by Jeremy D. Orchin, DDS, and Andrew M. Orchin, DDS

How to establish and manage an orthodontic/orthognathic surgical practice

More and more adults are seeking orthodontics to improve their health as well as their cosmetic self-image. There is so much emphasis on facial beauty through news and magazine articles and television reality shows that every orthodontist has seen an increase in the number of adults coming from doctor referrals. An important reason that those patients seek treatment is the recognition and diagnosis of skeletal discrepancies. To achieve a stable, functional, and aesthetic result, orthognathic surgery must be considered.

|

| Jeremy D. Orchin, DDS |

|

| Andrew M. Orchin, DDS |

The past 25 years have seen first an increase followed by a decrease in the number of orthognathic surgical cases being diagnosed and treated by orthodontists and surgeons. Recently, more emphasis has been placed on symmetry, proportionality, and aesthetics rather than treating according to static cephalometric numbers or plaster models in occlusion. To treat facial aesthetics and balance, the orthodontist must be willing to spend the time and energy to develop a very specialized practice.

The Team

The first step in building an orthognathic practice is to organize a team anchored by an orthodontist with experience, knowledge, and interest in aesthetic adult treatment. The orthodontist must be willing to spend the required after-office hours in personal consultation with the other specialists involved. Our team meets at least once per month, for several hours, with our surgeon to review pending surgical cases as well as diagnose and plan cases that have not yet started treatment. The surgeon also must have the same interests and dedication. A double degree with emphasis on facial and reconstructive plastic surgery is an important bonus. The team is completed with an ENT that recognizes the relationship of intranasal issues to occlusion and stability. A speech therapist evaluates presurgical speech issues and informs the patient of postsurgical speech problems that may arise. In syndromal surgical cases, a geneticist should be included to rule out any potential systemic issues. Finally, a periodontist, a TMJ specialist, and a restorative dentist are integral members of the team.

Types of Patients

Patients who require a combined orthodontic/orthognathic surgery approach fall into the following categories:

- Mandibular deficiency/maxillary deformity;

- maxillary excess/mandibular deficiency;

- mandibular excess/maxillary deficiency;

- asymmetric mandibular prognathism;

- syndromal orthognathic surgery;

- hemi-facial microsomia;

- postradiation injury/tumor treatment; and

- bilateral cleft lip/palate.

The Treatment Process

The patient should be carefully guided through a treatment process that closely adheres to the following sequences:

- The first step is an initial exam by both the orthodontist and surgeon. If the surgeon sees the patient first, needed photographs are taken and potential surgeries are reviewed. The surgeon also explains why orthodontics is an integral part of the total treatment.

- If the orthodontist sees the patient first, digital diagnostic records are taken by the orthodontist to be viewed online by the surgeon. At this visit, the orthodontist informs the patient that orthognathic surgery is the first and preferred option for treatment. Informed consent is presented with other options, including no treatment. The orthodontist explains the advantages and risks of orthognathic surgery.

- The treatment plan is determined by the orthodontist and the surgeon through personal consultation and a review of all needed diagnostic records (mounted study model, cephalogram, panorex, PA cephalogram, and facial and dental photographs).

- The surgeon has an in-office consultation with the patient, with needed discussion and informed consent about the surgery

- The orthodontist has a consultation with the patient outlining informed consent about the presurgical, postsurgical, retention, and relapse issues.

- The patient undergoes needed restorative and/or periodontal therapy.

- The patient is evaluated by a TMJ specialist, if indicated.

- An ENT evaluates the patient for intranasal issues.

- A speech therapist evaluates the patient.

- The patient and specialists agree on a plan; informed consent is understood and signed.

- Brackets are placed, and presurgical orthodontics are accomplished. If extractions are required, they take place prior to bracket placement. Third molars are not extracted prior to starting orthodontics.

- Presurgical records are taken once leveling and aligning are complete. The surgeon takes the models and facebow; the orthodontist takes the x-rays and photographs.

- The orthodontist and surgeon consult and determine the exact surgery, using mounted models, ceph, pan, and photographs.

- The patient has a consultation with the surgeon, who reviews again all aspects of the surgery as well as hospital stay and recuperation.

- The patient has surgery (including intranasal/extraction of third molars if indicated, liposuction, and genioplasty).

- The orthodontist takes postsurgical records 6 weeks after surgery.

- The patient has final orthodontic detailing, including needed elastic wear.

- The braces are removed, and retainers are placed.

- The orthodontist takes final records.

- Post-treatment consultation with the patient illustrates the positive changes and benefits of treatment.

Impediments to Treatment

Impediments to a favorable result occur when just the occlusion is considered. This is the “dental mind-set,” when we have heard for years to “put your plaster on the table.” This nonsurgical or camouflage approach to achieve a stable occlusion often results in excess orthodontics, multiple extractions, periodontal problems, and/or relapse, with no regard to facial aesthetics.

The minor surgical approach—doing single-jaw surgery when double-jaw surgery is indicated, for example—can result in limited aesthetic improvement, relapse, and often a less than satisfactory occlusion. This “cosmetic mind-set” addresses soft tissue only by tightening the skin or placing chin or cheek implants. It often results in overtightening the skin and creating a “surgical” or “operated” look.

Sample Cases

Case 1 involves mandibular deficiency/maxillary deformity in a young adult.

Improving facial aesthetics requires looking at enhancement versus compromise in correcting vertical length as well as horizontal projection problems. Through our experience, we have found that the ideal is actually toward the side of excessive rather than inadequate movement, as demonstrated by the following case.

This is a 22-year-old female who was referred by the surgeon because she was unhappy with her facial appearance. She believed that she looked much older than she actually was. She presented with a Class II division 1 (Class II left) with severe overbite and overjet. The lower midline was 3 mm left of midsagittal. She had a short anterior vertical dimension with decreased horizontal projection and an edentulous look. Her first visit was for a second opinion: The first orthodontist had presented a plan to do conventional orthodontics with headgear and elastics. She intuitively knew this was not the proper approach to correct her aesthetic concerns.

|

Treatment Protocol

- 7/12/01 Initial Records

- 8/07/01 Brackets Placed

- 3/01/02 Presurgical Records

- 5/23/02 Surgery Le Fort 1: advance /lengthen vertically/rotate clockwise BSSO: advancement Genioplasty: lengthen vertically/advance horizontally

- 8/12/02 Brackets removed

- 11/04/02 Final records after 13 months of active treatment time

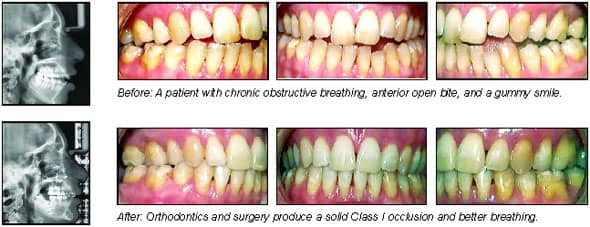

Case 2 was a patient with maxillary excess/mandibular deficiency.

This 30-year-old female was referred by the surgeon for orthodontics in preparation for orthognathic surgery to correct her chronic obstructive nasal breathing and her vertical maxillary excess. She presented with a Class I molar occlusion, an anterior open bite, and a gummy smile. She had undergone previous camouflage orthodontic treatment that included extraction of the four first bicuspids. Dental relapse occurred because the underlying skeletal discrepancies were not addressed. She had upper and lower anterior crowding as well as significant gingival recession. The third molars were all fully erupted.

This type of case has special considerations, such as:

- chronic obstructed nasal breathing (ONB);

- the extent of jaw deformity being dependent on the degree and timing of ONB;

- chronic nasal obstruction;

- a long, flat retrusive face; and

- an anterior open bite;

Preoperation protocol should include an ENT evaluation for deviated septum and enlarged inferior turbinates, as well as an evaluation by a speech therapist.

|

Treatment Protocol

- 10/10/00 Initial exam

- 11/00 to 2/02 Periodontal therapy/ENT/Speech

- 3/15/02 Initial records and brackets placed

- 8/8/02 Presurgical records

- 1/12/02 Surgery Le Forte I in 3 segments, BSSO, genioplasty, extract third molars, septoplasty, reduce inferior turbinates, neck liposuction

- 12/17/02 Postsurgical records

- 7/17/03 Remove brackets/lingual bond lower/positioner

- 11/24/03 Final records (16 months treatment time)

Conclusion

Contemporary orthodontics/orthognathic surgery is predictable and stable when performed by a dedicated team that has the experience and expertise to diagnose and treat all types of dentoskeletal problems, from the simple bilateral split ramus osteotomy to the very complex cases. Treating skeletal discrepancies with orthognathic surgery should be the first option considered, rather than accepting a camouflage result that may not be stable or aesthetically acceptable.

Our team treatment-plans the case to perform all required surgical procedures at one time:

- LeFort I with the following options: one piece or segmental; advance; vertically lengthen or shorten; alter cant of occlusal plane; or expand.

- Bilateral Sagittal split osteotomy: advance; set back; or rotate.

- Genioplasty: advance; reduce; shorten; or lengthen.

- Extract third molars

- Intransal surgery septoplasty; or reduce inferior turbinates.

- Neck liposuction

- Rib graft

- Rigid internal fixation

Doing all the surgical procedures at the same time results in shorter treatment times; satisfied patients; and improved self-image, aesthetics, function, breathing, and speech. Enjoy the satisfaction of being an integral member of a team on the leading edge of contemporary orthodontics and orthognathic surgery. Spend the extra time and energy, and watch your practice grow.

The father-and-son team of Jeremy D. Orchin, DDS, and Andrew M. Orchin, DDS, practice as Orchin Orthodontics in Washington, DC. Their focus is multidisciplinary care with a strong emphasis on orthognathic surgery. They are both Diplomates of the American Board of Orthodontics, and they both lecture nationally and internationally. They can be reached at