by Anita D’Alessandro

OP: How long has 3D CT been used for orthodontics?

Palomo: The first cone beam CT [CBCT] machine in the United States was installed in Loma Linda University [Loma Linda, Calif] in 2000. Just 6 years later, hundreds of CBCT machines are already installed and in use. This rapid growth in presence of such a different technology is unusual, and reinforces the idea that CBCT is here to stay.

OP: What do you see as the advantages of using 3D imaging as opposed to plaster models?

Palomo: Plaster models were probably the last orthodontic records to make it to a digital format. One of the possible reasons was that it was the only 3D record we had of our patient. The adoption of the plaster models in their digital format was not as rapid as other records, and this could be because besides the advantages that a digital format would bring, there is little additional diagnostic information gained. With CBCT we can see the dentition in 3D with the addition of the teeth roots, which cannot be seen in either plaster casts or electronic casts. This additional information could be reason enough for a change. Another advantage is that if we can use the dentition seen in a CBCT as a replacement for dental casts or electronic casts, we would not need to take impressions and/or pour the impressions, and the information would be collected at the same time as the radiographs, combining the taking of all those records to sometimes less than 10 seconds.

OP: Are there clinical disadvantages to using 3D CT?

Palomo: There is a learning curve inherent to every new technique and technology. In the beginning, the clinician will probably spend more doctor time on the diagnosis than she/he was spending before. But we are confident that the analysis is simple and comprehensive enough, and that the clinician will be able to easily adopt it in the clinical or research environment.

OP: Among your peers, roughly what percentage use 3D CT clinically?

OP: What do you see as the barrier(s) to orthodontists’ using 3D CT?

Palomo: At this point, probably the cost of this technology is the major obstacle. The complete cost includes not only the actual machine, installation, and room remodeling, but also staff cost. In my opinion, to function in an effective way, the clinical setting will need a designated staff member to run this machine. This person would need additional training not only to take the images, but also prepare them, so doctor time is not used instead.

OP: What inspired you to develop your standard for analyzing 3D images?

OP: What are the parameters you measure?

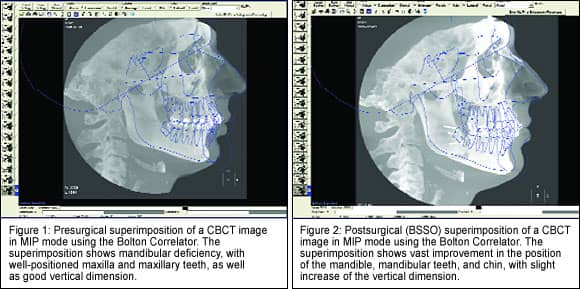

Palomo: There are no fixed parameters. The clinician is in control, and the superimposition is best done in a custom way according to the patient’s needs. Suggested superimpositions are on individual arches, to establish the position of the dentition; superimposition on the cranial base; and superimposition on the upper soft-tissue profile, to determine the way to best improve facial aesthetics.

OP: Does this require additional software?

Palomo: Both the Bolton Correlator and the 3D Bolton Standards are stand-alone programs, which means that once their installation is complete, you do not need anything else to be installed.

OP: Have you applied the standards clinically yourself?

Palomo: We have superimposed 3D images and used CBCT data, but we think that additional tests are still needed before we release it for use in the clinical environment.

OP: Have you published anything specifically on this topic?

Palomo: Our team has presented on this topic on the AAO meeting, among others.1,2

OP: How long before these standards are available for use?

Palomo: We expect to have them available for clinical use within 6 months.

OP: What else should practicing orthodontists know about your standards?

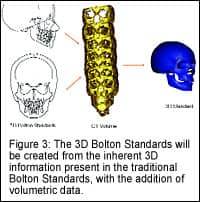

Palomo: The 3D imaging of our patient, who is a 3D entity, was just a question of the technology catching up to our needs. At this point, CBCT machines are able to provide us with an accurate 3D representation of our patients, and it is unlikely that we would go backward to a 2D imaging of our 3D patient. We may have different technologies in the future that may replace CBCT technology, but it will have to be in 3D. The best way to analyze a 3D image is definitely a 3D analysis or comparison. The 3D Bolton Standards would fulfill that need in a simple and user-friendly interface.

J. Martin Palomo DDS, MSD, joined the Case Western Reserve Department of Orthodontics in 1998, and his research focus is on informatics and 3D imaging. He has presented more than 30 lectures in the United States, Canada, South America, and Asia, and he has authored several publications, on craniofacial imaging. He is currently the director of the Craniofacial Imaging Center at Case School of Dental Medicine and also maintains an intramural private practice in Cleveland. He can be reached at [email protected].

References

1. Palomo JM, Subramanyan K, Hans MG. The creation of 3D standards for CT images. Digital radiography and three-dimensional imaging. Craniofacial Growth Series. Vol 43. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for Human Growth and Development, The University of Michigan. 2006:231–246.

2. Palomo JM, Subramanyan K, Broadbent BH, Hans MG. The 2D and 3D Bolton standards. KieferorthopÄdie Nachrichten (Orthodontic News). Oemus Media AG. 2006;7/8:4–5. (German)