Understanding the anatomy, rationale for use, and cephalometric landmarks

By Neal D. Kravitz, DMD, MS, and Shawn L. Miller, DMD, MMedSc

The anterior cranial base is used by orthodontists in cephalometric analysis as a stable reference to measure skeletal growth and the effects of orthodontic treatment. Understanding it is an important component of clinical practice and Board certification. The purpose of this article is to review the fundamentals of the anterior cranial base—its anatomy, rationale for use, and cephalometric landmarks.

Anatomy

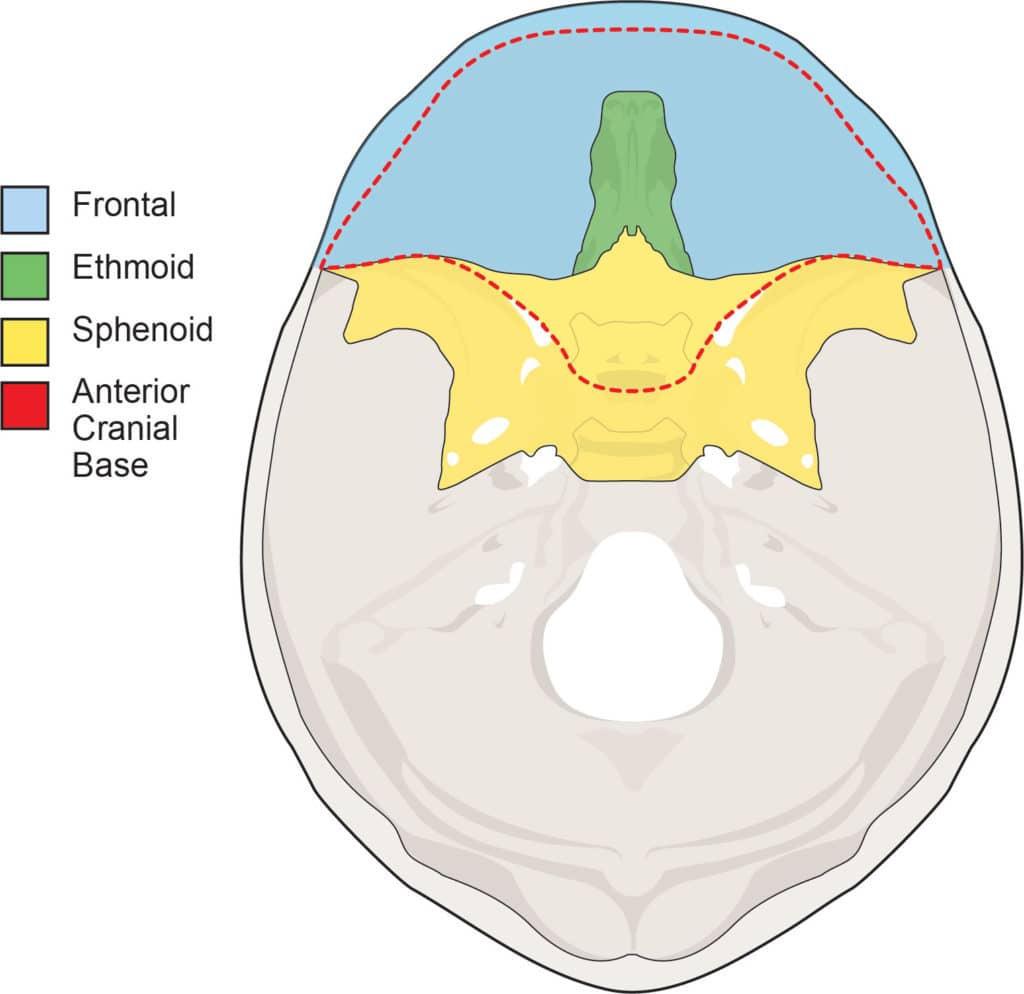

The anterior cranial base is formed by the orbital part of the frontal bone, the cribriform plate of ethmoid bone, and the anterior part of the body and the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone (Figure 1).

The orbital part of the frontal bone forms the roof of the orbit and its cerebral surface supports the frontal lobes of the brain. It is separated by the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, which supports the olfactory bulb. The body of the sphenoid bone includes the sella turcica, which contains the pituitary gland. It is bordered by the anterior clinoid processes and the jugum (planum) of the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone.

Rationale for use

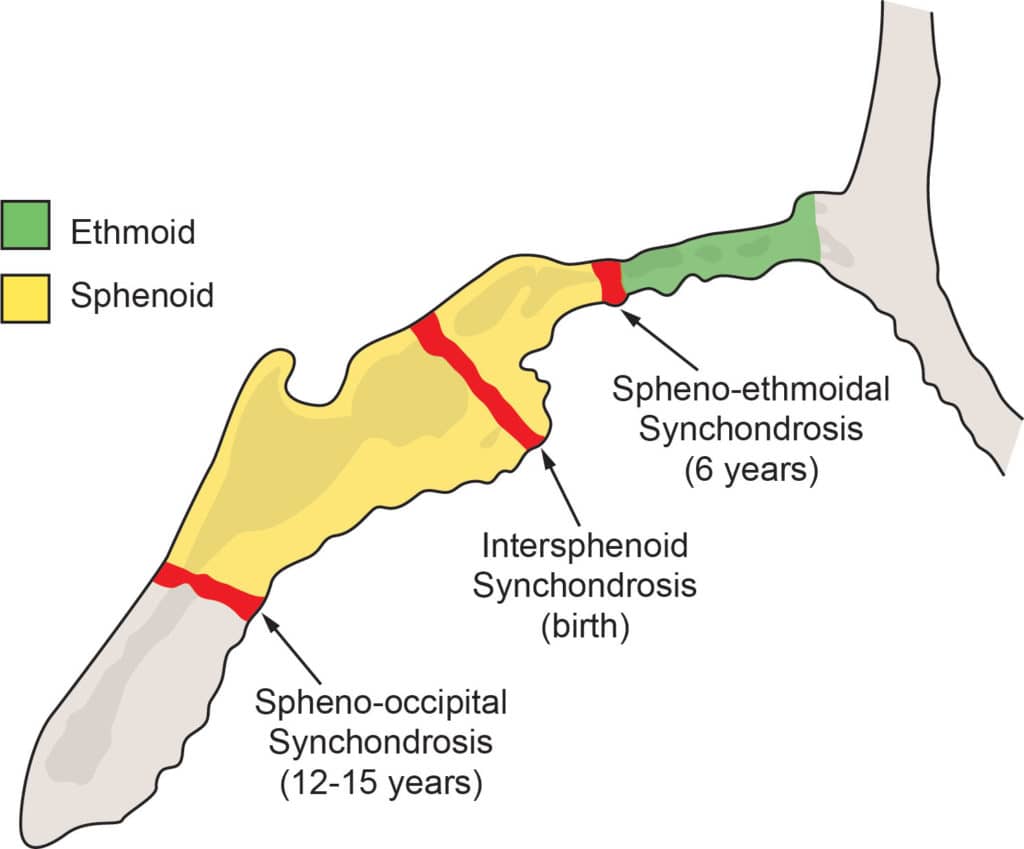

The anterior cranial base is considered a stable craniofacial structure to be used for superimposition, because it completes the majority of its growth before the age of 7. The reason is because its cartilaginous growth center, the spheno-ethmoidal synchondrosis, has ossified by this time (Figure 2). Understandably, the growth curve of the anterior cranial base correlates with its functional matrix—the brain and the face.

This relationship can be seen in Scammon’s curves. Scammon (1930)1 summarized the growth of different tissues in the body into four curves: general, neural, genital, and lymphoid. The neural curve, representing the brain and face, plateaus by age 7. In other words, Scammon’s curves show that the neural tissues grow early and are not affected by pubertal growth.

These results were corroborated by Nanda (1955),2 who analyzed growth curves of the head using cephalograms. The growth of the anterior cranial base was a composite of both neural and facial growth. He concluded that its growth slowed off markedly after age 6 and had a barely perceptible pubertal spurt. The anterior cranial base, therefore, has stabilized before most patients are ready for treatment.

Cephalometric Landmarks

The anterior cranial base is measured cephalometrically as the Sella-Nasion (SN) line. Sella is the midpoint of sella turcica. Nasion is the most anterior point of the frontonasal suture that joins the frontal and nasal bones.

However, neither sella nor nasion is actually a stable landmark.3 Due to remodeling of the posterior of sella turcica during growth, sella is displaced in a backward-downward direction. Likewise, due to apposition in the glabella region during growth, nasion moves in a forward direction. Therefore, other stable anatomical landmarks in the anterior cranial base must also be traced.

These landmarks are based on the longitudinal growth studies by Björk (1955)4 using tantalum implants, and later supported by the histological studies by Melsen (1974).5 They include: (1) the anterior wall of sella turcica, (2) Walker’s Point, (3) the greater wings of the sphenoid, (4) the cribriform plate, (5) the ethmoidal crests, (6) the jugum sphenoidale, and (7) the orbital part of the frontal bone (Figure 3).

Cranial Base Superimposition

Primary landmarks can then be oriented for cranial base superimpositions. The inner contour of the anterior wall of sella turcica and the greater wings of the sphenoid are used for sagittal orientation. Walker’s Point and the cribriform plate or the ethmoidal crests are used for vertical orientation (Figure 4). If these structures are not clear, the jugum sphenoidale and the orbital part of the frontal bone can be used.

The goal of cranial base superimposition is to allow the orthodontist to assess the overall changes of the teeth that occur as a result of skeletal growth or orthodontic treatment. Those interested in reviewing this topic more should watch the video tutorial, 2D Cranial Base Superimposition, provided on the American Board of Orthodontics website, narrated by Buschang.

Conclusion

The anterior cranial base is composed of parts of the frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones. It is used as a stable reference for cephalometric analysis because it exhibits little growth after age 7, as its synchondrosis has ossified. During superimposition, the primary structures for orientation are the anterior wall of sella turcica, the greater wings of the sphenoid, Walker’s Point, and the cribriform plate. OP

References

- Scammon, RE. The measurement of the body in childhood. In Harris, JA, Jackson, CM, Paterson, DG and Scammon, RE, Eds. The Measurement of Man, Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. 1930.

- Nanda, RS. The rates of growth of several facial components measured from serial cephalometric roentgenograms. Am J Orthod. 1955; 41: 658-73.

- Björk, A. Guide to superimposition of profile radiographs by “The Structural Method”. Available from: https://www.angle-society.com/case/guide.pdf.

- Melsen, B. The cranial base: the postnatal development of the cranial base studied histologically on human autopsy materials. Acta Odontol Scand. 1974;32:Suppl.62.

- Björk, A. Cranial base development. Am J Orthod. 1955;41:198–255.

Neal D. Kravitz, DMD, MS, is a Diplomat of the American Board of Orthodontics, member of the Edward Angle Honor Society, and serves on the editorial board for Orthodontic Products. Kravitz is a graduate of Columbia University and received his DMD from the University of Pennsylvania. He is also a prolific writer for numerous journals. Kravitz lectures throughout the country and internationally on treatment planning, clinical and practice management pearls, and ethics.

Shawn L. Miller, DMD, MMedSc, is in private practice in Orange and Aliso Viejo, Calif. He completed his dental degree at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine and his Masters of Medical Sciences degree and orthodontic residency at Harvard University School of Dental Medicine. He lectures on accelerated orthodontic treatment, lingual braces, and interdisciplinary orthodontic treatment.