by Rich Smith

Clarence (Chip) Shelton, DDS, splits his time between orthodontics and jazz

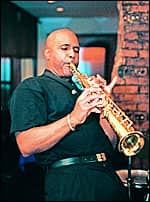

“I treat patients 2½ or 3 days a week so that I can have time to work as a jazz performer,” says Shelton, a soul-stirring flutist and occasional singer who also plays saxophone and piano to the delight of crowds sometimes numbering in the thousands. “I’m not in a situation where I’ve got a day job and an avocation on the side—these are two, coequal careers.”

While the New York-based Shelton might not be a household name like Louis Armstrong or Kenny G, he has achieved impressive commercial success, including recording contracts and performance tours. “A question I’m often asked is, ‘If I’m doing so great in the music biz, why not give up orthodontics in order to concentrate on playing?’ ” he wonders rhetorically. “The answer is economics.

“Orthodontics, it’s a sure thing. It guarantees me and my family a comfortable life. Music, on the other hand, it has its ups and downs. One day you’re hot, the next you’re not. You could be having the best and biggest success of your life this year, but, then, next year, you’ve vanished from the charts and no one remembers you. You can’t feed a family and keep a roof over your heads on a basis like that.

“Besides, I wouldn’t be happy doing music only. I need to do orthodontics just as much as I need to play music. I love orthodontics, and I have a real flair for it. After 34 years in practice, it’s part of who I am. It’s incredibly rewarding to be in this profession.”

Picking Up the Tempo

Apart from the novelty of his successful career in music, Shelton’s practice is distinct in the Manhattan market because of its strong emphasis on aesthetic options, such as clear braces and lingual orthodontics.

“Being able to offer such options has brought to us a sizable number of adult patients,” he says, noting that 55% of his patients are grown-ups. “These are people who otherwise would never have considered orthodontics for themselves because of concerns about the impact on their careers or social standing by having to wear conventional braces for a year or two. Quite a few of them make their living in front of a camera.”

Shelton also stands apart from the crowd by scheduling fewer patients each day so that he can spend more time with those he does see. In this way, he is able to accomplish more at every visit and, consequently, offer shorter treatment times. “Early in my career, I myself wore braces, and so did my office manager,” he says. “Our experiences with that convinced us that patients would really appreciate having to wear braces for the fewest number of months possible. So, in the late 1980s, we stopped using the system of allotting x minutes of chairtime per patient and then, when that time limit would be reached, halting the work at whatever point we happened to be and then, at the next visit, picking up where we left off.

“Instead, we decided to start spending however much chairtime was needed with the patient to accomplish all of the tasks necessary during that particular visit. This is how we’re able to finish treatment in 12.8 months on average, and without having to resort to increased pressure.”

Incidentally, it was this ability to deliver faster treatment results that inspired the name of the practice, Accelerated Orthodontics, which has been the name of Shelton’s practice since about 1994.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Music in the Background

Located adjacent to the northwest side of Central Park, Shelton’s office features a large reception area; a sequestered consult room; and a semiprivate section where exams are conducted, impressions are made, and a limited amount of treatment is performed. Most of the casework takes place in a three-chair, open-bay operatory. Further back is Shelton’s private office, which includes a shower so that he can freshen up before seeing patients after a brisk workout in the park or at a nearby gym.

Shelton says staying physically fit is of paramount importance to a hyper-busy person like himself; athleticism results in increased levels of on-the-job and on-stage energy and endurance.

Shelton has integrated his music into the orthodontic office, but in a strictly low-key manner. In one corner of the reception area, for example, is a modest display board featuring a calendar of coming Chip Shelton gigs along with a few write-ups and photos of his most recent performances (the newest set culled from an appearance at the Cape May Jazz Festival). Meanwhile, the piped-in music continually playing in the background usually includes only a few cuts of Shelton on his own pipes.

“We have a CD changer that plays a rotation of 60 different albums, and a couple of mine are in the mix,” he says, adding that Chip Shelton CDs can be purchased in the office, but, “We don’t inundate patients with my music; their exposure to it is limited. By the same token, though, if anyone is intrigued by it, we make available the opportunities for them to learn more about it.”

Patients don’t often choose Shelton as their orthodontist in response to his musical status. In fact, most haven’t an inkling that he is anything other than an orthodontist at the time they first walk into his office. However, once they make the discovery that he’s a professional jazz flutist, it adds an entirely new dimension to the relationship. “A lot of them are pretty impressed, that’s for sure,” he says.

No Staged Conversations

A few patients take the opposite route to becoming patients. They begin purely as fans of musician Chip Shelton, oblivious to the life he leads as a practicing orthodontist.

“It’s much, much easier to incorporate music into my orthodontic practice than it is to incorporate my orthodontic practice from the stage. People in an audience just have a lot of trouble seeing the connection,” he says. “Usually, the way the orthodontics part comes up at a gig or an event is after the show, when someone from the audience will come up to me to say how much they enjoyed the performance. We’ll talk about the music, then drift into other topics, and, sometimes, the conversation ends up focused on teeth.”

Of course, it’s not always entirely by happenstance that the chatter heads off in that particular direction. Shelton occasionally leads it there. “I’m a believer in the value of networking,” he explains.

But no matter how it ultimately is revealed that Shelton straightens teeth for a living, he comes prepared with plenty of business cards. Says Shelton, “The case I carry those cards in has two sides: one has my musician business cards, the other has my orthodontist business cards.”

Although an orthodontic presentation from the stage doesn’t normally sell with audiences who’ve come to groove on the torrid sounds of a smoldering woodwind, there are exceptions. “A couple of times we put on shows that were intended expressly to market orthodontics. These events were artistically satisfying, met with some business success, and audiences knew going in that there was an orthodontics connection.” Shelton explains that these performances, sponsored by a vendor of orthodontic supplies, took place in a major jazz club that featured a big-screen overhead video monitor upon which was continually displayed information about orthodontics while his office staffers distributed literature about the practice.

Tuning Up

The coal-mining country of West Virginia, where Shelton was born and spent his preteen years, isn’t exactly celebrated as a mecca of jazz. Neither is Dayton, the Ohio city that became Shelton’s home after his family moved there when he was 12. Nevertheless, it was in both those locales that Shelton became steeped in the traditions of Dixieland, ragtime, bop, swing, jive, and a whole host of other forms of modern American jazz.

Says Shelton, “My father, a music lover himself, taught me drums, ukulele, and clarinet when I was real young.” He also learned piano and saxophone, sang in the school choir, and was a star pupil at the local dance academy. At one point, Shelton even won a community televised talent show competition. (No, it wasn’t called Dayton Idol.)

In the sixth grade, Shelton decided he also wanted to become a dentist. “My school had arranged for a dentist who operated a mobile clinic to stop by and provide free exams for all the kids.” Shelton’s eyes opened wide with fascination as he stepped inside the trailer and caught sight of the arrayed equipment. “This looked like it had to be the coolest job on earth,” he remembers thinking. Dentistry also appealed to young Shelton for other reasons as well. “I had an aptitude for science and I enjoyed tinkering, both of which made me well-suited for this profession,” he tells.

After completing his undergraduate studies, Shelton went on to Howard University for dental schooling. A top-of-his-class student, Shelton had his pick of institutions for orthodontic training, and he chose Columbia University. “Columbia offered a terrific orthodontic program, and,” he says, “being in New York City made it possible for me to continue developing my music skills under the tutelage of some of the great names in jazz.” Those names included Bill Barron, James Moody, Hank Mobley, Irene Reid, Jimmy Ponder, and Frank Foster.

In 1972, with his training completed, Shelton briefly went to work for various hospitals around the city and began to entertain the idea of starting a private practice. Later that same year, he espied across the street from his flat on the corner of Central Park West and 97th Street a sign indicating an office space for lease. “It was affordable, with a generous amount of square footage by Manhattan standards—1,500 square feet. So I leased it and set up shop there. I’ve been in that same location ever since,” he says. He has since added a satellite in New Rochelle, at which he today sees patients 2 days out of every month.

In the Swing of Things

Clearly, Shelton is a busy individual. As if he didn’t have enough on his plate already, Shelton also spends 2 days per month teaching orthodontic residents at St Barnabas Hospital and at Montefiore Medical Center, both located in The Bronx. “I’m the head of the light-pressure technique department,” he says. “That once meant teaching Begg orthodontic technique, but it later segued into Tip-edge and now is getting into self-ligation with its low-friction, light-pressure advantages.”

Shelton has also coauthored a number of research papers. The most recent of which appeared last year in the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics (2005;128:292–298). In that article, lead investigator Shelton and his colleagues compared clear aligners and fixed braces and found that fixed braces “clearly had more precise finishing and results when subjected to minute measurements, but labial-lingual movements that were surprisingly efficient and well-accomplished by [aligners]” were “very comparable to those accomplished with fixed appliances,” he recounts.

“Another surprise was that the time frame for completion of treatment was similar for both fixed braces and [aligners]. We went into the project thinking that [aligners] would take significantly longer, but, as we learned, such was not the case.”

For the past couple of years, Shelton has been assisted in practice by an associate orthodontist, who, unfortunately, is moving on to launch an office of his own in another part of the state. The pending vacancy will have Shelton looking for a replacement, someone almost certain to be drawn from among the residents Shelton teaches.

The practice, meanwhile, is continuing to grow, thanks in part to Shelton’s commitment to stay on the cutting edge by mastering new techniques that gel nicely with his niche. However, Shelton is nearing retirement age, so he is beginning to formulate an exit strategy. But that will apply only to orthodontic practice. As for music, Shelton plans to keep that aspect of his life going until he can no longer purse his lips, adroitly glide his fingers over a set of valves, and muster enough force of wind to form audible notes. Who knows? He could still be going strong at 100. By then, he might even be so successful that his warm-up act is Kenny G.

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products.

| A Jazz Odyssey If it can be classified as jazz, Clarence (Chip) Shelton, DDS, almost certainly plays it or composes and arranges it. Swing, shuffle, modal, blues, samba, bossa, Latin, 6/8, waltz, jazz, funk/rock, ballad, calypso, reggae: He is a maestro of them all.

Shelton’s musical fortunes had been building since before entering college, but his career as a performer really took off in the mid-1980s, more than a decade after launching his orthodontic practice. “In 1987, I devoted myself to advanced studies of sax and flute, first with Broadway musician Ken Adams and then with woodwind innovator John Purcell of World Saxophone Quartet fame,” Shelton says. From 1988 to 1990, he attended Manhattan School of Music full-time, majoring in jazz flute even while continuing to build a vibrant orthodontic practice. Shelton also continued private study with world-renowned instructors, one of whom is considered the dean of American flutists: Julius Baker, formerly of New York’s famous Julliard School. In the early 1990s, Shelton honed his skills in performance alongside a number of prominent artists of the jazz scene. He then caught the notice of veteran drummer-turned-record-producer Kenny Mead, who helped Shelton’s career scale new heights, culminating in the first of several album deals, as well as live gigs in the company of jazz luminaries Louis Hayes, Dick Griffin, Joe Lee Wilson, Roy Ayers, Bob Baldwin, Ted Curson, Antonio Hart, Ron Carter, Onaje Allan Gumbs, Roy Meriwether, John Hicks, Calvin Hill, Ryo Kawasaki, Guillerme Franco, Lynn Seaton, and more. In the mid-1990s, Shelton formed a band that featured 10 of the Big Apple’s top flutists and a five-piece rhythm section, calling itself the World Flute Orchestra. He later put together a smaller group by the name of the Jazz Flutet. Shelton (and his band) today play mostly at clubs, concert halls, and jazz festivals along the Eastern Seaboard. He’s been onstage at Madison Square Garden, the Apollo Theater, and a host of other well-known New York venues. Occasionally, he lands engagements outside the area. His farthest travels have taken him to Germany and Egypt. At both stops, his performances were recorded, and Shelton indicates they will be released as albums in the near future. —RS |

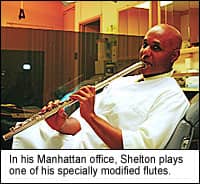

Shelton’s preferred instruments are a concert flute in C; a B-flat flute d’amor; a bass flute; a contra-bass flute; an alto flute in G; any number of ethnic wood flutes; and every parade-lover’s favorite, the piccolo. The concert flute in C and the B-flat flute d’amor he owns have been custom-fitted to be blown into from the end, much like a saxophone, rather than from the side, as is conventional with flutes. Shelton says he likes the way these modified instruments play; plus, they serve as cool-looking trademarks.

Shelton’s preferred instruments are a concert flute in C; a B-flat flute d’amor; a bass flute; a contra-bass flute; an alto flute in G; any number of ethnic wood flutes; and every parade-lover’s favorite, the piccolo. The concert flute in C and the B-flat flute d’amor he owns have been custom-fitted to be blown into from the end, much like a saxophone, rather than from the side, as is conventional with flutes. Shelton says he likes the way these modified instruments play; plus, they serve as cool-looking trademarks.