Accommodating emergency orthodontic appointments is a daily challenge for a busy orthodontic practice. The most common orthodontic emergencies include: broken brackets, loose bands, poking wires, tooth discomfort, soft tissue irritation, lost or broken retainers, loose appliances, difficulty turning the expander screw, and less commonly traumatic dental injuries. However, they also include anything where the patient simply wants to be seen, such as an appointment to address concerns.

-

Neal D. Kravitz, DMD, MS, is in the private practice of orthodontics in South Riding and Ashburn, Va, and White Plains, Md. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics, a member of the Edward Angle Honor Society, and an adjunct faculty at Washington Hospital Center. Kravitz has been published in numerous orthodontic journals, books, and educational materials. He lectures throughout the country and internationally on modern advancements in orthodontics, lingual orthodontics, treatment planning, and practice management. He can be reached at [email protected].

The following article will review management of orthodontic emergencies in my office. I will share my philosophy of emergency care, provide a schedule template, and discuss the handling of the actual appointment from the initial phone call to the completion of the procedure.

Statistics

Our office typically sees anywhere from five to eight emergency appointments per day based on an average workday of 160 patients, which equates to 3% to 5% of our daily appointments. Though many orthodontic emergencies are handled over the phone with a trained staff member, encouraging the use of silicone wax or a fingernail clipper, I actually welcome patients who would like to be seen to come in immediately. We use this appointment to built rapport and strengthen our reputation for always accommodating our patients’ needs.

Scheduling Template

Our office is open from 7:30 am to 7 pm, with a 2-hour lunch from noon to 2 pm. Ideally, I prefer to see emergencies between 2 pm and 2:20 pm, immediately following our lunch break. My rationale is that parents will be more agreeable to schedule an appointment at this time, as their children will have attended the majority of school. Likewise, working parents can easily adjust their own lunch break to come into the office. Typically, it is not a problem to overbook this time slot, as many scheduled patients arrive a few minutes early or late immediately following lunch. If there are multiple emergency appointments, we ask patients to come in a little early, and our lunch break can easily be shortened to accommodate the workload.

If there are no vacancies on the schedule or the patient simply refuses this time slot, then I prefer to see emergencies before work at 7:30 am, or, as a last resort, at the end of the day when the schedule lightens. Simply put, I absolutely do not want emergency appointments to affect the flow of my day, and particularly make me late for afternoon new patient consultations. I would rather come in early, shorten my lunch break, or even stay a few minutes late after work if it keeps the office running smoothly. My time is not more important than my patients. My staff understands the equation: If we can reduce our emergencies, our workday is lighter.

The exception to the rule is emergency patients who experience broken brackets the day of their bonding appointment. These patients will not accept coming in any time other than when it is most convenient for them. After all, we have just inconvenienced them again. When they arrive, they may be frustrated, defiant that their child did nothing wrong, and even question the strength of my bonding agent or technique. In these situations, I am humble, apologetic, and my staff is trained to seat the patient in a clinical chair the moment they walk back through the office door.

I discourage the use of rigid templates with emergency blocks sprinkled throughout the day. Our office schedule is too busy to accommodate vacancies. The challenge with patient scheduling is that any rules with regard to scheduling blocks are written in sand. At the last moment, appointments may be added, canceled, or lengthened; employees may need meetings for instruction or disciplining; parents may need private consultations to review treatment progress; phone calls may need answering; and administrative decisions may require immediate attention. Therefore, to ensure adequate time exists to see emergency appointments, I always try to create more clinical time. “Fill vacancies to create vacancies,” as I like to say.

Handling the Emergency Appointment

When an emergency patient calls the office or my cell phone to schedule an appointment, I always try to use language that is solution-oriented. I never like to simply respond, “No, that time is not available.” Rather, I prefer to reword my response in a positive manner: “Mrs. Smith, I understand you would prefer 4 pm. Your time is very valuable to us. Right now I can fit you in today at 2 pm if that time is acceptable to you. I have your cellphone and a Post-It on my computer to call you first thing if a vacancy opens later in the afternoon.”[sidebar float=”right” width=”300″]?Dr Kravitz’s Top 10 Principles of Emergency Management

1) Never be too busy to pick up the phone.

2) Respond immediately.

3) Do not dismiss a patient’s concerns. My patient’s feelings are always valid.

4) My time is not more important than my patients.

5) Do not charge the patient for broken brackets, no matter the number of breakages.

6) Schedule most emergencies before work, immediately after lunch, or even after work to avoid congesting your workday and affecting

the flow of afternoon consultations.

7) If a bracket breaks the day of initial bonding, always see the patient that same day.

8) Keep a hotlist ready to call emergency patients in case of a last-minute cancellation.

9) Do not lecture the parent or scold the child. Assume full responsibility.

10) At the emergency appointment, attempt to proceed to the following appointment. If a bracket breaks, reposition any needed brackets if time permits.[/sidebar]

If I have a particular choice of words that I would like a new-hire to use, I will simply type the phrase on a strip of paper and tape it to his/her computer. The perception to the patient must always be that: (1) we are sorry this happened and (2) we are making every possible effort to correct the problem as soon as possible.

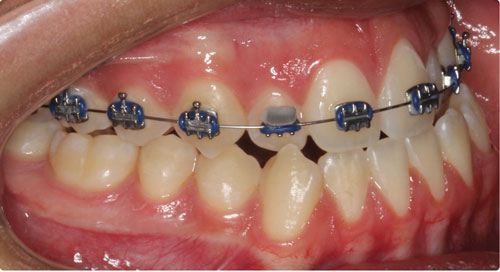

The two most common emergencies in my office are broken brackets and loose or poking wires. For patients with broken brackets, my staff is trained to have the station ready before the patient is seated, including: bracket tray, L-Pop, luting agent, handpiece with bur inserted, retractors, and suction tips. I would like the wire already removed and the patient’s teeth brushed, if necessary, when I arrive. I never rebond the same bracket or bond over old cement. Rebonding one or two brackets should take minutes.

If time permits, I will reposition as many teeth as possible without taking a panorex. I double-check occlusal clearance, and then I put pressure on the new bracket with my thumb to ensure it is firmly cemented. I will also attempt to proceed to the next appointment and wire size. Advancing to the next appointment is a wonderful way of taking a negative experience for the patient and making it positive.

If the oral hygiene is poor, I will place a closed-coil spring to maintain the space and explain to the parent the need to “let the gums heal” before rebonding the bracket. If a molar tube is off for the second time, I will attempt to band the tooth at the emergency appointment rather than place spacers and reschedule, though this is not always possible. I always train my staff to rarely clip the wire as an alternative to rebonding the bracket, as many parents will interpret this as “lazy” and question why they made the trip to your office.

For loose or poking wires, we will often seat the patient in the records room, as a full-station setup is rarely required. Oftentimes, this procedure is entirely delegated to the orthodontic technician. In my office, my staff is trained to only run continuous wires if: (1) there is a bracket bonded on the tooth before the last or (2) the wire is 0.018 NiTi or thicker.

For example, I never run a continuous 0.014 NiTi wire on a Phase I patient with a 2 x 4, as it will always pull out from the molar tube, no matter the strength of the cinch. Thinner wires, such as 0.012 and 0.014 NiTi, are only placed continuously through the first molar tubes if the second premolar brackets are bonded. I often will check the quality of the technician’s cinch after the appointment by tugging on the wire.

Conclusion

Orthodontic emergencies are often infrequent and not severe; however, addressing patient concerns should not be taken lightly. I respond immediately and make all effort to see the patient that same day, ideally before work or after lunch. The negative experience of an orthodontic emergency is an opportunity to create a positive moment that generates rapport.

In today’s consumer-driven society empowered by social media and doctor review sites where customer service reigns supreme, orthodontists can no longer ask the patient to wait until their next appointment to be seen. OP