by Clark D. Colville, DDS, MS; Ken Fischer, DDS; and David E. Paquette, DDS, MS, MSD

Using attachments to improve clear aligner therapy

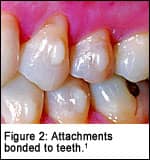

During orthodontic treatment with clear aligners, the aligner sequence works by repositioning the teeth according to the movements programmed into each individual appliance. Attachments are composite shapes bonded to tooth surfaces to enhance the interaction between the aligner and the teeth. On the 3D digital model, attachments are represented as red shapes that translate into an equivalent geometry built into the aligner. Clinically, the attachments are created by bonding filled dental composite on the target teeth using an aligner-like template as a positioning guide.

Attachments are currently available in two shapes: ellipsoid and rectangular. The position, orientation, size, and thickness can be adjusted to accommodate different clinicians’ needs.2 How to best use attachments is now the subject of many orthodontic discussions, and presented here are three individual experts’ opinions on attachments.

As a technique with a less-than-10-year history, the biomechanics of using clear aligners and their most efficient and effective application is constantly under clinical investigation and revision. Early on in the use of aligners, it became apparent that although most teeth stayed seated in the aligners as treatment progressed, sometimes after a period of time as the aligners were changed out, teeth would not undergo the prescribed movements and therefore would no longer be fully seated in the aligners. To increase retention and thereby facilitate the tracking of aligners, composite embellishments called attachments were placed on tooth surfaces.

These attachments serve two basic purposes. The first and most important purpose is retention. Experience has shown that tooth anatomy and patient compliance are the two biggest single factors for treatment success with aligners. Patients with long clinical crowns are undoubtedly very straightforward to treat because of the great retention and large amount of tooth surface for the aligners to exert force against. As the size of the clinical crowns decreases, the need for attachments to offset the smaller surface area in contact with the aligners increases. The second purpose is to provide a surface upon which to exert additional force and, in doing so, to create a moment arm for biomechanical advantage. It appears as though many times, the greater benefit of this “force-directed surface” is actually aligner retention so that the side effect of force application is not aligner displacement.

|

The size, shape, and placement of attachments have undergone a considerable evolution in a relatively short period of time. The first attachments were ellipsoid in shape and looked like a hemisected football bonded to the tooth surface. These attachments were somewhat effective, but for movements that required more defined root movements such as tipping or torquing, the results were less than ideal. Rectangular curved root tipper (CRT) attachments seemed to solve some of the clinical issues. In my practice, we tried attachments in complex shapes such as x’s or L’s, but they did not really seem to be any more effective than the rectangular attachments, and they also tended to not track as effectively.

Rectangular CRT attachments provide a straight surface against which the aligner can apply force. I have found that the vertically oriented CRT attachments are most effective for root tipping and root paralleling, whereas horizontally oriented ones are most effective for vertical and root torquing movements.

The disadvantage of rectangular-shaped attachments is that they present an all-or-none engagement phenomenon. In other words, if the attachment is not seated correctly in the aligner bubble, not only does the tooth not track properly, it is moved to a place other than the intended location. It has been suggested that the effective distance of the attachment to the gingival edge of the aligner should be at least 1.5 mm to avoid undesirable flexing of the aligner material. Unfortunately, vertical attachments often end up with the gingival aspect very close to the gingival edge of the aligner so that the aligner inevitably ends up flexing against the attachment. Vertical attachments also have the disadvantage that there is a very small surface of the attachment to aid in aligner retention.

By placing the rectangular attachments in a horizontal orientation, much greater aligner retention can be achieved. As horizontal attachments are moved closer to the occlusal/incisal surface, the amount of retention is increased because the aligners’ flexibility decreases correspondingly. In fact, when horizontal attachments are placed within 1 or 2 mm of the occlusal surface, there is essentially a snap fit to the aligner/attachment interface. However, this makes it difficult for the patient to insert his or her aligners due to the edge being perpendicular to the direction of aligner insertion and removal. To facilitate aligner insertion, a high-speed handpiece may be used for beveling the incisal aspect of the attachments once they are bonded in place and prior to aligner delivery.

Having the technician virtually rotate the horizontal attachment “into” the tooth surface produces the same effect and saves clinical time for the orthodontist. This “beveled” attachment is placed as close as is practical to the occlusal/incisal surface for maximum retention. It is designed so that the prominence from the tooth surface is 1 mm and the beveled edge at the incisal aspect has a roughly 0.25-mm ledge, as opposed to a surface that is feathered into the tooth surface. This small ledge provides a defined finish line when placing the attachments clinically and avoids excess material flash around the attachment that would require additional chairtime to clean up.

Ken Fischer, DDS

With traditional braces, we have a more direct transfer of pressure from the appliance system to the tooth. The use of attachments with aligners improves the manner by which the aligner can hold on to each tooth to deliver the pressure needed to move teeth more effectively. Therefore, the design, placement, and staging of various attachments throughout an aligner case are very important for successful aligner treatment.

I have found that several modified standard attachments have been particularly effective in my practice. These are:

? Double horizontal rectangular (DHR) attachments;

? Beveled rectangular (BR) attachments; and

? Inverted T attachments.

The DHR has worked well on the buccal surface of molars for retention and axial control. I have used an inverted T attachment on cuspids for optimal control of movements in multiple planes of space, especially during retraction for space closure. I have used BR attachments to allow attachments to better snap into place and to ease the patient’s efforts to place and remove aligners with multiple attachments.

Clark D. Colville, DDS, MS

While all the answers are not known at this time, my clinical experience has demonstrated some clear indications for attachment placement in my office.

Retention attachments are placed on specific teeth to ensure that each aligner has a “snap” fit over each arch so that movements can be fully expressed. Attachments to facilitate difficult movement for aligners are placed on individual teeth to provide purchase points to either counteract undesirable movement such as unexpected intrusion, or to provide surface area on which the aligner can produce sufficient moments of force in situations such as rotation of teeth with round facial and lingual surfaces.

In the following table, I have listed the attachments we have used for common difficult aligner movements experienced.

The most commonly used attachment type for the majority of circumstances in my office is the horizontal beveled attachment with the following dimensions: height 3, 4, or 5 mm x width 2 mm x thickness 1 mm. Since the beveled attachment is not yet listed as a standard option, a description must be given to the technician to create a beveled attachment using a standard rectangular one.

The advantages of this attachment are the following:

? It is barely visible (due to diffraction of the light at the tooth surface);

? It makes it easier to insert and remove aligners (compared to rectangular attachments); and

? The attachment is “dynamic.”

Rectangular attachments require complete seating of the aligner to engage the attachment, because the emergence angle of the tooth-to-attachment interface is a right angle. The beveled attachment, however, is more forgiving, because the space in the aligner only needs to pass beyond the peak of the beveled attachment. The emergence angle of the beveled attachment being greater than 90° enables the tooth to work its way into the aligner over the first few hours of wearing each new aligner (assuming the velocity is not greater than the ability of the periodontal ligament to compress or extend over the peak of the attachment). It is critical to ensure that teeth continue to fully seat into the aligner and are not deflected away from the aligner if there is less than a 100% seating at the initial placement of a new aligner.

It should be noted that an ellipsoid attachment that is 1 mm thick also has many of the same advantages listed above. In fact, a clinical study by Wheeler at the University of Florida appeared to indicate that a 1 mm ellipsoid attachment performed better than the other types of attachments in the study. Although the horizontal beveled attachment was not evaluated in that study, it is thought to be more effective due to the increased surface area when compared to the ellipsoid attachment.

In summary, attachment design and placement is critical for treatment success with aligner systems. The current use of horizontal beveled attachments in my practice has proved to be very effective at ensuring better aligner engagement to the teeth.

Clark D. Colville, DDS, MS, is in private practice in Seguin, Tex. He is an assistant clinical professor in the department of orthodontics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. He can be reached at [email protected].

Ken Fischer, DDS, is in private practice in Villa Park, Calif. He is a guest lecturer at UCLA and Loma Linda University. He can be reached at [email protected].

David Paquette, DDS, MS, MSD, is in private practice in Charlotte, NC. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics. He can be reached at [email protected].

References

1. Tuncay OC. The Invisalign system. Quintessence Dent Technol. 2006;10:92–93.

2. Invisalign attachment protocol. Available at: www.invisaligncec.com/consistent/pdfs/AttachmentProtocol0603.pdf Accessed August 17, 2006.