by Michael C. Alpern, DDS, MS; and Douglas G. Nuelle, MD, FACS

Clinical tools to help orthodontists diagnose TMD

|

Each patient has two temporomandibular joints, or TMJs. For clarity’s sake, we must delineate between the public’s common name and current orthodontic-orthopaedic surgical concepts of TMJ dysfunction or TMD.

Diagnosis

Patients often approach orthodontists and dentists complaining that they have “TMJ.” In reality, they are suffering from TMJ symptoms such as clicking, popping, clunking, locking, jaw-joint shifting, or pain in one or both TMJs. They may also suffer from pain in the four groups of muscles involved in TMJ movement: temporalis, masseter, medial, and lateral pterygoids. Since many muscles of the head are innervated by nerves close to the brain, patients may also complain of neck pain and radiating pain to other areas of the head.

We divide these symptoms into joint dysfunction and muscle and capsular pain.

TMD or joint dysfunction usually involves the inability of the mandibular condyles and associated diskal tissue and associated viscoelastic tissues to move unencumbered. This implies a lack of freedom of movement due to obstructions within the capsule surrounding the condyles and associated disks. Normal, healthy TMJ’s condyles and disks must have unencumbered freedom of motion. The condyles and disks must be able to move together in an unencumbered fashion. Any encumbrances to freedom of motion can produce abnormal movements of the condyles and disks. These abnormal movements stretch the pericapsular tissues, activating nerves and producing pain in the attached muscles.

|

| Michael C. Alpern, DDS, MS |

|

| Douglas G. Nuelle, MD, FACS |

It is important to realize that the fragile fibrocartilage lining the TMJ fossa and eminence and the disk do not have any nerve supply or blood supply. Therefore, any injury to these fibrocartilaginous tissues does not notify the brain of such injury. And with no blood supply, this cartilage cannot undergo normal healing.

Pain occurs only when either of the condyles or disks moves abnormally due to encumbrances to freedom of motion. This causes abnormal stretching or movement of the pericapsular tissues, which do have a nerve supply. These nerves send messages to the brain, eliciting muscle splinting or cramping and pain.

TMJ fibrocartilaginous tissue (including the TMJ disk) either functions normally or wears (or degenerates). TMJ fibrocartilaginous tissue is designed to be loaded approximately 7 to 17 minutes per day. This usually occurs with normal chewing, talking, and swallowing. During this normal function, the degree of fibrocartilaginous loading is intermittent, and light forces are applied. Because it lacks proteoglycans (present in hyaline cartilage), fibrocartilage cannot tolerate any excessive loading (either constant or heavy loading), which results in cartilage wearing or degeneration.

When TMJ fibrocartilage abnormally wears or degenerates, the surface of this cartilage develops indentations, divots, or obstructions we call speed bumps. Divots or speed bumps of dead cartilage cause obstructions to the freedom of motion of the condyles and disks. Again, this abnormal motion stretches the pericapsular tissues, eliciting pain fibers, which cause a reactive muscle splinting or spasm—and pain.

Causes of Abnormal TMJ Loading

Abnormal TMJ loading occurs for two reasons: excessive force and prolonged excessive time.

Excessive force can be caused by trauma such as blows or blunt-force trauma to the face, teeth, and jaws (for example, from falling or in swimming pool accidents). There are a significant number of abused patients who receive trauma from a spouse or family member.

However, most excessive force and excessive time loading is the result of patients’ inadvertently or unintentionally self-destructive habits. People all over the world have become jaw leaners. Notice any family with children, and most often the children can be seen lying on the floor leaning on their jaws for hours and hours as they watch television. Other children, adolescents, and adults spend hours at their computers with one hand on the mouse and the other supporting their face or jaws. School students often sit at their desks chronically leaning on their jaws.

To make matters worse, these same individuals sleep either on one side—or worse, sleep on their stomachs. Consider a 65-pound teenager who chronically leans on her jaw at school and at home for 4 to 8 hours per day. Then she sleeps on her stomach or on one side of her face. Consider the weight of the head and the weight of the neck and shoulders. Even a conservative estimate would be 10 to 30 pounds of constant, heavy loading for more than 4 to 8 hours per day. (As an orthodontist, I try never to apply Class III elastics of more than 4 ounces.)

|

|

|

Clockwise from upper right: The clinician asks the patient to open and close and observes any deviations in opening and closing; using a Boley gauge to measure maximum opening (note that the gauge is extended until it contacts the upper and lower incisors); using the Boley gauge to accurately measure the patient’s maximum movement to the right and left. |

This does not even consider the stress of today’s life, which many sensitive, caring, pleasing, perfectionists endure during the day. These same individuals tend to internalize this stress and express it with severe tooth grinding and/or clenching during rapid eye movement sleep.

The total result of all this excessive loading wears and degenerates the TMJ fibrocartilage lining the TMJ fossa or socket, and causes similar permanent damage to the fibrocartilaginous disk.

Symptoms to Look For

We have found that a detailed TMJ history (added to a normal orthodontic history) is critical to identify a history of trauma, including the chronic destructive habits mentioned above, but also including gum chewing, ice chewing, and chewing objects such as pens, pencils, fingernails, lips—the list can be endless.

We have added a generalized series of questions to our standard orthodontic patient questionnaire. If a patient answers many of these questions in a way that suggests abnormal TMJ loading, then we give the patient a separate, TMJ-specific questionnaire. This requires an average of 45 minutes of patient time to carefully document all of the above in addition to their symptoms or complaints. The most important history and symptoms to document is locking or difficulty in opening and closing the mandible.

The TMJ Clinical Examination

In addition to specific malocclusion documentation, we also do the following:

- Using a ruler, evaluate deviations in opening and closing;

- Using a boley gauge, carefully measure mandibular range of motion, including maximum opening as well as right and left lateral range of movement. Both of the above should be noted in ink on the examination chart.

- Place the forefingers lightly over each right and left TMJ, and feel for the indentation that occurs on opening and closing. Normally, the patient should be able to move both condyles and associated disks down and out of their associated fossae. As the condyles and disks move down and out of their fossae, the clinician should lightly feel his fingers move into the fossa as the condyles and disks move out. If the clinician does not feel his fingers moving into the space vacated by the condyles and disks (in a repeated fashion), this would tend to be strong evidence that unencumbered freedom of motion is not possible and TMD is present. Radiographs and “cine” (motion) MRI images can verify this important clinical finding.

- Bimanual palpation of the right and left temporalis, masseter, and medial pterygoid muscles should verify or find any muscle tenderness or pain.

It is critically important to realize that TMD pain is often observed in the temporalis, masseter, and medial pterygoid muscles. Neck pain, frontal headaches, sagittal headaches, eye pain, and sinus pain can also be present, but this pain requires a team approach. The team could include an orthodontist, a board-certified neurologist, and an ENT. Records should include full-mouth radiographs and full-mouth periodontal charting.

|

|

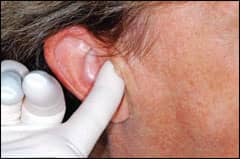

| The clinician uses the forefinger on each side to lightly palpate the lateral pole of the right and left TMJ condyles. The goal is to see if the fingers will move inward as the condyles and disks move out of the fossa and feel for clicking, popping, or encumbrances to freedom of motion. | The clinician inserts the little fingers of each hand into the ear and presses gently up and forward. As the patient opens and closes, the clinician feels for a bump of the condyles as the patient commences final closure. |

|

|

| Palpation of the right temporalis muscle. | Palpation of the medial pterygoid muscles. |

One key questions we have learned to ask is: does the patient ever wake up with a headache? If this is occurring, we believe it is critical to have the patient completely evaluated by a board-certified neurologist. The orthodontist must receive a complete diagnostic workup, including copies of all tests from the neurologist.

If the result of any of the previous findings are positive or suspicious for TMD, then TMJ imaging is very important. Panoramic radiographs are general scanning images. Most tests have shown that the patient’s TMJs are not accurately within the main focal trough of most current or previous panoramic machines. Therefore, corrected sagittal 1 mm or less tomographic cuts taken every 3 millimeters from the lateral pole to the medial pole of each condlye are very important. These images can also be obtained using 3D cone beam CT machines using the same or better standards of imaging.

It is important to see all the tomographic or CT cuts or images (not just the pretty center cuts) because we have found most abnormalities are often near the medial poles.

If a significant intercapsular motion problem is found on clinical examination, then a cine MRI study should be completed. These studies should clearly show that the disk moves with the condyle. Failure of the disk to move with the condyle is often associated with adhesive capsulitis, in which the disk is “stuck” to the fossa and thus the condyle tears out from under the disk, causing abnormal motion and pain.

Finally, we have found that in a significant number of patients, condyles and the disk will move forward together in opening and nearly complete the closing movements. However, in the final closing movements as the teeth begin to contact, the condyle will slip off the posterior ridge of the disk and move toward the patient’s ear complex. This can be clinically replicated by very carefully placing the clinician’s little fingers up and slightly forward in the patient’s ear canal.

|

To read more articles about this topic, search for “TMD.” |

Ask the patient to open and close. If you feel the condyles bump against the tips of your little fingers as the patient closes his teeth together in maximum interdigitation, and if the patient has ear symptoms such as stuffiness, ringing, and ear pain not found by an ENT to be infectious or inflammatory, then the condyle slipping off the disk on one or both sides should be suspected.

Michael C. Alpern, DDS, MS, is in private practice in Port Charlotte, Fla. He can be reached at

Douglas G. Nuelle, MD, FACS, is in private practice in orthopedic surgery in Blue Mountain, Ga. He is the author of numerous lectures and articles on TMJ arthroscopy. He can be reached at

This is the first of a two-part series on TMD.