by SUSIE VANDERLIP

Understanding the physical changes your patients are going through can help you communicate better with them

It has been my privilege to reach 25,000 individual struggling teens through such conversations. And from these conversations, I have learned an important lesson: how to talk to teens so that they can take positive action on their own behalf. In the world of orthodontics, no doubt you have had days when you have wished that you had that magic wand to zap a teenage patient into communication, compliance, or just a pleasant attitude!

Tips for Talking to Teens

So, what more can you do to motivate a teenage patient to cooperate with his or her orthodontic program?

Remember that teens often have low self-esteem that interferes with their ability to believe that they are worthy of self-care or that they are likable, no matter what you do with their teeth. Authoritarian judgments, nagging, and punishments often backfire with such teens. Connecting with them about their feelings, accepting them as they are, and compassionately encouraging them can go a long way toward gaining compliance.

It helps to understand teenage brain development and its impact on how they think. Teenagers have an undeveloped prefrontal cortex. Teenagers’ prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that helps them reason and grasp consequences, starts growing at age 11 or 12 and keeps growing until they are 24 years old. This means that at 13 or 15, or even 17, you (and certainly their parents) may wonder, “What in the world were they thinking?” when a teen loses an appliance, completely neglects to brush his or her teeth, or does some other such frustrating thing. The truth is that they truly aren’t thinking some of the time. Their brains aren’t yet wired to grasp and be motivated by the long-term consequences that adults can envision.

This implies that it is counterproductive to dominate, nag, scold, or complain about this “unacceptable” behavior—because it is, in a sense, normal. Scolding only diminishes teens’ self-esteem further and encourages them to act out their self-loathing, fear, anger, and hurt through recalcitrance and depression, leading to self-neglect, withdrawal, and a plethora of available, dangerous escapes. Instead, consider using “affirming communication techniques.”

Affirming Communication Techniques

These methods for communicating with teenagers are useful for orthodontists and parents alike.

Be aware of your body language.

? Look them in the eye.

? Keep a calm, nonjudgmental attitude.

? Have a calm, relaxed expression with a mild smile on your face.

? Relax your arms by your sides rather than having them crossed on your chest with your head thrust forward in a threatening position.

Share stories, and show interest in their world. Teens respond to adults who share stories with life lessons rather than preach at them. Consider sharing a story about what it was like for you as a teen or for your teenage friends when you were their age (whether the story is real or made up). For example, share about a friend from when you were in high school who had very unattractive, crooked teeth and clearly felt unlikable because of his looks. As a result, the teenage friend started hanging with a group of kids who didn’t feel they “fit in” with the popular crowd. Some teens in the group were experimenting with drugs, and eventually he tried using drugs, too. He stopped caring about school and never went on to college, even though he was smart enough. He never lived up to his potential or made his dreams come true, which might not have happened had the friend done something positive for himself like straightening his teeth to feel more hopeful about his life.

Emphasize the feelings the teens had in your stories and your own feelings about it. Teens relate to feelings. Nearly every teen has felt self-loathing on multiple occasions. Every teen has felt unloved by his or her parents and peers at one moment or another. Every teen has the fear of not being accepted and loved, of failing to meet parent’s expectations.

Consider getting technologically savvy. Do you have an iPod? Why not talk to teens about it: what music they’ve downloaded, which music groups they prefer. Consider having a staff member go online to iTunes and print out the top songs of the week. This list could make a good conversation starter to help build rapport with teens. Teens use music extensively to connect with their peers. Why not with the orthodontist’s staff as well?

Ask for their opinions. Conclude stories by asking teens for their opinions: “Do you know someone who feels really bad about themselves, too? What would you tell them to do?”

Give them safe passage to talk. Allow them to have an opinion, even if it seems “wrong,” “immature,” or “scary” to you. And when they talk, listen listen listen! Try responding with, “I feel uncomfortable with your feedback. You said you think that the teen I shared about did the right thing hanging with a bad crowd because she didn’t like herself. A lot of bad things happened to her because of that choice. Maybe if she had talked to her parents, they could have helped. What do you think her parents could have done to help? Are you comfortable talking to your parents about how you are feeling?”

If a teen shrugs or says no, offer to talk to his parents with him and broach a subject that he seems fearful of handling by himself.

Play fair, and praise often. Acknowledge what teens are doing right, rather than immediately noticing the things that they are doing wrong. Help them feel good about small gains, then suggest necessary improvements they can make.

Don’t take a teen’s failure to comply or an “attitude” personally or as your own failure. In this way, you can stay more patient and be a better listener and encourager.

Release unrealistic expectations while maintaining appropriate expectations and making sure that there are consequences for failing to meet commitments in their orthodontic care. Have clear procedures and expectations, then discuss with your teenage patients the consequences in advance so that there are no surprises. Consider asking teens to define the consequences/rewards they think would be the most motivating for them. Then, have a conversation with the parent and the teen together; perhaps even sign a contract between them. Consider having parents agree to consequences should they be too dominating, nagging, or scolding.

Bartering tools for teens are very basic, and the most powerful of all are those that disconnect them temporarily from their peers. Suspending cell phone or Internet use, or access to a favorite pair of “popular” jeans or tennis shoes, makes for powerful consequences when necessary.

It’s Not a Popularity Contest

Key to all communication with a teen is to accept that teenagers will not always like you. Guiding a teen is not a popularity contest, to be sure. If you continue to show them that you care by being compassionate, patient, kind, courteous, and sincere, teenagers will listen. Though you may not always get a verbal agreement, and will sometimes get barely a head nod, they are listening and care most about being accepted and loved—perhaps even by their orthodontist and staff.

In conclusion, orthodontists and their staff play a vital role in a teenager’s self-esteem. Providing a teen with a pleasant appearance is a worthy and wonderful goal in and of itself. Adding an attitude of acceptance, kindness, and patience; a listening ear; and a personal story gives them a safe place in their world to be themselves and an anchor of wise guidance to help them make good choices.

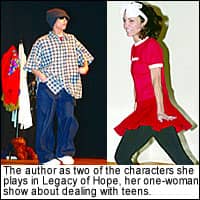

Susie Vanderlip is an expert in teen issues; the author of 52 Ways to Protect Your Teen: Guiding Teens to Good Choices and Success; and a nationally renowned professional speaker in middle schools, high schools, and youth and adult conferences across the United States and Canada. Her original one-woman theatrical school assembly and conference keynote, Legacy of Hope, incorporates dance, drama, and powerful personal stories that give hope to youths and enrich emotional intelligence in both youths and adults. She can be reached at (800) 707-1977 or [email protected].