By A.J. Zak

A 3D printing company that recently entered the orthodontic space is giving doctors another option for sourcing aligners at a time of increased competition from direct-to-consumer aligner companies.

Brooklyn-based Voodoo Manufacturing was founded nearly 5 years ago, and uses 3D printers to make products for a range of customers, from Gillette to Microsoft. But it wasn’t until 2018 that CEO Max Friefeld started learning more about opportunities in the orthodontic market. In the aligners space, he observed what he describes as a lack of scalable manufacturers that could compete with Invisalign and its ilk.

Voodoo sold its first aligners earlier this year. The company—which touts a standard turnaround of 5 days for the product—has about 10 orthodontic offices it works with consistently, Friefeld said. But the majority of the company’s volume comes from business clients, including direct-to-consumer aligner company Smilelove.

Voodoo customizes bags and does aligner marking for its high-volume customers, and the hope is that it will be able to support easier custom branding for clients of any size in the future, Friefeld said. In the meantime, individual doctors can have their name placed on packaging as a way to brand the aligners for patients.

“This is a product that has your name on it,” he said.

Some orthodontists have already ventured into independently producing 3D-printed aligners under their own personalized brand. Jeff Biggs, DDS, MS, who has a practice in Indianapolis, started producing aligners in-house a few years ago.

One reason was to gain more control over the process and costs as aligners have become more popular. His practice got so used to focusing on the overhead costs of brackets and wires that it didn’t pay enough attention to the costs that came with using an outside aligner company, Biggs said.

“For us, we found there was a significant increase in our overhead because we started to do more aligners,” he said. “Without doing that in-house, we couldn’t control the overhead as much as we’d like.”

Printing aligners at his practice has allowed his business to keep treatment fees lower for patients because it isn’t passing along higher costs from a third-party company, Biggs said.

Having a distinctive identity for products made in-house is key. Doctors should create their own branding instead of simply referring to their aligners as the generic version, Biggs said.

“That way, the packaging and presentation to the patient doesn’t make them concerned they’re getting a less than quality product,” he said.

Biggs’ practice is now able to offer aligners for about half of what the practice would pay a third-party company, he said.

Biggs has noticed a fast-growing interest from other doctors who are curious about producing their own aligners. Some orthodontists have even called his practice asking for information about how to get started doing it, he said.

As of early October, Voodoo’s manufacturing capacity was around 20,000 aligners per month, said Friefeld, adding that the goal is to be making 50,000 to 80,000 monthly by the end of 2019.

“There’s a huge market for people who had braces in the past but they didn’t wear their retainer or their teeth shifted a bit anyway, and they’re looking to adjust their smile with a 3- to 6-month treatment plan,” said Friefeld. “And I think that’s the sweet spot for someone entering this industry.”

More doctors are looking at the option of making aligners in-house as an alternative to Invisalign, said Friefeld, but it can be expensive and time-consuming based on how extensive a patient’s treatment plan is.

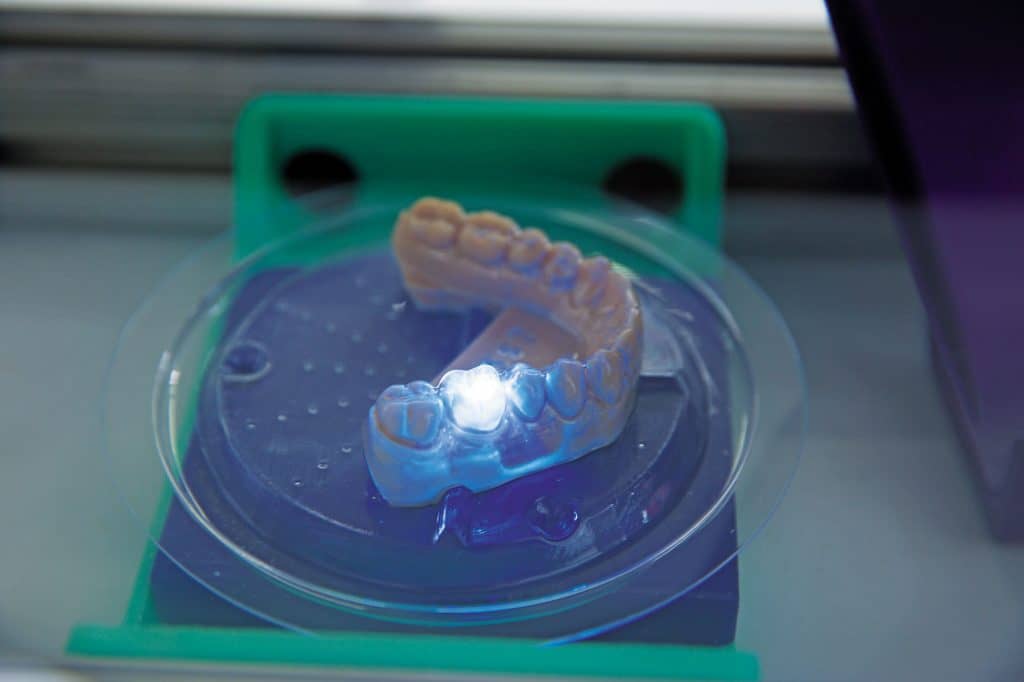

“The minute you have to make a treatment plan that might have 30 to 40 different aligners in it—each aligner, after 3D printing, you have to wash, cure, trim, sort, label—you’re looking at at least 10 minutes of labor per aligner,” he said. And that time adds up.

3D printers are faster now than they were even just a few years ago, though. When Biggs’ practice bought its first 3D printer, the machine may have taken several hours to print the models needed to make the aligners. Now, he said, some printers put out models in less than 30 minutes. Still, he can see the appeal of a doctor using a company such as Voodoo.

“I think moving forward, in-house aligners becoming more and more mainstream, having a company that can offer all the parts and pieces assembled together turnkey is a good find for an orthodontic practice,” said Biggs.

Even with growing options for aligners, though, some patients are still better served by wires and brackets. Complex cases—such as ones involving long treatment plans or moving molars—are “not just something you can pick up and do overnight,” Friefeld said.

Biggs still offers third-party aligners at his practice, too.

“We feel like there are some limitations in sort of the magnitude of the type of problem that an in-house aligner can treat,” he said, but he believes the playing field is becoming more even. OP

A.J. Zak is a freelance writer for Orthodontic Products.