by Greg Thompson

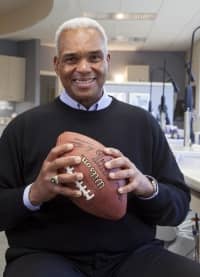

James A. Hinesly, DDS, MS, PC, gave up a pro football career to become a small-town orthodontist

James A. Hinesly, DDS, MS, PC, used to deliver teeth-rattling blocks as a left tackle for Michigan State University (MSU). Even while helping lead his team to a 1978 Big 10 Championship, though, the young Midwesterner always kept a keen eye on academic pursuits. Graduating with a biology degree from MSU fed the initial fire of medical curiosity that still burns brightly in the 53-year-old orthodontist. “I always looked at football as something I did well,” Hinesly says. “But it really wasn’t who I was.”

Thirty-two years after leaving behind the complex blocking schemes of Division I football, Hinesly now spends his time on the complexities of orthodontic treatment plans. Practicing in the rural town of Tecumseh, Mich, he has built a thriving 4,000-square-foot practice, with plans to add an additional office in the near future.

Given his history, you might expect Hinesly’s practice to be filled with gridiron memorabilia—but that is not the case. In fact, when he started practicing 22 years ago, he had virtually no evidence of his athletic background on display. Friends urged him to showcase some football dÉcor, and patients will now find a modest “wall of fame” complete with jersey, helmets, and photos. It’s a nice conversation piece, but the Howard University Dental School grad would rather talk teeth than x’s and o’s.

Hinesly’s affinity for the technical challenges of orthodontics sparked more than 400 starts last year, despite a hard-hit Michigan economy. “Don’t worry about the patients you don’t get,” he says. “Just work your tail off for the ones you do get.”

Changing the Game Plan

Part of Hinesly’s commitment entails mounting every case on articulators, a philosophy that he believes offers patients a true hands-on treatment method. “We treat every case using centric relation, or CR, as the goal,” he explains. “When you mount the case on an articulator, you are often able to see lots of vertical problems, and this dictates what you can and can’t do orthodontically.”

PRACTICE PROFILE

Practice Name: James A. Hinesly, DDS, MS, PC

Age: 53

Location: Tecumseh, Mich;

Ann Arbor, Mich (coming soon)

Specialty: General orthodontics

Years treating patients: 22

Patients per day: 75

Starts per year: 400

Days worked per week: 3 1/2

Education: Michigan State University, Howard University, and University of Michigan

Web site: hineslyorthodontics.com

Hinesly did not always treat cases this way. After several years in practice, he began to question his methods. Despite extremely satisfied patients, something was missing. After a lot of investigation, he asked a crucial question: Was it time to change a winning game plan? “I was trained at a time when we thought we could grow mandibles, and we used various functional appliances,” Hinesly explains. “After about 7 years, I had gotten frustrated with the results. Patients were happy, but I was not.”

A dinner with Ron Roth, DDS, MS, in the early 1990s profoundly changed Hinesly’s treatment philosophy and methodology. Roth (who passed away in 2005) and Robert Williams, DDS, MS, co-founded the Roth Williams International Society of Orthodontists (RWISO), a group that believes results can be improved with the inclusion of functional, as well as aesthetic, treatment goals. Along with Williams, Roth taught a 2-year course in San Francisco.

Despite an established practice and satisfactory results, Hinesly decided to take the course, and it’s a decision he has never regretted. “I thought I knew my orthodontics, and Ron was talking to me about things that I did not have a clue about,” he enthuses. “I told my wife, ‘I’m taking the course,’ and professionally it was the greatest thing I have done.” Hinesly went on to become a member of RWISO

While he acknowledges the popularity and utility of products such as Invisalign, Hinesly usually prefers other methods to achieve his goals. “I’m not a big Invisalign user,” he says. “I recently read that 60% to 70% of orthodontists had trouble finishing cases. I believe I can finish cases better, in my hands, with braces on the teeth than with Invisalign.”

For Hinesly, all new technology boils down to science, and to a lesser degree, personal preference. “When you start practicing, you may have different bracket system inventories,” he muses. “Then you reach a point in your career and decide to use one bracket system. You may decide to mount your cases and say, ‘This is who I am.’ One should always research new things to decide if they make sense scientifically. As long as the science makes sense, it can be worthwhile.”

Hinesly huddles with his team

Home-Field Advantage

After 3 1/2 chairside days per week in the office, Hinesly goes back to his desk at home, where he uses an articulator and brings in mounted models. “All of our records are digital,” Hinesly says. “I can go into the patient’s chart and review all of their records from home. We use digital film, so I can pull up their films. I usually take their tracings home, and then I can actually work the treatment plan at home, record it in the patient’s chart from home, and then it is done.”

When he’s back at the office, Hinesly relies on a solid group of chairside assistants, all of whom have 10 to 15 years of experience working with him. “If I have someone with a great personality and excellent people skills, I can teach him or her what must be done in the office,” he says. “I’ve been blessed to have a wonderful staff, so I haven’t lost anyone. We have a morning huddle every day at 7:50, and we review the day’s events. We review every patient on the schedule, anything we need, what we are delivering, or if we are repositioning a bracket. Does it take a little more time? Yes, but it contributes to a smoother day.”

Hinesly enjoys the human aspect of watching his patients’ personalities change during the course of treatment. From that first shy day in the office, the transformation begins, and patients become active partners in the process.

Right off the bat, staff members take a full set of photographs and create a montage for every new patient. Hinesly studies these images prior to the first consultation, while patients take the photos home and absorb the possibilities. “I ask him or her, ‘What do you see in this picture that you don’t like, and what things would you like to change?’ ” Hinesly says. “You have a 10-year-old or a 12-year-old in front of you, and you’ve got the parents sitting there, but I am talking directly to the children. They tell me, and use their finger to point to what they don’t like, which is invaluable.”

Listening to patients in such a direct manner was a factor in Hinesly’s decision to open a new office in Ann Arbor. Patients used to traveling more than half an hour will welcome the change, and the commute on some days will also be better for Hinesly. “I live in Ann Arbor, and my wife teaches at the University of Michigan business school [in Ann Arbor],” Hinesly says. “The second office is 5 minutes from my home, where the Tecumseh office is probably 35 to 40 minutes from home. We have lots of friends and family that will come to Tecumseh, but they have to pass two orthodontists to get to me. The additional office just makes sense.”

Hinesly started the Tecumseh office in 1994 with just 1,000 square feet, three chairs, and seven waiting room chairs. When waiting patients occasionally had to sit out on the lawn, expansion was not far behind. Additional lots directly across the street became available, and now nine treatment chairs face a glass wall that looks out on a picturesque wooded area.

All the trappings of a modern waiting room are now available, including a video space, PlayStation 2/GameCube, and streaming video that shows the before-and-after images of orthodontic patients. “That evidence speaks for itself,” Hinesly says. “And it all starts with communication. When I first meet a patient, I don’t even talk to the parents. I talk to the patient the whole time because it is going to be that child going through this process. I have to have credibility with the child, and we have to bond. From there I can get the compliance that I need down the road.”

Hinesly was the 293rd overall pick in the 1979 NFL draft, but he left the Seattle Seahawks after a year to go to dental school at Howard University.

Maximum Protection

Hinesly’s bond with young patients extends to sponsorships of the Tecumseh Youth Theatre and numerous little league and softball teams. He also helps one local student per year with college expenses. “I give a student athlete scholarship just because of my unique background, so we pick the top student athlete in Lenawee County and give him or her a scholarship every year when they are going off to college, and you wouldn’t believe the stack of applicants,” Hinesly says. “I think over the last 12 or so years, two or three have been our patients. I often say, ‘To much is given, much is expected,’ so a big part of that is giving back to the community.”

Another way he helps young athletes is by creating custom laminate mouthguards for varsity teams at local high schools. Protecting players’ safety with proper mouthguards is a passion for which Hinesly received special training from the team dentist at UCLA. He explains that boil-and-bite mouthguards are often so thin on the occlusal surface that a blow underneath the chin can cause a shock to the middle cranial fossa that contributes to concussions. Proper thickness between the teeth distributes the shock and lowers the chance for concussions.

Staff members take impressions of all the kids, and the office churns out guards that can be decorated with team colors and even jersey numbers. Hinesly’s business logo and phone number is printed on the side of each mouthguard, serving as a subtle bit of marketing and a reminder of who provided the gear at no charge.

Increasing awareness about the long-term impacts of concussions is fueling the movement toward more and better mouthguards, and America’s most prominent sports organization—the NFL—is more concerned than ever. Even so, elite players can still be spotted wearing woefully inadequate mouth protection. “Players will come to the NFL and still bring whatever concept they had in college regarding mouthguards,” Hinesly laments. “Some guys still use boil and bite, and they chew them forever because they are nervous. That is what I did when I played, and if you looked at my mouthpiece by midseason, it didn’t even look remotely like a mouthguard.”

From Athletics to Academics

Hinesly’s father played for MSU in the 1950s, including in two Rose Bowls, so football is in his blood. Hinesly’s college career included 3 years as a starter for MSU in East Lansing, Mich. In Hinesly’s senior year, the Spartans were Big 10 champions during a remarkable season that earned the offensive tackle third-team All-American honors and a spot in two college all-star games, including one in which he blocked for legendary quarterback Joe Montana.

When the Seattle Seahawks took Hinesly as the 293rd overall pick in the 1979 NFL draft, it was a mixed blessing. Despite the undeniable attraction of playing in packed stadiums, the 21-year-old graduate yearned to begin the studies that would lead him to a career as an oral surgeon—a profession he believed to be his true calling.

After all, oral surgery meant a lot of graduate education, and professional athletics would only delay this hard work.

“I never had any aspirations to play pro football—never, not a day,” says Hinesly, who stands 6 feet 2 inches tall and weighs 250 pounds, just as he did in college. “Playing football in college was fun. But what happens is you play against guys, and all of a sudden one gets drafted. You see him play on Sunday and think, ‘That guy wasn’t that good. How is he playing on Sundays?’ You get curious to see if you can play at the professional level, and that was probably the only reason I played for the Seahawks.”

After a year of pro ball, however, the itch for a medical career only grew stronger. How many uninjured athletes voluntarily give up a pro career? The group is undeniably small, but Hinesly is a proud member of that exclusive club. He ultimately turned away from athletics and channeled his dedication eastward to Howard University Dental School in Washington, DC.

Tackling Orthodontics

Hinesly had an uncle who was an oral surgeon on faculty at Howard, and he was able to live with his uncle during all 4 years of dental school. “People ask, ‘Wasn’t football the best 4 years of your life?’ and I say, ‘No, the 4 years at Howard were probably my best 4 years,’ ” Hinesly says. “It was tough, but I enjoyed every day. I eventually came back home and got my Master’s Degree in Orthodontics at the University of Michigan, and I have been practicing ever since.”

So what’s more difficult—undergrad studies with all-consuming football practices, or dental school? Without hesitation, Hinesly says dental school. “I knew that this [dentistry] was my career, and I went after it as if my life depended on it,” says Hinesly, who has also gone on to become a diplomate of the ABO. “It was similar to the approach I had playing football. I was able to take those same energies and use them for dental school and in my practice.”

When it was time to practice orthodontics, Hinesly used the attention to detail, the discipline, and the organization he learned in football. As a player, he strove for perfection, and he believed that success in orthodontics was simply a matter of transferring that same determination to a different venue in life—be it an urban or rural setting. “Many said to me when I graduated from school, ‘As a black orthodontist, you have to go to an inner city,'” says Hinesly, who also serves as a mentor for the ABO. “I worked for two orthodontists when I first got out of school—one in a large city, and one in a smaller town. The one in the smaller town got to know everybody, and everybody knew him. That fit my personality better, so I went looking for a smaller town as opposed to a big metropolitan area. That is ultimately how I chose the rural setting that I am in.”

As a former athlete, Hinesly still likes to exercise a lot, and that dedication has kept him firmly at his old playing weight. He has managed to avoid major injuries, and is usually able to work out 5 or 6 days a week, getting most of his cardiovascular conditioning on the elliptical machine. “I have a passion for golf and try to get out twice a week,” he says. “Mentally, I golf more than that.”

On Saturdays, Hinesly still follows college football. But as a graduate of both MSU and the University of Michigan, who does he root for when the two play their annual rivalry game? Hinesly says he can’t lose either way, but then adds a quick “Go Green” to show that, through years of orthodontic practice, he has maintained his allegiance to the MSU Spartans. [ All photos by Jim West ]

Greg Thompson is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products. For more information, contact