by Rich Smith

Lisa Alvetro, DDS, MSD, uses teamwork to build a thriving practice and an orphanage in Africa

|

Everyone loves a worthy cause. In the Sidney, Ohio, orthodontic practice of Lisa Alvetro, DDS, MSD, the worthy cause that most warms the hearts of patients—and the community—is an orphanage that will shelter 45 children in the remote village of Tarime, Tanzania.

Alvetro is the primary mover and shaker behind this endeavor, and she is helping to pay for construction out of her own pocket. She also invites patients to contribute, and many have responded to that call. “I’ve been thrilled with the way my patients, friends, and the community have joined in,” she says.

Building Angel House

PRACTICE PROFILE |

|

|

Name: |

Lisa Alvetro, DDS, MSD Inc |

|

Location: |

Sidney, Ohio |

|

Owner: |

Lisa Alvetro, DDS, MSD |

|

Specialty: |

Orthodontics |

|

Years in Practice: |

15 |

|

Patients per day: |

120 |

|

Starts per year: |

680 |

|

Days worked per week: |

3 to 4 |

|

Office square footage: |

9,000 |

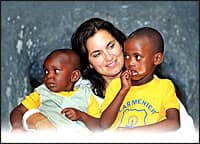

Alvetro became involved with the Tanzanian orphanage as a result of her participation in a dental mission trip to Africa. In 2001, she became friends with members of Grassroots, a New Carlisle, Ohio-based humanitarian organization. This group had been working with the people of Tarime, a Tanzanian village located between the Serengeti plain and Lake Victoria.

Persuaded of the worthiness of those efforts, Alvetro began contributing to Grassroots, which led to an invitation to visit the village. She arranged for Grassroots to reserve space in one of its Tarime-bound cargo containers so that she could pack enough equipment and supplies to allow her and a handful of dental colleagues to establish a clinic there.

Not long after setting up shop in Tarime, Alvetro discovered that many of the young patients coming to the clinic were orphans living in hardscrabble facilities lacking running water or basic sanitation. “We realized we had to provide an actual home for these kids,” she says. “Grassroots tried to do that, but couldn’t get any traction because they lacked on-site presence. They just didn’t have the people in place who could manage such a project on a day-to-day basis.”

Fortunately, Alvetro’s circle of contacts included an important Tanzanian official. At Alvetro’s behest, he was able to recruit the right people locally and get the ball rolling. Now, at last, the orphanage is under construction. As of mid-November, the foundation was laid, and workers were preparing to erect the walls.

“The people from Grassroots are still involved, but they’ve asked me to take the lead on this project,” Alvetro says. “In addition to obtaining government cooperation, my role has been to make sure the work crews in Tarime are getting the job done. I stay apprised of the construction progress through almost daily e-mails the orphanage staff sends me. It’s still a little hard to get used to the idea that, in a place with no indoor plumbing, they can still access the Internet.”

As the primary fund-raiser for the Tanzanian orphanage project, Alvetro contributes cash out of pocket plus the sums she is paid for lecturing on behalf of St Paul, Minn-based 3M Unitek. Additionally, she has devised ways for her patients in Sidney, Ohio, to chip in. For example, those who request teeth bleaching after removal of their braces can designate that the fee be donated in their name to the orphanage.

|

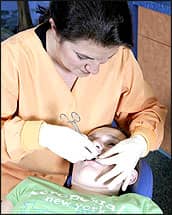

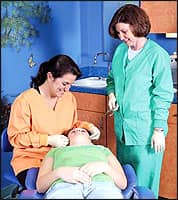

| Alvetro and clinical assistant Pam Kinninger are all smiles with Kathryn Rossman, one of the 120patients their office sees on a typical day. |

Although completion remains about a year away, the orphanage already has a name—Angel House. And, once the kids move into it, Alvetro says she would like to commence work on a school for them. “The village of Tarime has a government-operated school, but it’s severely overcrowded and underequipped—the student-teacher ratio is about 70 to 1, and the only supplies the students have is a classroom chalkboard,” she says. “The school we’d like to build would have a much more appropriate student-teacher ratio, as well as actual textbooks and writing materials. My hope is that improved education will, in time, help the people of Tarime and other villages in the region build better lives for themselves, and no longer be so dependent on help from the outside.”

Yet help is what Alvetro is all about. Put the pieces together and you have an orthodontist with an unusually big heart. Her patients know that. And so do the appreciative people of Sidney, Ohio.

Settling in Sidney

The town of Sidney—about 80 miles northwest of Columbus—is a good place to practice orthodontics. With a youngish population of approximately 20,000, it has more than a dozen private and public primary and secondary schools. Median household income is about $38,000.

|

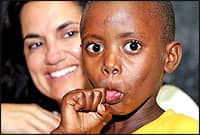

| Alvetro became involved with the Tanzanian orphanage as a result of her participation in a dental mission trip to Africa. She is now the primary fund-raiser for the project. |

Alvetro is not originally from Sidney, although she now lives there with her husband, Tom (a state civil engineer), and their three children—Kathryn (13), Michael (5), and David (4). Alvetro was born in New York (Long Island, to be precise) and grew up in the small northeastern Ohio town of Courtland. She moved to Sidney in 1993 after signing on as an associate in an established practice there, the one she ultimately purchased from its retiring founder.

Alvetro joined that practice after she earned her dental credential from Ohio State University, Columbus, and completed her orthodontic residency at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, where to this day she serves as a member of its faculty and teaches practice management.

In addition to these teaching duties, Alvetro frequently lectures throughout the United States on a variety of topics, including Class II correction by means of a fixed, functional appliance from 3M Unitek, the Forsus™ Fatigue Resistant Device. “I’m supportive of this product because I’ve found it to be an easy, efficient, and comfortable solution for severe Class II conditions, one that requires very little in the way of patient compliance,” she says. “I’ve also recently started talking about 3M Unitek’s self-ligating brackets for much the same reasons.”

Whether she’s in the office or away on the lecture circuit, the openness of Alvetro’s management style engenders a strong sense of team spirit among her employees. Alvetro capitalizes on that by turning over to the staff responsibility for everything from day-to-day operations all the way up to strategic planning, while she concentrates on clinical activities.

“I may be the CEO of this office,” she says, “but my team runs the show.”

As a team, the staff works hard. Accordingly, Alvetro tries to reward their devotion to duty by arranging the schedule so that it includes a number of extended weekends. “If we have a Friday off because of a national holiday or some other special circumstance, then I like to keep the office closed until that coming Tuesday to allow the staff to have a good, solid, 4-day break,” she says.

Cultivating Committees

Seventeen individuals compose Alvetro’s staff. Each serves on at least one practice decision-making committee. “There are committees specific to marketing, finance, facilities, scheduling, and so forth,” she explains, adding that they also are tasked with identifying practice strengths and weaknesses and then figuring out ways to leverage the positives and ameliorate the negatives. “The committees work out an action plan and then get everybody else in the office on board.”

|

Almost nothing is beyond the purview of the committees. Even the 9,000-square-foot building that has housed Alvetro’s office since 2003 was constructed under committee oversight. “Prior to that, we were in a leased space of only 3,400 square feet—too little room for us,” she says. “Also, that building was not being maintained by the owner in a way that properly represented to the world who we were—a quality, friendly, warm, inviting office. So, the committees looked into the feasibility of erecting a bigger, better, more efficient place to practice.”

The committees settled on an architect who conceived the new office as a two-level facility—one floor above ground, the other semisubterranean. Acting on the committees’ recommendations, the architect (and, later, the construction contractor) gave Alvetro a cheerful, user-friendly building. It includes a mini-conference center where educational programs for referring dentists are held. There also is an employees-only health club that brings in personal trainers and massage therapists. Another choice feature is an enclosed garden patio, replete with barbecue grill. Elsewhere in the building is a private lounge to which employees can retreat for a bit of space between themselves and the rigors of the workday.

The upper floor is devoted to clinical services. It boasts a seven-chair, open-bay operatory and, nearby, a pair of new-patient intake chairs plus one more chair for records work. Every chair in the clinic is outfitted with the latest in digital systems. Meanwhile, bright yellow and orange hues punctuated by vibrant purple and blue throughout the interior signal that this is a happy place to be (a message reinforced by the presence of a spiffy arcade game room and by aquatic-themed wall murals).

Placing design and construction of the new office under the auspices of committees made the project far less unnerving than might have been the case had just Alvetro and one or two others on her staff tried to shoulder all the responsibilities. “We divided the burden, so no one was stressed out at any point along the way,” she says. “It turned out to be a pleasurable experience for all.”

Moreover, because employees were so intimately involved, they came away from the project feeling a stronger connection to the practice. “It’s never been a ‘this is my practice and you work for me’ situation,” she says. “Rather, it’s always been, ‘this is our practice; we’re in this together as a team.'”

|

|

||

|

|||

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products. For more information, contact

AN OPEN OPERATION

Much of what Lisa Alvetro, DDS, DMD, knows about business precepts is informed by common sense, while the rest of it has been gained from exposure to the ideas and advice of experts.

Every 12 to 18 months, Alvetro brings in a new consultant to assess the operation of her Sidney, Ohio, practice and make recommendations for improvements. Not all of these consultants specialize in orthodontic practice management. Some have expertise in the service industry or the small business arena. “I like to hear from these non-orthodontic consultants in order to gain a different perspective and be exposed to some outside-the-box thinking with regard to goal-setting, establishing time lines, measuring results, and all the rest,” Alvetro says. “Orthodontic practice consultants are great, but their perspective is by and large confined to what other orthodontists and dentists are doing.”

One of the most valuable practice-management ideas Alvetro has come across calls for openly sharing with staff delicate information about business performance. “Often, orthodontists are reluctant to reveal financial data to their employees out of fear that someone on the team will cause harm to the practice if this or that detail is known,” she says. “That’s unfortunate, because the opposite is usually what happens. The staff is typically much more loyal and invested in the success of the practice in those offices where the orthodontist embraces transparency.

“For example, if you reveal to the staff how much money the practice makes and spends, they no longer assume that every dollar that comes in is pure profit. When I began sharing my financial numbers with my team, they were floored because they had no idea that such a large sum was going out on expenditures and that so relatively little was left over after all the bills were paid.”

While Alvetro has chosen not to reveal the individual salaries of her team members to the group, they do know what is spent on salaries in the aggregate. Making the team aware of business performance information like this has given them a better perspective on how operations run. “Their eyes were opened, and it gave them an entirely new sense of mission,” she says. “They became more cost-conscious and performance-driven, since they could now see how and why their livelihood is dependent on those things.”

—RS