by Rich Smith

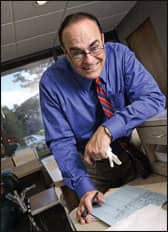

John W.M. Carter, DDS, MScD, is an orthodontist, educator, and illustrator

|

| John W.M. Carter, DDS, MScD Photos by Robin Miller |

Crack open any orthodontic textbook and leaf through its pages. Scattered across them will be illustrations and technical drawings of brackets, wires, appliances, instruments, and anatomic structures.

Traditionally, these images had been painstakingly rendered by hand: the more detailed the drawing, the more challenging it was to pen. Nowadays, these illustrations are produced by computer with a lot less effort and in a fraction of the time—except those drawn by John W.M. Carter, DDS, MScD. Carter is a private-practice orthodontist from Overland Park, Kan, who occasionally hand illustrates orthodontic textbooks published by the University of Missouri, Kansas City, where, for 18 years, he spent most afternoons and Fridays as a clinical associate professor of orthodontics.

“The hardest part about illustrating a textbook is making sure the drawings are accurate,” Carter says. “I’m allowed a certain degree of artistic license: for instance, I can draw an archwire three or four times its actual size to call attention to it. But that archwire still has to show the bend in the exact right place and be properly proportioned if the reader is to understand its correct relationship to whatever else is depicted in that same frame.”

It can take long hours to produce a single illustration, Carter admits. “The first step is to create a line drawing in pencil,” he says. “Then I place over it a sheet of clear acetate or a sheet of paper that I can see through when light from a lightbox shines through it so that I can transfer the penciling. After the transfer is completed, I refine it several times. Then, in the semifinal stage, I go over it in ink. To final it, I use draftsman tools—a T-square and a triangle—to produce the true horizontal and vertical lines that result in a tight, perfectly square illustration.”

Art and Science

PRACTICE PROFILE

|

Name: |

John W.M. Carter, DDS, MScD, PA |

|

Location:: |

Overland Park, Kan |

|

Owner: |

John W.M. Carter, DDS, MScD |

|

Specialty: |

Orthodontics |

|

Years in practice:: |

26 |

|

Patients per day: |

35 |

|

Starts per year: |

250 |

|

Days worked per week: |

4 to 4.5 |

|

Office square footage: |

2,500 |

Carter’s interest in illustration traces (no pun intended) back to his childhood in Prairie Village, Kan, on the outskirts of Kansas City. By the time he graduated from high school, his talent was undeniable. “Everyone told me I ought to pursue a career in commercial art, and I assumed that’s how I’d make a living for myself someday,” he says. “So, in college, that’s what I majored in: commercial art.”

But before entering college, Carter signed up for the Navy Reserve rather than wait for Uncle Sam to call him up in the draft. “I was 17, the war in Vietnam was at its peak,” he says. “By going into the Reserve, I was able to delay my start of active duty until after completing college. And, then, I would only have to spend 2 years in active duty rather than 4, followed by 2 more years in the Reserve.”

|

| Carter assesses his work as he ties ligature wires. |

Once that active duty tour began, the Navy, aware of his commercial art degree, put Carter to work as an illustrator draftsman at a reconnaissance-gathering facility in Washington, DC. “My unit was involved in providing to the Pentagon hard-line drawings and silhouettes of Soviet warships that we interpreted from photographs,” Carter says, adding that it was not truly hush-hush stuff (although he possessed the highest level of security clearance). “I was allowed to take home my original drawings of those and other ships at the close of my assignment with that reconnaissance unit.”

After his obligations to the Navy Reserve ended in 1976, Carter joined the Army Reserve and spent the next 21 years as an officer in that branch’s Dental Corps. He retired from the military not long ago, having attained the rank of major.

During his active-duty years, Carter realized that illustration was a natural fit with two other subjects he loved: science and biology. This awakening led him to later return to college on a part-time basis in a quest to obtain a degree in biology. “I had a full-time job in those days as a junior art director for an advertising agency in Kansas City,” he says. “That’s how I supported myself while in school.”

Scout’s Honor

Show Overland Park, Kan, orthodontist John W.M. Carter, DDS, MScD, a busy street corner with a little old lady standing at the curb, and instinctively he will rush over to help her across. That is what a near-lifetime of participation in the Boy Scouts of America can do to a person.

“I love Scouting,” Carter enthuses. “I was an Eagle Scout, and so was my son, John Ryan William, who’s now 26 years old.”

Carter can thank his twin uncles for interesting him in the Boy Scouts. “My uncles were Boy Scouts, and I remember as a child going through their bedroom at my grandparents’ house. Their room was filled with all kinds of amazing stuff they had made as part of their Boy Scouts activities: bows and arrows, camping equipment, you name it. It was like being in a wonderland.”

After high school, at the end of his Eagle Scout days, Carter continued participating in the organization, first as an assistant scoutmaster and then as a full-fledged leader of local troops. “In 1997, I was one of the three scoutmasters chosen to represent the Kansas City area at the Boy Scouts national Jamboree,” he says, beaming.

Carter and his homemaker wife, Colleen, also have a daughter, Caitlyn, 24, who was not involved in Scouting but enjoyed family travels. “As a young family, we loved taking road trips,” Carter remembers. “Our inspiration was the first National Lampoon’s Vacation movie that starred Chevy Chase. We didn’t have a lemon of a station-wagon like in the movie; our road trips were always taken in a full-size conversion van, and it never let us down. We’d load the van with all our bags and supplies and spend the next 10 days traveling the highways to great destinations, such as Yellowstone National Park and the Grand Canyon. There are few major vacation spots around the country that we haven’t visited or seen.”

—RS

His next move was to enroll in the dental school at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. “My father was a local pedodontist and dental educator whose footsteps I hoped to follow in,” Carter recalls.

While in that program, Carter was given his first shot at using his illustrating skills in a dental environment. “I was named the editor of the school’s yearbook, and did all the design work and page layouts myself,” he says.

More recently, Carter’s artistry has been put to work designing annual meeting brochures, logos, certificates, and even jewelry for the College of Diplomates of the American Board of Orthodontists. He has served in that capacity for nearly a decade now. A firm believer in the value of board certification, Carter also is a past-president of that organization.

Carter graduated from dental school in 1978, then went on to study pediatric dentistry at Boston University’s Goldman School. In 1980, he undertook orthodontic training back in Missouri at St Louis University’s Graduate School of Orthodontics, wrapping up there in 1982.

At that point, he returned to Kansas City to be close to family and friends. It was then that he decided to enter orthodontic practice with an office that he would start from scratch in Overland Park.

Hands-on Approach

From the first, Carter has been a proponent of the hands-on approach to treatment.

“I’m Old School in that regard. The teachings of Dr Charles Tweed are foundational to my thinking,” he says. “For example, my appliances are straightwire, but I also do a lot of bending. When I finish a case, I put in a lot of modification bands to get the teeth just right. Quality results are what I’m striving for, and I don’t think that’s attainable if I place responsibility for bending finishing wire and performing activations entirely on my staff. The reason is they do not have the training or board certification to see what I see when it comes to bending wire with arch coordination in mind.

“Hands-on is the only way to treat patients if you believe, as I do, that every patient is different. As such, no one size of wire is going to fit all. Treatment, therefore, has to be customized. And, if it’s customized, the only way that’s going to be possible is with a hands-on approach. Delegation of this responsibility to staff is simply not going to give the results you’re hoping for.”

|

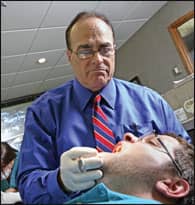

| Carter’s hands-on approach emphasizes early intervention starting around age 7. |

As for actual treatment, Carter’s philosophy emphasizes early intervention. “I’m not one to allow the mouth to get as bad as it can before starting orthodontic treatment,” he says. “Having a pediatric dentistry background and 4—not 2—years of training in growth development, I feel it’s very important to mold the face as the child is growing. Once the child reaches age 12, 13, or 14, making changes to the face is not as easy as it is when the child is still only around 6 or 7. You can guide the eruption of teeth and develop the face orthopedically from 7 to around 11, then start them in full braces.”

Carter expresses concern that some orthodontists who offer early treatment use movable appliances. “My view is that, when you’re working with a population as young as this, fixed appliance design is the better choice in about 99% of the cases, simply because it requires the least amount of cooperation from the patient to get the job done,” he says. “For example, you can spend 9 to 12 months working toward expanding an upper jaw with removable appliances or using a quad helix that you take in and out and re-energize or make anew to expand off of the teeth alone. But the more effective route, in my opinion, is to cement onto bands a modified Haas appliance that expands by putting pressure on the palate. Within 6 weeks it will have the palate open; 3 months after that it will have the bone filled back in, and about all I’ll have to do during that time is check to make sure there are no loose bands.”

|

| After 18 years of simultaneously teaching and practicing, Carter has slowed his pace a bit. |

|

|

Multitasking in the Present, Planning for the Future

The Overland Park office Carter occupies is the same one he has leased for the past 20 years. In 2002, he remodeled the place, top to bottom, to increase the square footage (which now stands at 2,500) and freshen appearances as well as to dramatically improve workflow by means of a more efficiency-minded floor plan.

“My main operatory has four chairs that run in a straight line along a bar containing hi-lo pullout drawers for rear delivery of instruments and materials,” he says. “I prefer rear delivery, and I prefer it for a couple of reasons. One, need items can be accessed without my having to step this way or that. Two, instruments are always behind the patient, which isimportant when dealing with a very young population. The last thing I want to happen is for a young patient to be able to reach in front and grab hold of a sharp instrument.”

|

In Carter’s configuration, what is in front of the chair is a television monitor that plays cartoon shows, movies, and other videos that youngsters can choose to occupy themselves while Carter is working on their teeth.

“I also have a secondary operatory in a separate room. It has two chairs and is used mainly for radiology and records,” Carter adds.

At about the same time he launched his practice, Carter won a graduate teaching appointment at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, School of Dentistry. “I wanted a part-time teaching position, but it ended up being a minimum full-time teaching career: afternoons Monday through Thursday and all day Friday,” he says, clarifying that this left him the mornings during the first 4 days of the workweek and all day Saturday to see his private-practice patients. “I kept this schedule for 18 years until I began wanting a less demanding pace. Now it’s down to just Fridays, which I spend doing consulting work at the Cleft Palate Clinic operated by the University of Kansas’ Department of Plastic Surgery.”

Now there is talk of one day expanding the Overland Park practice to make room for Carter’s son, John Ryan William, a Baylor University graduate who is considering leaving his job with a major accounting firm in Dallas and returning to school for dental training. He was a pre-dental student at Baylor and has a degree in forensic science. “My son … is extremely personable and great with people, which is one of the reasons I think he’d be perfect as an orthodontist,” Carter says. “And, if that’s what he ends up deciding to do, I’d like to be able to one day turn my practice over to him.”

Carter’s son has not exhibited the same artistic gifts that make Carter a first-rate illustrator. But, even so, it can be said without wincing that the younger Carter—like Carter himself—is clearly drawn to orthodontics.

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Orthodontic Products. For more information, please contact