by Justin W. Sanders

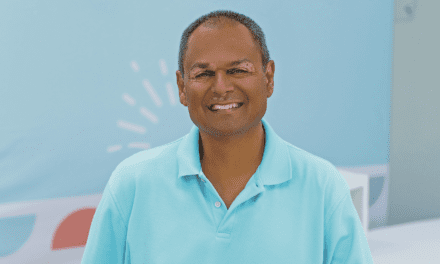

Kelly Toombs, DMD, MMSc, keeps his practice, his nonprofit work, and his race car running smoothly

Photography by Susan McSpadden

Growing up in a poverty-stricken area during the Great Depression, the philanthropist and Kansas City native Virginia Brown mostly blended in with the other underprivileged children around her. As long as she kept her lips pressed together, Brown could almost pretend she was just like everyone else. She could imagine her teeth were beautifully straight and that nobody ridiculed her whenever she slipped up and smiled.

Many of Brown’s peers and their families lacked basic goods and services, but it seemed like hardly any needed orthodontic treatment quite like she did. Her fear of smiling closed her off from the world, and her shame over her crooked teeth crushed her confidence at the most vulnerable time in her life: adolescence. Finally, late in her high school years, Brown’s family scraped together the money to treat her with braces. Her life rapidly changed for the better, but she never forgot how it felt to be scared to smile. She vowed that if she were ever in a position to help other children avoid a similar fate, she would.

Many decades later, in the mid-1990s, Virginia Brown began to set up the orthodontic charity she had always dreamed of. She had the finances to do it, and she had the will. All she needed was an orthodontist to help guide the fledgling organization. In a definitive example of the old saying, “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity,” Brown simply turned to her own family’s practitioner, Kelly Toombs, DMD, MMSc.

A graduate of the doctoral program at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry, Toombs had been operating a thriving practice since 1984. His impeccable technical skills were coupled with a reputation for immense warmth and attentiveness, especially to child patients. He was respected in his community and had strong connections in his field. Of course, Toombs knew next to nothing about setting up such a charity when Brown and her son, Tom, approached Toombs with her idea in 1997. What the Browns hoped to accomplish would be the first of its kind: A unified effort to provide braces on a large scale to those who could not otherwise afford them.

NONPROFIT PROFILE

SMILES CHANGE LIVES

Founder: Virginia L. Brown

Home Office: Kansas City, Mo

Current States with SCL Providers: 42

Specialty: Braces for children from low-income families

Founded: 1997 as the Virginia Brown Community Orthodontic Partnership

Current Orthodontic Providers: 441

Patients Per Year: Participating providers average 3

Number of children served since 1997: More than 1,500

Web Site: SmilesChangeLives.org

Toombs responded positively, and then, as he says in retrospect, “We started winging it, with no idea that it would grow into what it is today.”

A Star Charity Is Born

“I think if we’d had aspirations for a nationwide program [establishing Smiles Change Lives] would have been overwhelming,” Toombs says. “But we were looking to do something locally, which made it a more manageable task to undertake.”

To get the ball rolling, Toombs directed the Browns to his alma mater, the graduate orthodontic department at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry. There, the Browns funded the treatment of 16 children per year, an impressive total that encouraged them to take a shot at expanding the program outside the school into the local community. With the funds in place to treat an additional 30 patients per year, they returned to Toombs for further counsel. He helped them bring nine more orthodontists aboard, each of whom would treat three patients annually, pro bono. The Virginia Brown Community Orthodontic Program was born—later to become Smiles Change Lives (SCL).

Toombs’ Kansas practice includes three separate offices.

The early days of SCL were not without hurdles. Without a smooth, efficient screening process or an administrative staff in place, it was difficult to process a large and growing number of applications to determine which children were truly needy. Toombs and Tom and Virginia Brown would sometimes sit in Virginia’s apartment and sift through applications for braces themselves. Additionally, SCL’s financial structure involved compensating the orthodontists providing treatment in order to cover their costs. At first, this model “had very tangible results,” Toombs remembers. “We felt we could bring it to other cities relatively easily. That was not the case.”

For the fund-raising/compensation system to work nationally, each new branch of SCL had to be self-sustainable within its own community, using its own resources to create operational revenue. In addition to the organizational challenges involved with setting up a nationwide network of unified yet independent offices, it was, frankly, “hard to get the money together” for such an endeavor, Toombs says.

It could have all ended there, or at least never have moved beyond Kansas City. Instead, the orthodontic community at large rallied around SCL. It turned out, “A number of orthodontists in [the cities we were expanding into] didn’t care about the money,” Toombs says. “They all said, ‘You know what, that’s not why we’re doing this.’ “

Toombs makes a point of not knowing which patients come from the charity, so that everyone gets treated the same.

At the next SCL board meeting, Toombs and his fellow board members voted to stop offering compensation for orthodontists. Free from the burden of having to pay its members, the newly named Smiles Change Lives began to take off. It now had the resources to streamline its cumbersome selection process. Rather than set up a different local advisory board to screen applicants within each new state, as it had been doing, SCL brought the screening back home, continuing to use a national network of orthodontists but routing all applications through the main office in Kansas City. The growing power of the Internet helped tremendously in this transition, as SCL gradually built an informative and eye-catching Web site that also allowed participating orthodontists to screen applicants online. “It’s just functioning so smoothly now,” Toombs says.

Since 1997, SCL has grown into a national organization active in 47 states. At the time of this writing, it has provided treatment to more than 1,500 underprivileged children in need of orthodontic care. In an era when many nonprofits struggle just to survive, SCL is so successful that “people are starting to take our model and use it,” Toombs says. Recently, the Jones Foundation, a nonprofit that provides orthodontic treatment to the needy in Kansas’ Osage, Lyon, and Coffee counties, approached SCL about assistance with its own screening process. SCL accepted and now features the Jones Foundation on its Web site.

As it has expanded across the country, SCL has never lost sight of its homegrown roots. To this day, Toombs answers every e-mail from the organization’s staff personally. “I’m intimately involved,” he says. “The whole organization operates on a very personal level. Our staff is phenomenal, very talented, very dedicated individuals. I know them all personally, and if they have a question for me I want it to be a personal response. Even though we’re nationwide, this is not a huge, bureaucratic organization. And we don’t want it to be. We want SCL to operate like a small business. We’re very streamlined, very efficient, very personal.”

A Star Racer Is Born

For those who know Toombs, his role in turning SCL into a sleek, well-oiled nonprofit machine may have come as no surprise. After all, in his free time away from the workplace, he is drawn to a place where sleek, well-oiled machines are the norm: the racetrack.

“I’ve always been a car nut,” Toombs says. “From the time I was 5, I was fascinated with cars. My brother had an MGA when he was 16, and I was just in love with it.”

Toombs drove his car featuring the SCL logo at IMSA Lites at Road Atlanta in 2009. Photo courtesy of ColourTechSouth.com.

Growing up, Toombs regularly attended the Lake Afton Grand Prix, an annual car-racing event outside of Wichita that attracted specialty and exotic vehicles rarely seen in his part of the world. “I’d go watch every year and think, ‘Wow, someday I want to do this,’ ” Toombs remembers.

In addition to satisfying his craving for speed, cars gave Toombs a chance to show off the mechanical mind and manual dexterity that would eventually bring him to the field of orthodontics. The first car he ever owned was a $300 1964 MGB in need of repairs. With no prior training in auto maintenance, Toombs proceeded to rebuild the vehicle’s engine and get it running again using nothing but its repair manual for guidance.

After that defining moment, life took over, and years later Toombs found himself a happy and successful husband, father, and orthodontist—with one thing missing. He had befriended an oral surgeon who raced cars, and their interactions brought back his former yearning to try the hobby. “I realized it was the one thing I always wanted to do,” Toombs says, “and I might go my whole life without it. So I did it.”

Toombs brought his Porsche 911 to the track for a Porsche Club event. On Day 1 he received an orientation class from a seasoned instructor. On Day 2 Toombs found himself driving in time trials with that same man, and besting the stunned teacher’s fastest lap time.

Nineteen years later, Toombs still races, in cars that proudly display the SCL logo. He is a competitive, determined driver who has posted wins at club events put on by the Sports Car Club of America and professional events with the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). His vehicles of choice are the Spec Racer Ford and the Van Diemen Sports Racer, cars Toombs loves because, “In these spec classes, everyone has to have an identical car. Which does two things: It controls the cost and, because the cars are all the same, it boils down to the driver, so it makes for a very, very competitive series.

“At the racetrack, you’re all just racers,” Toombs continues. “It doesn’t matter who you are. Everyone’s part of the racing family. It’s the great equalizer.”

The Stars Align

Toombs believes that “everyone can make time to do some good in the world.”

Equality is the thread that ties together Toombs’ many pursuits. He says that his practice’s motto is, “A beautiful, functional smile provides patients with the confidence to be successful in every aspect of their lives,” because those who can’t or are afraid to smile do not have the same opportunities as those who can.

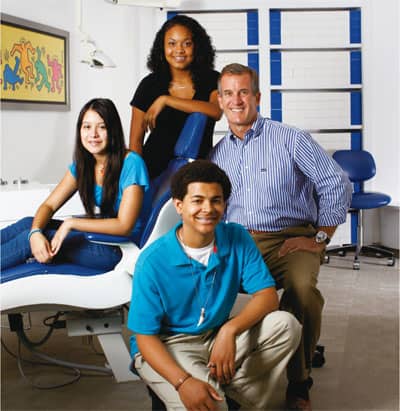

“Studies show the beauty factor is very important,” Toombs says. “People are chosen in the real world based on how they look. We see it all the time. Kids will come in who are very introverted, and they don’t look you in the eye and don’t smile, and as they go through [orthodontic treatment] they become more open and look you in the eye and smile. They get self-confidence and the presence to be in public, and are no longer teased and taunted at school. For some of these children with disfiguring smiles it would truly have become a deficit.”

In addition to serving on the national board for SCL, Toombs does pro bono work for many of the program’s beneficiaries himself. Last year, he provided braces for 20 children in need, whereas the typical SCL orthodontist treats three patients per year. To ensure that the SCL patients receive the same level of service as regular paying customers, he makes sure that “nothing in our chart comes up indicating they are from the charity,” he says. “I don’t, for the most part, even remember who are SCL patients and who are paying patients. They receive the same graciousness we hope everyone receives.”

Running a bustling orthodontic practice that spans three separate offices without sacrificing that quality of care seems daunting in itself. Toombs does it while also overseeing the nation’s largest orthodontic charity and maintaining a racing hobby that finds him competing in up to 12 events per year. An outsider looking in would chalk this up to Toombs’ gift for streamlining, for transforming what he has to work with—be it cars, his practice, or a struggling nonprofit—into a smooth, well-oiled machine. Toombs, himself, is typically humble, giving equal credit to the tremendous commitment of the Brown family, the phenomenal staff at SCL, and all of the other participating orthodontists across the country.

“The time devoted to SCL is somewhat significant,” Toombs says, “and I love my hobby, and I love to find the time for both. It is a balance, but [racing is] very therapeutic for me, and it’s important for all of us to do some good in our lives. At SCL, we do—not just in terms of teeth but in the example we set for kids. Everyone can make time to do some good in the world. It’s just a matter of setting priorities.”

Justin W. Sanders is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products. For more information, contact