Young orthodontists entering the profession once dreamed of being the owner, not the employee. But times have changed. With student debt weighing heavily, this group is increasingly looking for associate and partnership opportunities. But that isn’t the only motivating factor in their decision. As Bentson Copple & Associates’ 2016 Residents Survey discovered, young orthodontists are drawn to practice models that offer mentorship opportunities and a collaborative work-culture, rather than a competitive one. They welcome a team, group-based environment.

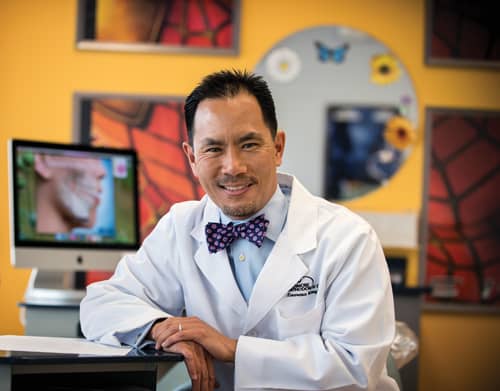

If that’s the case, then a large group practice might be what a young orthodontist entering private practice is looking for—so says, Baltimore, Md-based orthodontist Lawrence Wang, DDS, MS.

The doctors of Baltimore Orthodontic Group. Top row: Michael Riger, DMD, MS; Kenneth Kyser, DDS; Wang. Bottom row: Dalia Shlash, DDS, MPH; Anna Muench, DDS, MS; Erin Mahoney, DDS.

How large?

Six orthodontists. Five locations.

When Wang completed his residency at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey 19 years ago, he experienced something few young orthodontists do today. Within 2 weeks of completing his residency, he had three full-time positions on offer—one of which was an associate position with an existing four-partner practice with two locations. Over the ensuing years, that practice has grown into a six-doctor, five-location operation: the Baltimore Orthodontic Group.

While stories of partnerships gone wrong and bad breakups leave many wary of such a large practice, Wang champions the model.

In this model, Wang stresses the importance of embracing the new associate as a full member of the group from the get-go. Wang recalls how on his first day, his nameplate was ready and his name added to the group’s stationery. Within a week, his name was on the door of each location. “I know those things aren’t a big deal to some people, but as a new resident coming out, they went the extra mile to welcome me. We still do that now. Right away, you come in feeling like I’m part of the practice.”

And that sense of being a full member of the practice extends to business decisions. When management decisions came up while Wang was still an associate, the partners asked for his opinion. No, he didn’t have a vote, but being asked his opinion and having it considered went a long way in making him feel like a member of a team.

[sidebar float=”right” width=”250″]

PRACTICE PROFILE

Practice name: Baltimore Orthodontic Group

Locations: Five locations in Maryland—Catonsville, Eastpoint, Eldersburg, Ellicott City, and Lutherville

Number of chairs: 7 chairs in each office

Staff members: 55

Years in practice: 19

Education: Bachelor of Science, University of Toronto; Doctor of Dental Surgery, Northwestern University Dental School; Post-Graduate Orthodontic Program, Rutgers University (formerly UMDNJ); Masters in Oral Biology, Rutgers University (formerly UMNDJ)

Average number of patients per day: 60

Days worked per month: 15

Top products used: topsOrtho™ (tops Software); Ortho Sesame (Sesame Communications); iTero® Element™ (Align Technology Inc); Invisalign® (Align Technology Inc); GAC In-Ovation® R and C (Dentsply Sirona Orthodontics); Unitek Transbond™ XT Light Cure Adhesive (3M Oral Care); Assure PLUS All Surface Bonding Resin (Reliance Orthodontic Products); Forsus™ Class II Correction System (3M Oral Care); Carrière Motion Class II Appliance (Henry Schein Orthodontics)

Website: baltimoreorthodonticgroup.com

[/sidebar]

And yes, while being part of a group might run counter to the idea of autonomy, nothing could be further from the truth in Wang’s experience. In fact, he argues that giving associates autonomy is key to their success in such a large group.

He explains it this way, “What I mean by autonomy is you’ve learned a certain way. Yes, you’re still new, but we’re willing to let you treat patients as you see fit. Some offices you go into, the doctor says this is how I do it; this is how we’ve been doing it; and this is how you are going to do it.”

That’s not to say that the senior doctors don’t offer advice or confer on cases—they do. But as Wang puts it, it’s about tone and respecting the abilities of the associate.

For those who argue there is little difference between a large group orthodontic practice and a dental service organization (DSO), Wang begs to differ. “When you go into those dental service situations, you are an employee to a corporation. That’s not to say that you’re not an employee when you are an associate [in a large group practice], but you are also a colleague. I think that’s an important difference to understand.”

What’s more, he points out, “There is less autonomy in a DSO because they have streamlined everything to the bottom line. In our practice, that’s not how it goes. We’re not ignorant of the bottom line, but at the same time we allow you to develop as an orthodontist. We want you to try things that you want to try.”

Wang is quick to add that it’s not a one-way street either. Working as a group means the senior doctors are able to learn as well. “That’s also what I like about our system and the way we have it set up. We learn from the new techniques and technologies every doctor brings to the table.”

When Wang, a graduate of Northwestern University Dental School, set out to find his first job, he admits he was looking for some type of partnership. He wanted the collegiality that comes with working with peers, and looking back on it, if that came with some built-in mentorship opportunities, he’s glad to have had it in those early years. Moreover, he liked the idea of working with others to create something bigger, all while balancing out each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

When Wang joined the practice as an associate, the practice had two well-established locations that had been in business over 20 years. He signed a 5-year contract, after which he would have the option to buy in as a full partner. Within 2 years of joining the practice, the group opened a third office to take advantage of a quickly developing area from which they were already drawing patients.

A fourth location was added when the existing private practice of one of the partners was brought into the fold. At the time, Wang, still in his 30s with student loans and a young family, was asked to work there 1 day a week because it was near where he lived. The fifth location came into play 3 years ago, as both practice resources and doctor time were available to create a long-term opportunity in another developing area. Wang ended up working at this location as well. As a result, he is now the only doctor in the practice who both works and has an ownership stake in all five offices. Wang is quick to point out, however, that he’s not tooting his own horn here. It simply came down to scheduling. “‘Hey, Larry. You got a day? Why don’t you work at this practice,’” he jokes.

As an associate, Wang had no financial obligations to the practice; he only had to work there. But that was never his mindset. He took ownership of the office from day one; and he says that is something he would advise any associate coming into a group practice to do.

“I didn’t take the attitude that I’m not an owner, so I can’t say anything; nor did I say, ‘There’s a problem. You’re the owner. You handle it.’ No, I’d say, ‘There’s a problem. How do you want me to handle it.’ I wasn’t hesitant to make suggestions or address issues. It was: This is my home. And I treated it as such. That makes a difference,” he says. “You walk in thinking if this goes down, I go down.”

And this is a mindset he wants to see in new associates. “I really am looking to see is this a person that can build my practice. Is this someone who can build upon what we already have? This is a big operation, but it needs to continuously move forward. I look for someone that has the personality to get out there and market the practice and take it to the next level.” And when that doctor gets out there in the community: “You are representing the Baltimore Orthodontic Group, not yourself.” After all, this is a team.

A key factor in the success of such a large practice is that team, says Wang—specifically the 55-member strong support staff. They provide the continuity and consistency. Each location has a core base of assistants; in addition, each location’s management remains consistent. Only a few clinical and front office staff float between locations. “You need that core. That’s one of the rules we learned early on. If you’re going to have different doctors, fine. But you have to have a consistent core group of office staff,” Wang says.

Wang credits the group’s staff with being able to adapt to the nuances and quirks of each doctor they work with, because it can be a different doctor every day. The core team is also critical to maintain continuity of care for the patients of each office.

Currently, Baltimore Orthodontic Group has three associates and three partners. While it is difficult to have an all-doctors meeting, Wang and his partners, Michael Riger, DMD, MS, and Kenneth Kyser, DDS, do meet to review staff, patient, and business issues. But, according to Wang, staff leadership (office managers, clinical coordinators, front desk coordinators, treatment coordinators, financial coordinators) is more important than these meetings when it comes to the day-to-day running of the practice. What’s more, protocols and scripting go a long way in creating order and success.

Noting that the words protocols and scripting are often thrown around in discussions about practice management, Wang contends they are vital to such a large practice.

“Consistent staff and patient management, consistent clinical protocols, consistent scripting so people are saying the same thing between five offices: That’s always a challenge. If you ask what is one of the things we’re always thinking about—that’s number one on our list,” he says. But once that protocol is established, Wang credits staff leadership with making sure it is implemented.

Another important factor in the success of the Baltimore Orthodontic Group, according to Wang, is the fact that four of the five offices are pediatric dentistry/orthodontic combo practices—but there is a caveat. The pediatric dentistry portion is a completely separate business. Financially, the two are not connected. Baltimore Orthodontic Group and the pediatric practices only share office space, specifically the waiting room and play areas.

“I take no credit for that decision, but it was a good one. This is a credit to the senior partners who had the foresight to see this as a good setup,” Wang says. “Look, it can only help you to be next door. It’s a mutually beneficial relationship, but the setup allows us to make business decisions independent of one another.”

Even as he sings the praises of the large group practice model, Wang is honest about the challenges. Change can be slow to implement. “Let’s say I’m at the [AAO Annual Session in San Diego] now, and I learn about this great new technique. Wednesday, I’m back in one office and I say, ‘I learned this great new technique. Let’s do it.’ The problem is I then have to go to every office and let them know about this new great technique. When you walk into this type of practice, you have to be patient. You cannot insist on saying, ‘I want to do this now.’ You have to let the other doctors and your team know what you want to start or change and allow things to develop,” he says.

For Wang, the best way to view this model is as a marriage. “Many years ago, someone said that to me when I talked about the kind of setup we have. And it’s absolutely right. There are ups and downs. There is compromise. You have to be prepared for that. We don’t always see eye to eye. But we’re willing to say I’ll give your way a try or you’ll say, you’ll give my way a try; or we reach the middle.”

Wang, who is a member of the cleft palate teams at both the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins, is an active volunteer in the leadership of the profession at state, constituent, and national levels. He has already served as president of both the Maryland State Society of Orthodontists and Middle Atlantic Society of Orthodontists. At the national level, he’s chaired the AAO’s Council on Information Technology, and is currently an AAO delegate and serving on the AAO task forces charged with rewriting the clinical practice guidelines and looking at workforce distribution. The latter seeks to gather data that will allow the association to get a handle on where new graduates are going when they finish their residency and what opportunities are available to them, and then provide the necessary resources to help them as they start their careers. His big project right now is as scientific co-chair helping to put together the doctors program for the 2018 AAO Annual Session in Washington, DC.

“This has been a great profession. It’s allowed me to do a lot for my family and myself. So I do believe in giving back to the profession in some capacity. I want to create something that is better for the next generation because it is getting tougher out there,” he says.

For those wondering if they should get involved with the different professional organizations, Wang says yes and stresses that it offers an incredible opportunity to see the profession on a larger scale.

“It forces you to be out there and to communicate with colleagues. You’re learning the good of what’s going on in your profession, but you’re also learning about the problems other doctors are having—and now you’re in a position to get the ball rolling to address that and to correct what you see.”

Wang refuses to see his fellow orthodontists as the competition—an important point to keep in mind when considering a large group practice. He fundamentally believes in collaboration. “With the challenges we are facing, that’s the way we need to go. We need to be a collaboration of like minds looking out for one another. In this competitive time for orthodontists, who is going to look out for you? That’s what I try to express to everybody. We’re the ones who have to look out for each other and our specialty.” OP