by Alan Ruskin

Four architects and an orthodontist weigh in on what to do when your practice outgrows your space

In deciding whether to upgrade your present facility or move to a new location, such factors as the attractiveness of the location, the amount of office space available, the base of referring dentists in the area, the population demographics and growth, projected downtime, and, of course, the cost of the project all come into play. To help those who are thinking of moving make a truly informed decision, Orthodontic Products talked to four professional office designers and one orthodontist who did it himself.

Joyce Matlack: “Where are you going to be 5 or 10 years from now?”

Joyce Matlack had been a dental hygienist and wife of an orthodontist, so she was well prepared to launch Matlack/Van Every Design, Santa Cruz, Calif, in 1985. Since then, she has been responsible for the layout of more than 450 orthodontic and dental offices worldwide.

Matlack has a degree in interior design from San Jose State, but it was her background in orthodontics that enabled her to formulate some clear-sighted views about orthodontic offices. “I saw that there were deficiencies in flow and function. Patient management is crucial and must be carried on in an orderly fashion.”

Because orthodontists see 60 to 120 patients per day, the layout—including placement of seating, equipment, and cabinetry—is crucial to facilitate the flow of both patients and staff. “The flow should be well orchestrated so patients and staff are not bumping into each other,” Matlack points out. Plus, there are the requirements dictated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Americans with Disabilities Act, making it mandatory to provide sufficient space and convenience to accommodate any person. Regulations regarding turning radius, width of corridors, and correct door hardware, to name a few, must be observed. “With so many patients, you have to be really vigilant to be legal with all the compliances,” Matlack says.

When starting an office design project, Matlack’s approach is to “treat seeing the doctor just the way the doctor would see a new patient.” Today, more than ever, she says, “Orthodontists want their office to reflect a high level of patient care, both functionally and aesthetically. More doctors are stepping up to the plate to have an office that they and their staff are proud of, and that can also contribute to the marketing of their practice.”

Matlack says her biggest challenge is trying to balance functionality with cost and the doctor’s vision. So if an orthodontist is contemplating renovation or relocation, the first question she would ask is, “Where are you going to be 5 or 10 years from now?” The key is building in flexibility for the future, so Matlack first inquires about the doctor’s long-term goals. “Do they just want to put a Band-Aid on the situation, or will the end justify the means?”

“There used to be more renovation,” Matlack says, “but as time has gone by, the costs of remodeling have grown to the point where it’s often more cost-efficient to relocate.” Labor and materials such as concrete, copper, and petroleum-based products have all risen in cost. But the main factor is that remodeling often takes more time than designing a new office because of all the variables and unknowns involved. “You have to get into the walls, and there’s a lot of phasing and scheduling that can be quite time-consuming,” Matlack says.

In preliminary discussions with the orthodontist, Matlack goes through all the pros and cons. Is the office in a viable location with good visibility? Are there good prospects for patient growth? “It’s a case-by-case thing,” Matlack says. “I help the doctor evaluate all the factors. Sometimes they have a blind spot and can’t see everything as clearly as they need to. If appropriate, I’ll bring in another professional for help with demographic studies to locate and evaluate property. Visibility is really important.”

In a recent case, the orthodontist owned office space in an excellent location, and as he approached retirement he wanted to stay and remodel in anticipation of his daughter’s entry into the profession. The 2,400-square-foot office had an “unusual L-shaped configuration,” as Matlack describes. The doctor wanted to update it and turn it into a “boutique” office, where the goal of the design was not to serve a quantity of patients, but to create a more interactive and enjoyable atmosphere.

“It took 8 months to get all the necessary permits, documents, select the finishes, furnishings and so on. We design every office so that they can easily go digital and paperless. Today, everything we see in the media has people expecting to see the latest technology, so there are computers throughout the office. When kids and their parents come into the office, that’s what they like to see,” Matlack explains.

The actual work took 5 weeks, with as many as 10 tradesmen working at one time. “It was challenging to reconfigure the space within the L-shape to achieve optimal patient and staff flow. We moved the lab to the smaller part of the ‘L’ and put the back office staff more up front. In keeping with the boutique feel, we put in a coffee bar, created group-seating vignettes, and put in decorative glass that let natural light into the reception area. Everything was state-of-the-art. The atmosphere of the office was completely transformed.”

Susanne Slizynski: “The purpose of any renovation is to solve existing problems.”

A designer who agrees with the notion that renovating can be more expensive than relocating is Susanne Slizynski, founder of Green Curve Studio, Beaverton, Ore. “Many doctors,” she says, “mistakenly estimate the construction costs for remodeling an existing facility will be cheaper than moving to a new space. However, these types of projects are usually more expensive because the general contractor has to do the project in phases, work around the doctor’s schedule, do demolition, and constantly provide protection to adjacent spaces. Also, much of the construction work will be done over long days and weekends at premium labor rates.” Nonetheless, Slizynski believes, “If you own the building or feel that the location is ideal for your practice, it will be worth the extra investment.”

The orthodontist’s staff is often the barometer of satisfaction with the office layout. “The purpose of any renovation,” Slizynski says, “is to solve existing problems that are leading to staff complaints about inefficiency, patient and staff flow, and appearance of the practice.” If the office isn’t conveying an image of excellence, staff and patient morale will be affected.

Slizynski breaks down renovation into three basic categories:

- Aesthetic upgrade: In this instance, the doctor is either satisfied with the floor plan, or else space limitations prohibit moving walls. The doctor just wants new finishes, furniture, artwork, and accessories, and any added architectural features would not require tear-out or framing. Slizynski refers to this type of project as “drama without the trauma,” and believes that such a renovation “does not require an industry design specialist to be successful.”

- Renovation without expansion: This type of project works within the existing space and includes a partial floor plan revision. A design specialist should always be consulted for any changes that affect the flow of patients and staff.

- Renovation and expansion into adjacent space or building addition: Consultation with a design specialist experienced in orthodontic office renovation and expansion is necessary. The doctor should have the designer provide several floor plan options: an optimal floor plan, and a couple of less intrusive plans. The floor plan will help the orthodontist determine several key factors, including spatial feasibility and optimization, potential downtime, and design and construction costs.

Code-compliance requirements can have a dramatic impact on construction costs, Slizynski says, so orthodontists should be sure to have the design team check with the local regulatory agency, particularly if the renovation is to include the moving of walls. If the building is an older facility, the city may require the upgrading of electrical, plumbing, and mechanical systems to current standards, and washrooms will need to be brought into compliance with ADA or American National Standards Institute code.

Warren Hamula: “Exceptional care is given here.”

Warren Hamula, DDS, MSD, founder of Modern Orthodontic Design, Monument, Colo, is a renowned figure in the field of orthodontic office design as well as a practicing orthodontist of long standing. He has designed more than 700 offices in 48 states, 50 continents, and 10 countries. Among his more recent achievements in design are the orthodontic clinic at the University of Colorado, the clinic at Columbia University, and the craniofacial department of St Vincent’s Hospital at the University of Indiana.

Hamula’s approach is logical and analytical. He looks at the typical relationship that orthodontists have with office space. “The first office,” he says, “is usually a lease and lasts 5 to 10 years, depending on space—on average, this first office is between 1,000 and 1,500 square feet—as well as quality of design and growth of practice.”

The second office is larger and might last 10 to 15 years, again depending on design, square footage, and success of the practice, as well as extra amenities. This office could be another lease or the doctor’s own building or condo purchase. “There seems to be a trend within cities toward condo purchases,” Hamula says. “This can give tax advantages, but the cost of land could be extremely high—in the area of a quarter of a million dollars. That’s why constructing one’s own building is more prevalent in rural areas, where real estate is much less expensive.”

Regarding the orthodontist’s reasons for renovating or relocating, Hamula breaks it down into two main categories: internal and external factors. The internal revolves around the desire to create an ambience that says, “Exceptional care is given here.” Central to achieving this is the need to eliminate crowding and create a feeling of spaciousness. A modern, advanced technological look is important, but warm, pleasing aesthetics and comfortable furnishings are also key elements.

External factors include the need to be near schools and referring dentists. Growth of the community and the office building’s visibility within it are major factors, as are the image of the office and ease of patient parking.

Office needs have changed as the overall profile of the profession has developed. “In the 1990s,” Hamula observes, “a busy day was 50 patients. Now it’s not uncommon to have 90 to 100 patients in a single day. Diagnosis is better, as are orthodontic materials. There is better treatment planning as well as metallurgical advancements. Instead of 15 to 20 wires, you now need only one or two. Where it used to take 3 to 4 hours to put in a set of braces, it now takes about half an hour. Appointment time is less, and there is greater time between appointments.”

These advances have dictated the need for larger and more efficient offices. On the other hand, Hamula says, “There are fewer orthodontists being trained as adequate demand is being met.” This means that competition is keen for existing clientele but is not threatened by a heavy influx of new doctors, leaving the orthodontist in the enviable position of being able to maintain mastery of his ship as long as he upgrades and expands appropriately.

Regarding the choice between renovation and relocation, Hamula believes that much depends on the size of the office. “Many times renovation is limited in what it can do for the longevity of the office, especially if the office is less than 2,000 square feet. One should not put too much money into smaller offices.”

Hamula’s modus operandi involves having the client come in for a 3-day session to finalize the schematic design. He delivers three principal drawings: a Hard-Line Schematic, a Reflected Ceiling Plan, and an AutoCAD 2000, which he refers to as the “control tower for your entire project. They are the footprint from which all other drawings and decisions are made.”

Agnes Kan: “Space simply sells.”

At CIVITAS Architects Inc, Philadelphia, partner Agnes Kan, Assoc AIA, recently helped a group of orthodontists decide whether to renovate or relocate. The doctors had been renting at the present location for the past decade. The owners of the building sold it, and the new owners offered the orthodontists a new space in the building. The doctors wanted to consider outside possibilities. Kan gave them a list of reasons on both sides of the question.

Reasons to stay and renovate:

- The location is attractive, and a similar location is hard to find.

- The existing location has a good referral basis and cannot lose it.

- The physical presence at the existing location has certain value.

- The signage has a visible landmark quality.

Reasons to move to a new building:

- The building is in a brand-new development with better parking.

- Common bathroom areas reduce the necessity and expense of building private bathrooms that must conform to code.

- A negotiable lease contract with built-in tenant fit-out cost over the duration of the lease agreement abolishes the need for a construction loan. Monthly cost is lower.

- There is a lease with an option to buy.

- Future growth can be accommodated.

- A new office offers a new practice image, new potential referrals, and limited competition.

- The practice will not suffer by relocating after construction is completed.

- New spaces are always invigorating to the staff, patients, and the doctors. This newfound energy translates to higher conversion rates.

Kan reports that the matter is still being resolved as the orthodontists have received “accommodations” from their current landlord, which may influence them to stay.

Kan emphasizes what she believes is distinctive about her firm: “We’re not just floor plan layout people. Instead, we build practices within the framework of the client’s personality, ambitions, and the character of the space to be built. We deliver uniquely creative designs to help develop a strong practice identity.”

Space is always a premier consideration. A case in point is a New Jersey orthodontist who had three “convenience-store”-type practices with very limited growth after 20 years of practice. “He found a new location in the neighborhood, consolidated all his kiosk-like practices, and his practice has transformed 360 degrees. Space simply sells.”

Projecting the desired image is another key. Kan tells of a doctor in Pennsylvania who wanted to renovate his existing office to reflect his personality and new identity. “Instantly, the patient type and volume responded to the extreme makeover of the existing practice.”

Kan is also careful to keep an eye on trends within the profession. “We study the emerging paradigms in the orthodontics industry: advancements in treatment technology, practice-management issues, marketing issues, as well as changes in society that affect our outlook on lifestyle, health, and relationships.”

Kan concludes, “Our goal is to develop elegant and exciting spaces with uncompromised efficiency, rather than flashy, loud, and surface-level trendy fashions. We’re totally hands-on with the entire process.”

S. Jay Bowman, DMD, MSD: “Where does the flow go?”

When it comes to “hands on,” S. Jay Bowman, DMD, MSD, Portage, Mich, takes it a step further to “do-it-yourself.” Bowman is one orthodontist who likes to do his own office designs. He recently put the engineering graphics course he took in college to good use in renovating one of his satellite offices in Kalamazoo, Mich.

When the Kalamazoo building was purchased by a new owner, Bowman had to give up his third-floor location but was offered a number of suites on lower floors. He chose one on the ground floor that had formerly been an oncology office. “In terms of floor plan and flow, which is so important, the office wasn’t at all like an orthodontics office should be. First of all, the building was an angular, late-’60s design with a lot of pockets that stick out. The floor plan wasn’t symmetrical, so flow was a real problem. When you entered, to the right was a hallway going to the exam rooms, with the clinical area on the left. The waiting room was actually behind those, which is not at all the way you would normally set it up.”

“At first, I didn’t know how I was going to change that, but after working on the drawings for a while I hit on a way to do it; it involved moving some walls and opening up a closet to turn it into a passageway. Since it involved moving walls around, I had to get approval from the landlord, but that was no problem since they appreciated that they didn’t have to hire an outside designer since I did that part myself.”

Bowman has a recommendation for orthodontists, even if they don’t do their own designs. “When they’re talking to designers, they shouldn’t go with just what they’re telling them, but should take some time and really look at the drawings and think about how the patients are going to move from one site to another within that office. How are people going to move past each other? Where does the flow go? Is there a way for the doctor and staff to enter and exit the office easily without being seen by the patients? There are a lot of things the doctor needs to look at while thinking about what’s going to happen from hour to hour within the office day.”

Bowman takes pride in the fact that his blueprint for his main office in Portage, a new, 6,500-square-foot building, has been used by three other orthodontists to design their offices. His concluding advice to those considering renovation or expansion? “They need to live within the office in their minds.”

|

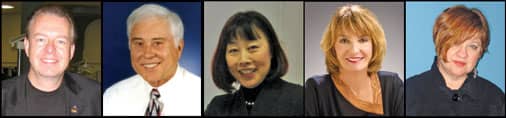

| Left to right: S. Jay Bowman, DMD, MSD, Warren Hamula, DDS, MSD, Agnes Kan, Assoc AIA, Joyce Matlack, and Susanne Slizynski. |

Alan Ruskin is a staff writer for Orthodontic Products. For more information, contact