by Christopher Piehler

An orthodontist and his brother are on the fast track to decreasing treatment times

OP: What is your orthodontic background?

Wilcko: I received my DMD from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine in 1980 and my Masters in Orthodontics from West Virginia University [Morgantown] in 1982. During this period, on my own time, I developed a calcium hydroxide-based root-canal sealer that is still on the market today. In 1982, I opened my private orthodontic practice in Erie, Pa, which I still operate as a full-time practice. In 1995, my brother M. Thomas Wilcko, DMD (a periodontist and Harvard graduate in 1975), and I developed our process of moving teeth very quickly. My brother and I are both consultants to Bethesda Naval Hospital [Bethesda, Md].

OP: What made you want to invent a system to speed up orthodontic treatment?

Wilcko: The bottom line is that the shortened treatment times brought a new population of orthodontic patients into my practice that would not have otherwise had orthodontic treatment due to the length of treatment. Time is increasingly becoming a more valuable commodity. We are living in an era when people prefer receiving things more quickly than in previous times.

In my practice, high-school students and adults tend to have a lower acceptance rate. Teenagers do not want to spend a majority of their high school experience in braces, and adults have a negative view of years in treatment. In many cases, offering a shorter treatment can be the deciding factor in patient acceptance. Teenagers often want to have the option to schedule orthodontic treatment around events such as athletic seasons, drama productions, and graduations. It is not uncommon for adults to want orthodontic treatment completed in preparation for weddings, career moves, and prosthetic work. Without this shortened treatment option, many patients would decline treatment.

OP: Who came up with this system? Was it a collaboration? How much research did you do on the system before presenting it to the orthodontic community?

Wilcko: Since my original basic science research in bone turnover more than 20 years ago, I truly believed that it would be feasible to physiologically speed up tooth movement. A long-term literature review revealed previous procedures used to reduce treatment time. Although references date back to the late 1800s, Heinrich KÖle is generally credited with introducing the first modern procedure combing decortication and subapical osteotomies. He was the first to describe the physiologic mechanism responsible as “bony block movement.” This concept of bony block movement prevailed for more than 40 years.

Our background literature review began in 1994, with the protocol for the first patient treatments and research having been developed at the beginning of 1995. The research records at this point were composed of conventional records, and surface CT scans pretreatment, post-treatment, and after 2 years of retention.

OP: What are the basics of this procedure?

The orthodontic treatment involves relatively routine mechanics. However, the rationale and order of procedures can be different from conventional treatment. A working knowledge of the physiological basis of our procedure is needed to understand these concepts and achieve the speed and high quality of results possible with our procedure.

OP: How does the system work on the cortical bone to allow the teeth to move faster?

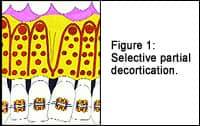

Wilcko: The periodontal surgery sets up a cascade of physiological reactions that result in the partial demineralization of the bone surrounding and supporting the teeth. This process is RAP. This allows the teeth to move three to four times faster than they do in conventional orthodontic treatment. The bone remineralizes as treatment reaches its final phases and the patient goes into retention. This pervasive demineralization of the alveolar process does not produce excessive mobility of the teeth but is sufficient to produce very fast tooth movements.

OP: What is the average time it takes you to treat a case using this method?

Wilcko: Most mild to moderate decrowding cases can be completed in approximately 3–6 months, with moderate-to-severe decrowding cases completed in 6–8 months. Extraction/space-closing cases can take 4–8 weeks longer to complete.

So much attention has been directed toward the dramatic reduction in treatment times that very often the equally important aspect of increased degree of tooth movement is overlooked. We can extrude, intrude, and protract teeth much further than would be possible with traditional orthodontic treatment alone. We have also perfected a very efficient space-closing technique that makes it possible for us to accomplish extraction-space closing in 4–8 weeks with orthopedic forces or with very light but extremely efficient orthodontic forces. We can decrease the need for extractions, but skeletal considerations will still make it necessary, in certain situations, to extract teeth. Because of the increased degree of tooth movement, orthognathic surgery occasionally can be avoided. In other situations, our method can be used in conjunction with orthognathic surgery to dramatically shorten the overall treatment time.

Increased age certainly becomes much less of a deterrent to orthodontic treatment. The increased bone turnover makes it possible to treat a healthy 75-year-old patient as readily as a 15-year-old patient. In many respects, this is the orthodontic equivalent of the “fountain of youth.” The mean treatment time for decrowding is 6.1 months.2

OP: What types of malocclusions can be treated with your system?

Wilcko: Most dental malocclusions can be treated with our system. Exceptions may include certain severe skeletal classifications.

Wilcko: No. Full treatments are usually only needed when the patient desires a very fast correction or when conventional treatment cannot obtain the same result. Limited treatments can be done to accomplish limited corrections or when the length of treatment is not as much of a concern. For example, surgical exposures can be done with our techniques to help in drawing impacted teeth into position while treating the rest of the mouth conventionally.

OP: What has been the reaction to your system from other orthodontists?

Wilcko: At first, there was a lot of skepticism because the claims seemed so extraordinary. There are still many misconceptions about our procedure, but those misconceptions are fading. As people attended our lectures and information has been disseminated, many doctors have realized that this is a routine type of treatment that can be in-corporated into any orthodontic practice. During our lectures, we often hear that the information makes perfect sense.

For the greater part of the past 10 years, we have been working closely with Donald J. Ferguson, DMD, MSD, professor and chair of orthodontics at the Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine, and director of the Advanced Orthodontic Training Program. Under Dr Ferguson’s supervision, our database has been studied extensively in formal research projects to verify shortened treatment times,1 reduced root resorption,2 increased alveolar base,3 and increased stability.4 This has resulted in numerous journal publications,5,6 journal abstracts, and university research theses.

OP: What are other clinical implications of your method?

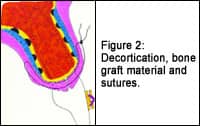

Wilcko: There is more alveolar bone support for the teeth and soft tissue following treatment as a consequence of utilizing the bone-grafting procedure. Teeth can be moved much further than in conventional treatment due to this additional periodontal support. This “in vivo tissue engineering” procedure can also be used to reduce lip curls/creases and, to a certain degree, correct weak profiles. Therefore, fewer permanent extractions are needed to resolve moderate to severe crowding. Also, in certain situations, orthognathic surgery can be avoided in lieu of this much simpler and less aggressive in-office surgical procedure. An example of a difficult treatment to reopen bicuspid spaces to correct a Class III malocclusion without orthognathic surgery and in preparation for prosthetic replacements is shown in Figures 3A–3D.

Wilcko: We offer a 2-day training program. Many case examples are presented, along with the proper mechanics needed to accomplish the tooth movements. Dr Ferguson typically presents the physiological basis and rationale of our process. Our course teaches the essentials for being able to successfully treat a great variety of situations. With this approach, we have been able to dramatically reduce the learning curve for this technique. Reading this or any other article cannot take the place of an intensive 2-day training program.

OP: Do you have plans for other ways of making orthodontic treatment more efficient?

Wilcko: This is truly just the dawn of tissue-engineered rapid orthodontic treatment. In many respects, this treatment could be compared to implants in the early 1990s. We knew that implants worked, but their full potential had certainly not been realized. We have learned how to create bone where there was insufficient bony support for the teeth, and we have learned how to incorporate our procedure into most orthodontic treatment plans. As concerns tissue-engineered rapid orthodontic treatment, the best is surely yet to be realized, and yes, we do have ideas of how to improve this technique. It is certainly a privilege to be a part of this treatment modality as it continues to evolve.

William M. Wilcko, DMD, MS, can be reached at [email protected].

References

1. Frost, HM. The regional acceleratory phenomena: a review. Henry Ford Hospital Med J. 1983;31:3–9.

2. Hajji SS, Ferguson DJ, Miley DD, Wilcko WM, Wilcko MT. The influence of accelerated osteogenic response on mandibular decrowding [abstract]. J Dent Res. 2001;80:180.

3. Machado IM, Ferguson DJ, Wilcko WM, Wilcko MT. Reaborcion radicular despues del tratamiento orodoncico con o sin corticotomia alveolar. Reb Venezuela Ortho 2002;19:647–653.

4. Nazarov AD, Ferguson DJ, Wilcko WM, Wilcko MT. Improved retention following corticotomy using ABO Objective Grading System [abstract]. J Dent Res. 2004;83, 2644.

5. Wilcko WM, Wilcko MT, Bouquot JE, Ferguson DJ. Rapid orthodontics with alveolar reshaping: two case reports of decrowding. Inter J Perio and Restor Dent. 2001;21(1):9–19.

6. Wilcko WM, Ferguson DJ, Bouquot JE, Wilcko MT. Rapid orthodontic decrowding with alveolar augmentation. Case Report. World J Ortho. 2003;4:197–205.