagues in Europe, as well as those in my own practice, that show TADs can be successfully handled in this fashion. OP

Eggert Boehlau, DDS, MSc, is an orthodontist in private practice in Toronto and Barrie, Ontario, Canada. Boehlau is a graduate of University of Toronto Faculty of Dentistry as well as the orthodontic graduate program. He completed his Master of Science in oral biology at the University of Alberta. Boehlau is a diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics.

References:

- Bergström K . An orthopantomographic study of hypodontia, supernumeraries and other anomalies in school children between the ages of 8–9 years. An epidemiological study. Swed Dent J 1977; 1 (4): 145–157.

- Locht S . Panoramic radiographic examination of 704 Danish children aged 9-10 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1980; 8 (7): 375–380.

- Polder BJ, Van’t Hof MA, Van der Linden FP et al. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32 (3): 217–226.

- Creekmore TD, Eklund MK. The possibility of skeletal anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 17:266-269, 1983.

- Kanomi R. Mini-implant for orthodontic anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 31:763-767, 1997.

- Gray JB, Smith R. Transitional implants for orthodontic anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 34:659-666, 2000.