by Rich Smith

Laurance Jerrold, DDS, JD, plays the roles of orthodontist, educator, and bioethicist

|

Among the thorniest business quandaries an orthodontist faces is when a patient falls behind in making payments. Does one suspend treatment until the patient brings the account current, in effect placing that person in a holding pattern? The answer is no, because doing so would be unethical and probably illegal, warns orthodontist/attorney Laurance Jerrold, DDS, JD, a nationally recognized dental risk-management educator and bioethicist.

“You cannot keep a patient in orthodontic purgatory for nonclinical reasons,” he contends. “When you recognize that the patient is not able to keep up with his financial obligations, the correct course is either to terminate the doctor-patient relationship, or continue treatment and forego the expectation of getting paid.”

Jerrold believes that most orthodontists have only vague notions about what the doctor-patient relationship actually entails. “The relationship is built around inherent rights and obligations, of which there are approximately 20,” he says. “On the doctor side, they include such things as being properly licensed and registered, making sure we supervise our staff appropriately, keeping the patient informed of treatment progress and status, not practicing outside the legally accepted scope of practice, not experimenting on patients, and so on.

PRACTICE PROFILE

|

Name: |

Jacksonville University |

|

Location: |

Jacksonville, Fla |

|

Owner: |

Jacksonville University |

|

Specialty: |

Orthodontics |

|

Years in operation: |

5 |

|

Total Clinic Population: |

@2,000 in active treatment |

|

Patients per day: |

@130 |

|

Starts per year: |

@850 |

|

Days per week: |

5 |

|

Office square footage: |

11,700 |

“Patients have fewer rights and obligations, but those they do have are critically important. They include following instructions given to them, keeping appointments, paying for services in a timely manner, giving only true statements about their health history or in response to other administrative inquiries, and conforming with accepted modes of behavior.”

Double Duty

Being an attorney as well as an orthodontist gives Jerrold a unique perspective on doctor-patient rights and responsibilities. It was in the mid-1980s that Jerrold—by then an orthodontist of nearly a decade’s standing with a practice on Long Island, NY—decided to pursue a degree in law.

“My intention was not to change careers, but to strengthen my hand in the role I found myself playing as a member of my county dental society’s professional liability claims committee,” he explains. “In New York state, every county dental society has one of these committees. Whenever a doctor is sued, the committee examines the merits of the case in order to advise the insurance carrier whether it would be best to settle or defend. I served on one of these committees, and it was an experience that really opened my eyes to issues related to risk management. I learned what dental malpractice was all about. I saw firsthand all the mistakes doctors were making.”

|

| “I’m the world’s first third-generation, board-certified orthodontist,” says Jerrold. |

Malpractice, he recalls, was a major issue for dentists and orthodontists during the early 1980s, the same as it had been for physicians a few years prior. “We were going through a malpractice crisis, and my county’s dental society decided that risk management education should be made available to the members.” Accordingly, the society tapped members of the professional liability claims committee to serve as the instructors. “After teaching risk management for about a year, I realized there were some troubling gaps in my knowledge of the subject,” Jerrold says. “I thought about what I could do to fill those gaps and came to the conclusion that the solution was for me to go to law school.”

But it was a solution achieved at enormous cost in terms of time and energy. Says Jerrold, “My typical day went like this: I’d get up at 5 in the morning, dress, then spend the next 2 hours or so on my law school homework before leaving for my orthodontic office. I’d treat patients until 5 in the afternoon and then leave my office to get to the law school campus by 6. Classes ended at 10. I’d come home, pass out, and start the whole thing going again at 5 the next morning. It went on like this for 4 years. Fortunately, I was a young man, so I had the necessary stamina.”

Jerrold earned the title juris doctor from Touro Law School in 1988. However, he had no intention of becoming the next Perry Mason. “Trial law was not something I could do and at the same time maintain an orthodontic practice,” he says. “So, the only law I practiced concerned contract matters, such as buy-sell and associateship agreements, and occasionally defending doctors at Board of Dentistry administrative hearings.”

|

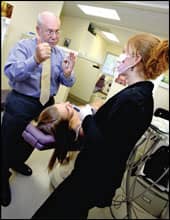

| Jerrold teaches a student and a patient at the same time. |

He also soon found himself in demand as an educator regarding the legal principles affecting everyday orthodontic practice management and risk management. His lectures on those topics were well received. Those presentations led to an invitation to write a column for the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. (His official title today with that journal is editor for litigation, legislation, and ethics.)

“As a dentist and an attorney, I was tapped by New York University to start teaching an ethics course,” he says. “Once again, after a year or so, I realized I didn’t have the necessary background or insight to do the job properly. So, in 1997, I added to my credentials by obtaining a certificate in bioethics and the humanities from a joint program sponsored by Columbia University and Montefiore Medical Center.”

Family Ties

With regard to orthodontics, Jerrold jests that he did not choose it as a career so much as it chose him: his father was an orthodontist, as was his father before him.

“I’m the world’s first third-generation, board-certified orthodontist,” proclaims the Long Island native, who admits to initially wanting nothing to do with the profession. “I was a child of the rebellious sixties, and there was no way I was going to follow in my father’s and grandfather’s footsteps.”

To prove it, as a young adult Jerrold set out to establish himself as a programmer in the nascent cable television industry. Times being what they were (it was the middle of a recession), he could not find work in that field. Frustrated, Jerrold threw in the towel and surrendered to the entreaties of his elders by enrolling in dental school at NYU.

The Jacksonville Way

Orthodontics training at Jacksonville University takes the form of a full-time, 2-year accredited program that blends evidence-based didactic instruction with clinical experience and research opportunities.

Upon completion of the program, newly minted orthodontists have the option to continue their education for an additional two semesters and receive a master’s degree in business administration. This extra component is offered collaboratively through the university’s Davis College of Business and is intended to equip orthodontists for the kind of decision-making necessary to propel their private practices to the highest levels of success.

Orthodontics is the only dental specialty taught at Jacksonville, so the orthodontic program does not have to compete at budget time against kindred programs. Being the lone dental program also makes for a thin organizational hierarchy. Jerrold says, “I report directly to the university’s senior vice president of academic affairs, so I have ample freedom to make programmatic changes. None of the traditional hurdles you’d run up against in a typical large dental school exist to prevent us from being rapidly responsive to changing circumstances.”

Orthodontic classes get under way toward the middle of August. First-year students complete a preclinical training course in which they are introduced to a variety of treatment philosophies (with emphasis on preadjusted edgewise appliances and related techniques). Within the first month of starting the program, students don clinical attire and initiate comprehensive orthodontic treatment for at least 60 patients. This takes place under the watchful eye of supervising faculty (which at present consists of seven full-time, one half-time, and two part-time instructors) in an 11,700-square-foot clinic outfitted with 15 two-chair cubicles and a pair of four-chair open bays. “We pair a junior student with a senior student in each cubicle, which facilitates mentoring, teamwork, and introduces professional pedagogy,” Jerrold says. “A key component of the education we offer is a daily diagnostic seminar in which students are taught broad perspectives about diagnosis and treatment planning. They learn that there can be three, four, or five different ways of accomplishing the same thing, and that there are nuances giving each a certain advantage over the others in specific situations.

“We also prepare our students for the many situations likely to be encountered in practice, such as parents who obstinately insist their child be treated a certain way and no other. Extensive instruction in the ethical parameters that relate to the student as a practicing orthodontist is provided as well.”

The clinic is nearly 100% paperless (it is expected to become all-electronic within the next couple of years). The equipment armamentarium includes two digital panoramic/cephalometric units, two digital PA units, a number of soft-tissue lasers, a dedicated iCAT cone-beam CT scanner, multiple TAD implant systems, and a desktop Instron machine for physical testing and clinical research. Says Jerrold, “Any bell or whistle you can imagine, we’ve got it; and if we don’t have it, we’ll go get it.”

Students who complete the program are trained so that they can “hit the ground running in whatever type of practice setting or office environment they enter,” Jerrold assures. “Nothing they encounter clinically will throw them for a loop.”

—RS

Before advancing to orthodontic residency, Jerrold did his general dentistry practice residency at Brooklyn Jewish Hospital (which later became Interfaith Hospital). He then returned to NYU for orthodontic training, completing it in 1978. After that, he split his attentions three ways: serving at the hospital, working in his father’s office, and running his own startup within a group practice. In late 1979, he purchased an office in Massapequa, Long Island. A few months later, in early 1980, he acquired his first of many satellite practices.

Practitioner to Professor

In 1999, Jerrold traded orthodontic practice for a velvet mortarboard and lilac-hued robe ensemble by becoming a full-time academician, beginning at NYU and, most recently, at Jacksonville University in Jacksonville, Fla.

“Throughout my career, I’d always given 1 or 2 days a week to teaching, and I always seemed to derive a particular enjoyment from those days. It occurred to me that teaching was something I was meant to do,” says Jerrold, who now serves as dean and program director of postgraduate orthodontics at Jacksonville University’s School of Orthodontics.

He landed there after hearing through the grapevine that the university was planning to create an orthodontic program. “It was rumored that the program would be unlike any other in the country,” he remembers. “I was intrigued, so I contacted the school to learn more. One thing led to another, and the next thing I knew I was involved in everything from curriculum planning to the facility’s architectural design.”

Jacksonville University is a private institution of higher learning founded in 1934 (its name back then was William J. Porter University; it became Jacksonville University in 1956). A top-ranked liberal arts school, Jacksonville University is noted for having a small student-to-faculty ratio and for its competitive admission policies. Orthodontics is one of the university’s six postgraduate programs.

Dealing with Card Times

Away from the rigors of the school, Jerrold can usually be found on the links enjoying a round of golf, his favorite sport. He plays strictly for recreation. “The 4 or 5 hours I spend on the golf course are an opportunity for me to think about nothing but the game of golf. It’s also very relaxing,” Jerrold says. His best score ever: 83.

There are days when golf simply isn’t in the cards for Jerrold. What is in the cards is the game of bridge. Jerrold is so good at it that he is close to achieving the rank of life master. “I enjoy the analysis that goes into playing bridge,” he says. Before she went off to college and on to a career in early childhood education, one of Jerrold’s best bridge partners was his daughter Rhya. He thought perhaps his wife of 34 years, Barbara, might take Rhya’s place, but she is too busy designing jewelry, exhibiting photographs, and handling the school’s insurance credentialing operations. Son Zack has a management job at a fashionable New York hotel, so that leaves him out of the running as well.

Meanwhile, Jerrold is approaching retirement age, but vows to keep working long after his 65th birthday. “In 5 years I want to transition into part-time teaching,” he says. “I don’t think I ever want to fully retire. I have a lot to offer still and really enjoy sharing what I know.”

One of his goals is to see the orthodontic school at Jacksonville University fully recognized by the orthodontic community as one of the—if not the—leading clinical programs in the United States. “We have an incredible faculty of young, vibrant professionals, and over the course of the next 5 or so years, you’ll be seeing from them an abundance of significant, clinically relevant contributions to the literature,” he promises. “This will happen as we increasingly position our school as a major center for clinical testing of new products and new ideas, such as clinical outcomes assessments and paying for performance.”

But the biggest hurdle the school must surmount in its bid for preeminence is politically motivated opposition from rival institutions and local professional peers. “All we ask is that we be judged on the basis of who we are and what we’re accomplishing academically,” Jerrold pleads. “If people will look at us from that perspective, our program will no longer be orthodontic education’s best-kept secret.” Giving the school a fair assessment would, after all, be the ethical thing to do.

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products. For more information, contact OPEditor.

More Pictures of Jerrold

|

|

|

|