by Rich Smith

World-class athlete Frederick L. Johnston, DDS, keeps pace with a thriving solo practice

Not bad for a solo-practice start-up. The secret of its swift climb is found in the philosophy of owner and gold-medalist track champion Frederick L. Johnston, DDS. In distilled form, it comes down to this: Be fleet of foot, and soon you’ll be footing around for a bigger fleet of chairs to handle the crush of patients beating a path to your door.

“Currently, I’m doing between 20 and 25 new-patient starts per month,” says Johnston. “I figure we’ll be up around 70 or 80 a month before long.”

You can probably make book on that, because Johnston is no stranger to runaway success. Previously, he was a partner in a winning multispecialty dental group. Based in a stylish, 11,000-sq-ft Fremont, Calif, office, it was one of the state’s most prolific such practices, generating revenues of about $10 million a year. That income came mainly from insurance reimbursements.

“Our group was successful for many reasons, but among the most central being our decision to concentrate on insurance business,” says Johnston, a board-certified practitioner subspecialized in orthognathic surgery and treatment of cleft lip and cleft palate. “We had entered into agreements with payors to send their insureds to our group exclusively. This was an attractive arrangement for them because we offered all the specialties, including periodontics, pediadontics, endodontics, and oral surgery. They saw in us one-stop convenience for patients and, for themselves, easier administration of claims.”

Johnston’s former group also hit the heights it did because he and his partners elected to entrust the business side of their combined practices to a professional administrator. “We were freed to focus on clinical matters, which resulted in us being able to deliver excellent quality of care,” he says.

Reaching Out to the Community

Particularly discomfiting to Johnston was the new owners’ sharp scaling back of the marketing budget. “They stopped educating the community about orthodontics, and that, of course, had an adverse impact on my practice,” he says.

Today, Johnston has no shortage of eager patients, thanks in part to his choice of location: He’s set up shop in a place where new homes and businesses are sprouting like California poppies after a spring rain.

“The population has increased so much that the city’s about to open a new middle school,” he enthuses.

Johnston’s office is located in a 1,600-sq-ft space leased at an upscale shopping center frequented by young families. The office’s airy interior design features slate flooring, antique furnishings in the waiting room, and shelf upon shelf of sports memorabilia. “I’ve never had my collection of sports memorabilia appraised, but I know that, to me at least, it’s priceless,” says Johnston.

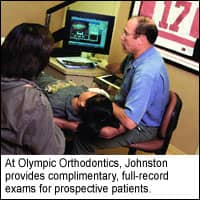

Not many people admit to becoming patients of his just because they like gazing at the sports memorabilia. Usually, they pick Johnston for his professionalism tempered by kindness, perhaps best exemplified by his standing offer to provide complimentary, full-record exams for prospective new patients (the records alone are a $500 value). “It’s a way to acquaint patients and parents with my practice without putting pressure on them,” he says. “If they decide they don’t like the office, they don’t have to commit to anything, and it’s cost them nothing.”

In reality, very few prospects balk. “My practice has grown dramatically using this strategy. One of the things people like about it is they don’t have to come in for two additional appointments before the braces are put on. Because I’ve done the full-records exam and consultation on the initial, no-charge visit, the banding is performed the very next time they come into the office.”

Not all patients are started so quickly. Johnston goes more slowly with cases involving surgery or cleft lip and cleft palate owing to the need for more education-oriented communication.

Won’t Tread Water

Until he started Olympic Orthodontics, Johnston considered himself a low-tech kind of practitioner. But glance around his office today, and you’ll blow your mind trying to tally up all the gigabytes of disk-drive capacity and RAM contained in the computers and digital-imaging systems installed here, there, and everywhere.

“My office uses an orthodontics-specific system that allows us to be fully paperless and filmless,” he says. “Patients arriving at the office check in by computer at the front desk; the computer then prefetches their records—including images—for display at the chair, so all the information we need is right at our fingertips the instant the patient sits down.”

It wasn’t easy for Johnston to switch from being computer-averse to computer-empowered almost overnight. “I was accustomed to having the charts on paper, right in my hands. I wasn’t eager to convert,” he confesses.

Yet, convert he did after the office supervisor he’d newly hired persuaded him to go electronic. “She came from an office that was extensively computerized,” he says. “She had good ideas about how we could incorporate computers in my practice, and made a good case for that.”

Briefly, Johnston toyed with letting the supervisor and the rest of the staff function digitally while he himself continued to live in an analog world. He snapped out of that delusion once it occurred to him that to have an office half computerized and half paper-based would be like having one foot in an untethered rowboat and the other on the dock. Before he could say, “This is an untenable position,” there’d be the sound of a big kersplash and the sorry sight of an orthodontist treading water.

Installing his extensive computerization wasn’t cheap, however. It cost Johnston $40,000—but was worth every penny, he insists.

“With the fully high-tech environment I’ve created, we’re extremely productive,” he says. “In the old days, the most number of patients I could see in a day would be 50. Now, because I and my staff are so much more efficient, I can see as many as 70 a day, easily.”

Computerization also allows Johnston to replicate the success formula developed by his former group.

“I’ve gotten Olympic Orthodontics off to a great start by catering to HMO and PPO plans, which nowadays is something you almost have to be paperless in order to be capable of doing well,” he says. “Electronic claims submission, electronic documentation; that’s what the insurance companies want. I’m one of the few orthodontists around here who accepts insurance, and as a result I’m taking the market by storm.”

Over the Hurdles

Before becoming an orthodontist, Johnston’s prospects of taking anything by storm seemed bleak. Born of Hispanic parents in a hardscrabble neighborhood of Mercedes, Tex, Johnston grew up economically disadvantaged. Accordingly, a university education for him would have been beyond reach were it not for the fact that he was a gifted young athlete.

“In 1968, I was national junior-college champion in high hurdles, with a record time of 14.1 seconds—a real triumph for me because my times prior to that weren’t all that good. I was definitely the underdog at that particular meet, but I came from behind and won.”

The athletic prowess that enabled Johnston to so swiftly clear those hurdles gained him a sports scholarship to Southwest Texas State University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree before moving on to dental school at UCLA. (In 1969, his plans to enroll at Southwest Texas State University had to be sidelined for 2 years while he served his country as a dental technician in the Army.)

It was while at UCLA School of Dentistry that Johnston decided to specialize in orthodontics.

“The man who became my mentor, Spiro Chaconas [DDS, then-chairman of the UCLA orthodontics department], pointed out to me that, in orthodontics, treatment didn’t cause trauma to patients and you could get very good results. That really appealed to me. I also liked that orthodontics could be lucrative.”

From UCLA, Johnston headed north to the University of California, San Francisco for orthodontic training. In 1979, fresh out of that program, he found employment in Fremont, working alongside three dentists who, with Johnston, would shortly thereafter form the wildly successful group that he left in 2004.

Prior to joining the dentists, Johnston considered returning to Texas to practice. But he’d married a Bay Area woman, so that was where he remained. He chose Fremont because it was a city on the cusp of explosive growth.

Balance of Power

In addition to his role as a volunteer coach (see sidebar) and his participation in world amateur track, Johnston also plays the part of family man. He has a daughter, 22, and a son, 20 (who happens to be a 6-foot, 4-inch southpaw pitcher for a local college baseball team). “I try to be a number one dad,” Johnston says. “I approach parenting the same way I approach track: I put my whole heart into it.”

Still, with so many irons in the fire, the only way busy Johnston can keep a proper balance is through good planning of his time, a task he leaves to his office manager, the official keeper of the schedule.

“She develops my daily schedule in such a way that I’m able to get all my work done and still have ample time for my outside interests,” Johnston offers. “A big help with that is the extensive computerization we have here.”

The efficiencies gained through computerization allow Johnston to see a full week’s worth of cases in 31/2 days (the office is open Monday through Wednesday and on Thursday afternoons). He’s supported by a staff of five, but looks forward to the day when growth will compel him to hire more people, including an associate orthodontist.

“Whoever I bring aboard,” says Johnston, “he or she will have to possess the same philosophies as mine.”

That means the newcomer had better be prepared for the run of his life.

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products.

Life in the Fast Lane

Sports memorabilia is a key element of the office decor at Olympic Orthodontics. Figuring prominently in the collection are artifacts, autographs, and photos of superstars such as Mohammed Ali, Kobe Bryant, and Barry Bonds.

“I’m a big Dallas Cowboys fan, too, so I’ve got all kinds of Troy Aikman and Emmitt Smith items,” Johnston adds.

As impressive as those memorabilia are, the crown jewel of the collection remains the gold medal Johnston himself captured for winning the 2001 World Masters championship in high hurdles, with a time of 14.9 seconds.

“I cherish this medal,” he says, “for the reason that it confirms for me that I’m an elite, world-class athlete.”

Taking the gold that day in Brisbane, Australia, gained Johnston considerable attention back home in Dublin—and, he says, it even helped make him a better orthodontist.

“The training, the competitiveness of the sport, the pushing myself to the limits of endurance—these have all equipped me to concentrate my mind and energies on making my practice a truly winning practice,” Johnston says. “I make sure everything in my office is first class; I don’t accept anything that’s second rate.”

Athletics, he insists, also taught him to be a leader.

“People have respect for leaders, and want to imitate the things you do as a leader in order for themselves to become winners in the areas of life that are important to them,” he says. This plays out in his practice when patients are willing to “pay closer attention to what I tell them about compliance and hygiene technique.”

The World Masters gold medal Johnston proudly displays is joined by about 500 other laurels he has won, beginning in grade school. “I’ve been competing right up to the present day,” he says.

Johnston was at the peak of his youthful athletic prowess in 1975 when he attempted to qualify for the US Olympic decathlon team. He nearly made it, too, having scored sufficient points in each of nine track-and-field events. But the tenth event was his undoing.

“It was pole vaulting. I was terrible at it.” The reason? “I had a fear of heights,” he reveals.

These days, when not competing, Johnston coaches the students on the track team at nearby Foothill High School.

The drawback to the coaching gig isn’t the time it takes (about 10 hours a week) so much as the energy it eats up.

“I go to the track meets with the kids and, after a long day of being in the sun and wind, I come back home totally drained,” he says. “I’m so physically exhausted, I often can’t do my own track workout the next day.”

Johnston conducts his personal training regimen every other day. Mostly, it consists of treadmilling, a little light running and some easy hurdles. But on one day out of every week, it’s full-bore, pedal-to-the-metal stuff.

“Because of my age,” he says, “I can’t go real heavy on the training each and every time.”

But train he must. Johnston faces his next big contest in August, when the National Masters championships are held in Honolulu. Later that same month, he’ll be competing for world honors in San Sebastian, Spain. Both times he’s entered in the 100-meter hurdles. Johnston feels confident he’ll do well.

“I expect to be in the top three,” he predicts.

—RS